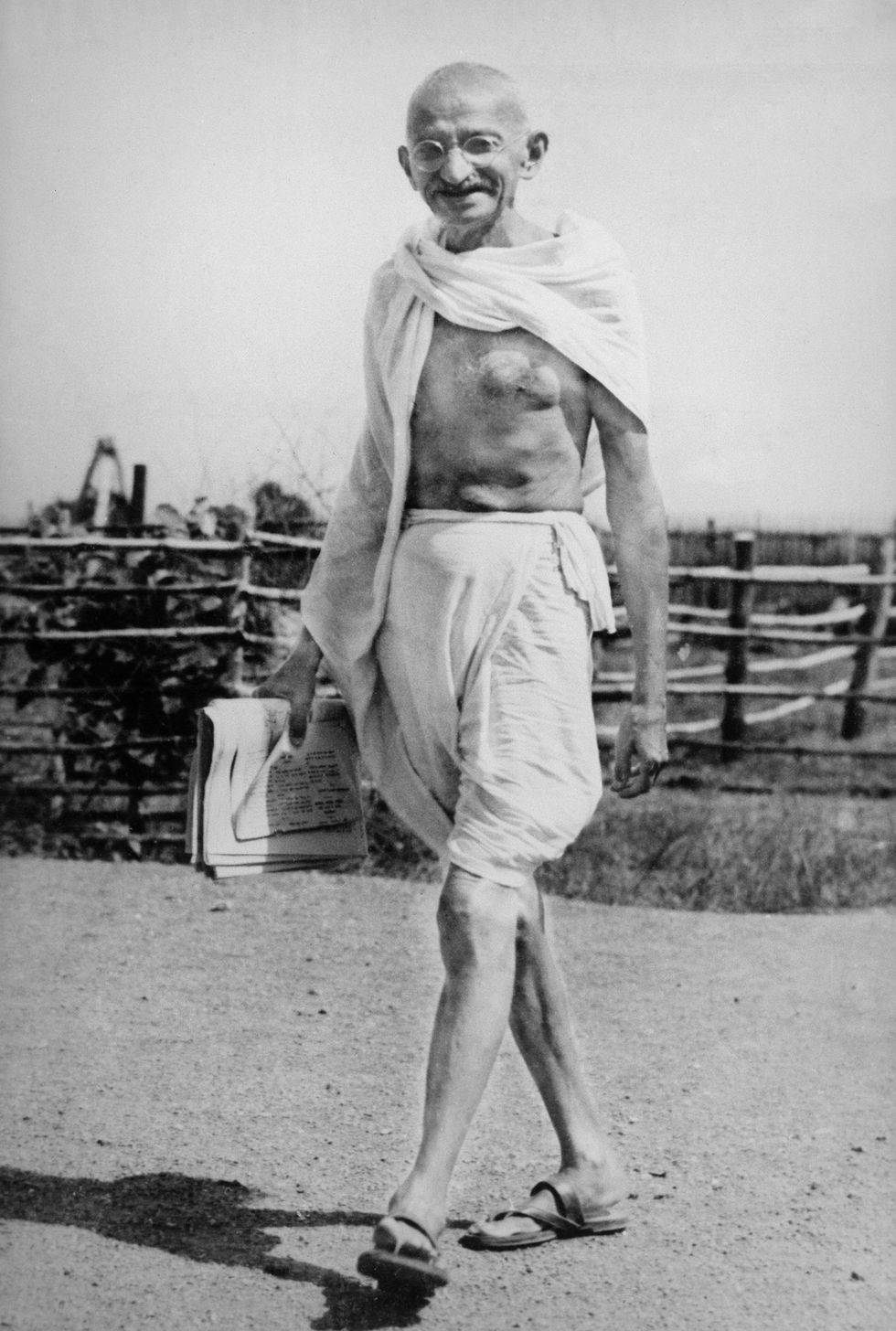

M.K. Gandhi as a Author |

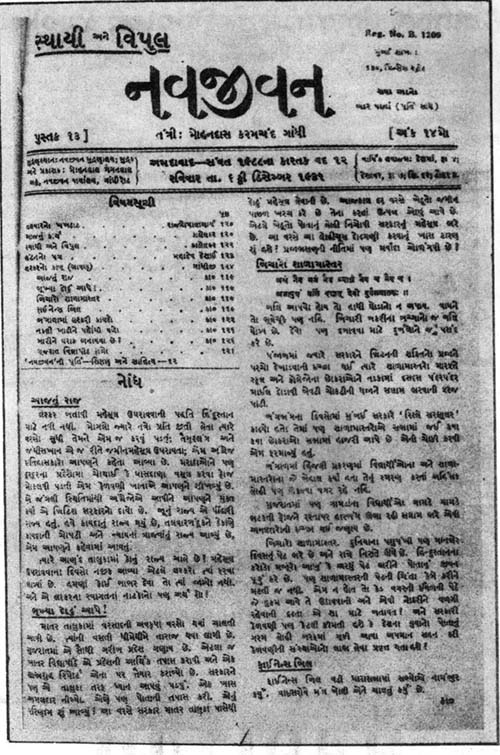

Gandhi became a regular reader of newspapers after reaching England at the, age of 19. As a school student in India, he did not read, them. He was very shy and could not speak in a gathering. At 21, he first wrote nine articles for The Vegetarian an English weekly, on vegetarianism, Indian food habits, customs and religious festivals. His earliest writings show his capacity for expressing any idea in simple direct language. After a gap of two years, Gandhi again took to journalism. From that time onwards his pen knew no rest till the end of his life. He never wrote anything only for creating an impression and carefully avoided exaggeration. His aim was to serve truth, to educate people and to be useful to his country. On the third day of his arrival in South Africa he was insulted in a court of law. He published an account of this incident in a local paper and gained publicity overnight. At the age of 35, he took charge of lndian Opinion and through it he guided and unified the Indians in South Africa. A Gujarati edition of this weekly was simultaneously printed at Phoenix. A series of articles on dietetics appeared in the Gujarati Indian Opinion, also the life sketches of great men and women. Every issue of these weeklies contained articles by Gandhi. There was an editor, but Gandhi bore the whole burden. He wanted to educate the public opinion, to remove causes of misunderstanding between the whites and the Indians and to point out the drawbacks of his countrymen. He poured out his soul in the columns of Indian Opinion and published detailed account of the satyagraha struggle carried on in South Africa. From his writings overseas readers could form a true picture of the happenings in South Africa. Among the distinguished readers were Gokhale in India, Dadabhai Naoroji in England and Tolstoy in Russia. For ten years Gandhi worked hard for this weekly. He got two hundred journals per week in exchange of Indian Opinion, read each one of them carefully and reproduced such news as might benefit the readers of Indian Opinion. Gandhi knew newspapers could become powerful medium for spreading ideas. He was a successful journalist but never intended to make a living from journalism. In his opinion the aim of journalism was service: "Journalism should never be prostituted for selfish ends or for the sake of carrying a livelihood. And whatever happens to the editors or the journal, it should express views of the country irrespective of consequences. They will have to strike a different line of policy if they wanted to penetrate into the hearts of the masses." When he took charge of Indian Opinion, it was a losing concern and had a circulation of four hundred. For some months Gandhi had to contribute Rs. 1,200 per month to keep it going. Altogether he incurred a personal loss of Rs. 26,000. In spite of this heavy loss, he later decided to leave out all advertisements in order to devote more space for his ideas. He knew that he would not be able to serve truth and remain independent if he accepted advertisements. He never cared to increase the sale of his journals through improper means, nor to compete-with other newspapers. In India too, he stuck to this tradition and for 30 years published his journals :without any advertisement. He suggested that for each province, there should be only one advertising medium printing decent descriptions of things useful to the people. After accepting the editorship of Young India, he was keen on conducting a Gujarati paper because a vernacular paper was a felt want. Editing a newspaper in English was no joy to him. He brought out Navajivan, the Hindi and Gujarati version of Young India, and contributed many articles regularly. He was proud to say that many readers of Navajivan were the farmers and workers who really made India.

Under heavy pressure of work he had to write a lot and had to work late at night or in the early hours of the morning. He often wrote on a running train. Some of his famous statements or editorials bore the mark "on the train". When his right hand got tired, he wrote with the left. His left-hand writing was more legible. Even while convalescing he wrote three to four articles every week. In India he did not run any paper on loss. Both his English and Indian language papers reached a circulation of 40,000. When he was jailed, the circulation dropped down to 3,000. After his release from the first imprisonment in India, a new feature of the weeklies was the publication of his autobiography in a serial form. It continued for three years and created world-wide interest. He allowed almost all the Indian papers to reproduce his life-story. While in jail, he started another weekly Harijan. Like Young India this too was priced one anna. It was mainly devoted to serve the untouchables. For years it did not contain any article on politics. It was first brought out in Hindi. Gandhi was permitted to write thrice a week from jail. Regarding the proposal for an English edition, he wrote to a friend: "I would warn you against issuing the English edition unless it is properly got up, contains readable material and translations are accurate. It would be much better to be satisfied with the Hindi edition only than to have an indifferently edited English weekly. I shall not handle the paper except to make it self-supporting." He proposed to bring out 10,000 copies in the beginning and give it a trial of three months. In two months' time, it became self-supporting. Later it became a very popular views-paper. People read it not for amusement but for instructions. It was published in English, Hindi, Urdu, Tamil, Telugu, Ooriya, Marathi, Gujarati, Kannada and Bengalee. Gandhi wrote articles in Hindi, Urdu, Gujarati and English. Gandhi journals never had any sensational topics. He untiringly wrote on constructive work, satyagraha, nonviolence, diet, nature-cure, Hindu-Muslim unity, untouchability, spinning, khadi, swadeshi, village industries and prohibition. He stressed the need of re-orientation of education and food habits and was a severe critic of national defects. He was a hard task-master. His secretary, Mahadev Desai, had to seek shelter in the lavatory from the crowded railway compartment and complete his work in time. Gandhi's assistants had to know all corresponding railway timings and postal clearance hours for a timely despatch of written matter for publication. Once the train carrying Gandhi and his articles written on it was running late and there was no time for sending them by post. The English articles were sent by a messenger and were printed in Bombay instead of his own press at Ahmedabad. The issue was brought out in time. Gandhi was first jailed in India for his bold articles printed in Young India. He never submitted to any gagging order issued by the Government. When he was not allowed to express his deepest thoughts, he stopped writing. He was confident that he could any-day persuade his readers to copy his editorials for him and circulate the news. He knew his paper could be suppressed but not its message, so long as he lived. By not caring for the aid of printing-room and compositor's stick, the hand-written paper, he assured, could be a heroic remedy for heroic times. Gandhi published an unregistered weekly Satyagraha in 1919, defying the Government orders. This one-sheet weekly was sold for one pice. Himself being a journalist of many years standing, he spoke with authority on the traditions of good journalism: "The newspaperman has become a walking plague. Newspapers are fast becoming the people's Bible, Koran and Gita rolled in one. A newspaper predicts that riots are coming and all the sticks and knives in Delhi have been sold out. A journalist's duty is to teach people to be brave, not to instill fear into them." |