It’s just another day at a railway station. A man is seated in a coach. His friend is waiting on the platform. The train is about to depart; the engine sends up plumes of smoke and the whistle blows. The friend brings out a book from his bag and gives it to the man, to read during the journey. You will surely like it, he says. What follows is rather dramatic.

"The book was impossible to set aside, once I had begun. It gripped me.” Then, "I could not get any sleep that night.” Sounds like a thriller? No. "I determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book.”

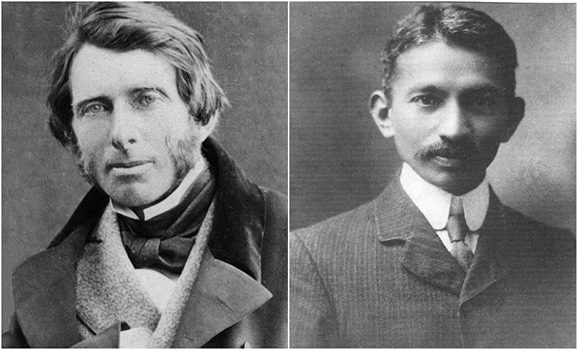

In 1904, between 8-25 June, MK Gandhi travelled from Johannesburg to Durban twice. This event related to one of those two journeys, says An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth: Critical Edition (edited by Tridip Suhrud, published by Penguin in 2018). The friend was Henry Polak, and the book was Unto This Last by John Ruskin, whose 200th birth anniversary is on 8 February 2019.

Gandhi recounts the experience in his autobiography, in a chapter titled ‘The magic spell of a book’, and says this was the book "that brought about an instantaneous and practical transformation in my life”. This was because he "discovered some of my deepest convictions reflected in this great book”.

Gandhi summarised Unto This Last's teachings in these three points:

That the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.

That a lawyer’s work has the same value as the barber’s, inasmuch as all have the same right of earning their livelihood from their work.

That a life of labour, i.e., the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicraftsman, is the life worth living.

The turning point in Gandhi's life is said to be when he was thrown out of the first-class compartment of a train, on racial grounds. Richard Attenborough’s film has contributed to the making of this myth. It is a dramatic scene, yes, but Gandhi continued his journey the next day — and continued to face racial discrimination during the trip too. On reading Ruskin’s book, however, Gandhi would not wait even for a day more ("I arose with the dawn, ready to reduce these principles to practice”). Within a day, he launched plans to set up the Phoenix Settlement, where he would experiment with "a life of labour”. The credit for epiphany should go not to the Pietermaritzburg station, but to another station at the end of the same rail line — Park Station of Johannesburg.

Gandhi at 34 was a novice in spiritual training, and the Phoenix Settlement was not more than an experiment in alternative economics, but it was the prototype for later, more focused experiments like the Tolstoy farm, Satyagraha Ashram in Sabarmati, and Sevagram in Wardha.

In letters, speeches and interviews, the Mahatma repeatedly spoke of the lasting impression the Sage of Coniston made on him.

In 1906, when some locals complained against Indian Opinion (the newspaper Gandhi published) to Lord Elgin, secretary in charge of colonial affairs in the British government, Gandhi wrote in defence was that his publication was "run on Tolstoy’s and Ruskin’s lines”. He summarised Unto This Last in Gujarati as Sarvodaya ('The Welfare of All'), published in nine instalments in Indian Opinion during May-July 1908. The only other work he summarised in Gujarati was Socrates’ Apology (by Plato). Of course, Gandhi put in Gujarati what he read into the book: for example, the first of the four essays in it is titled ‘The Roots of Honour’; Gandhi renders it as ‘The Roots of Truth’.

In 1907, in a letter to Chhaganlal Gandhi, his one-line prescription is: "Do please read Ruskin’s book.” Writing to son Manilal from jail in 1909: "I have been reading Emerson, Ruskin and Mazzini.” Reporting to his readers ‘What I Read in Gaol’, he named "great Ruskin” and "great Thoreau” in whose writings "we can find the doctrine of Satyagraha … All this reading had the effect of confirming my belief in Satyagraha.”

We can better appreciate the formative influence of Unto This Last on Gandhi’s thought when we read the concluding chapter of Sarvodaya – applying Ruskin’s message to the Indian condition – and then read the opening pages of his all-too-crucial Hind Swaraj: there is a seamless continuity. Hind Swaraj acknowledges this by naming two of Ruskin’s works in the appendix under the title ‘Some Authorities’.

If we turn to the other, equally important text by Gandhi, the autobiography quoted at length above, he forms a personal pantheon:

"Three moderns have left a deep impression on my life and captivated me: Raychandbhai [spiritual leader Srimad Rajchandra] by his living contact; Tolstoy by his book, The Kingdom of God Is Within You; and Ruskin by his Unto This Last.”

This — a listicle in today’s language — Gandhi was to repeat on many occasions: in his preface to a commemorative volume on Srimad Rajchandra, in a short tribute to him in The Modern Review, in his centennial tribute to Tolstoy in a meeting held at Sabarmati Ashram in 1928. In a letter to Premabehn Kantak, a teacher in the Sabarmati Ashram, in 1931, Gandhi wrote: " ‘Hero’ means one worthy of reverence, a god, so to say. … The persons who have influenced my life as a whole in a general way are Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau and Raychandbhai. Perhaps I should drop Thoreau from this list.” A year later, to Mirabehn he wrote about reading Ruskin’s Fors Clavigera, "a deeply human document”, and found the author to be "dreadfully in earnest”.

In 1931, when the editor of the British magazine Spectator, Evelyn Wrench asked him — rather knowingly — if any book every affected him supremely or if there was any turning point in his life, Gandhi readily rephrased the portion quoted above from the autobiography, and claimed it was Unto This Last which "made me decide to change my whole outward life”.

More than influencing his own life, Gandhi dreamt of Ruskinian thoughts influencing soon-to-be-independent India. In July 1946, Vaikunthlal Mehta, finance and village industries minister of Bombay state, organised a conference of state industries ministers in Pune. Addressing them, Gandhi once again fondly recalled the magical spell of that book, and told the people who were going to chart the industrial future of a free India soon:

"I saw clearly that if mankind was to progress and to realise the ideal of equality and brotherhood, it must adopt and act on the principle of Unto This Last; it must take along with it even the dumb and the lame… That is not my picture of independence in which there is no room for the weakest. That requires that we must utilise all available human labour before we entertain the idea of employing mechanical power.”

* * *

John Ruskin [8 February 1819-20 January 1900] was recognised, right from his early 20s, as a leading art critic and literary essayist of England. Inspired by the Bible, he brought a moral viewpoint to art criticism. A young man named Marcel Proust was so enamoured by Ruskin’s essays that even with only a limited knowledge of English, he translated two of his books into French. This apprenticeship served him well when he wrote one of the masterpieces of 20th century fiction, In Search of Lost Time.

Ruskin saw no difference between artists and craftsmen. In recent years, some people are turning to handicrafts as a counter to the culture and ideology of assembly-line mass production, and Ruskin is the patron saint of this movement.

But the Ruskin that influenced Gandhi was the critic of the newly emerging discipline of ‘political economy’ that took market as a God-given reality. Opposing thinkers ranging from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill, Ruskin argued that the laws of economics are not like the laws of physics, and we must reset them in accordance with our moral compass. This ideology he captured in the biblical Parable of the Vineyard, from where comes the title Unto This Last: equal pay to all workers, regardless of who could work more or less. There are many who trace the origins of the welfare state — state-provided social security that is the norm even in capitalist countries — to Ruskin.