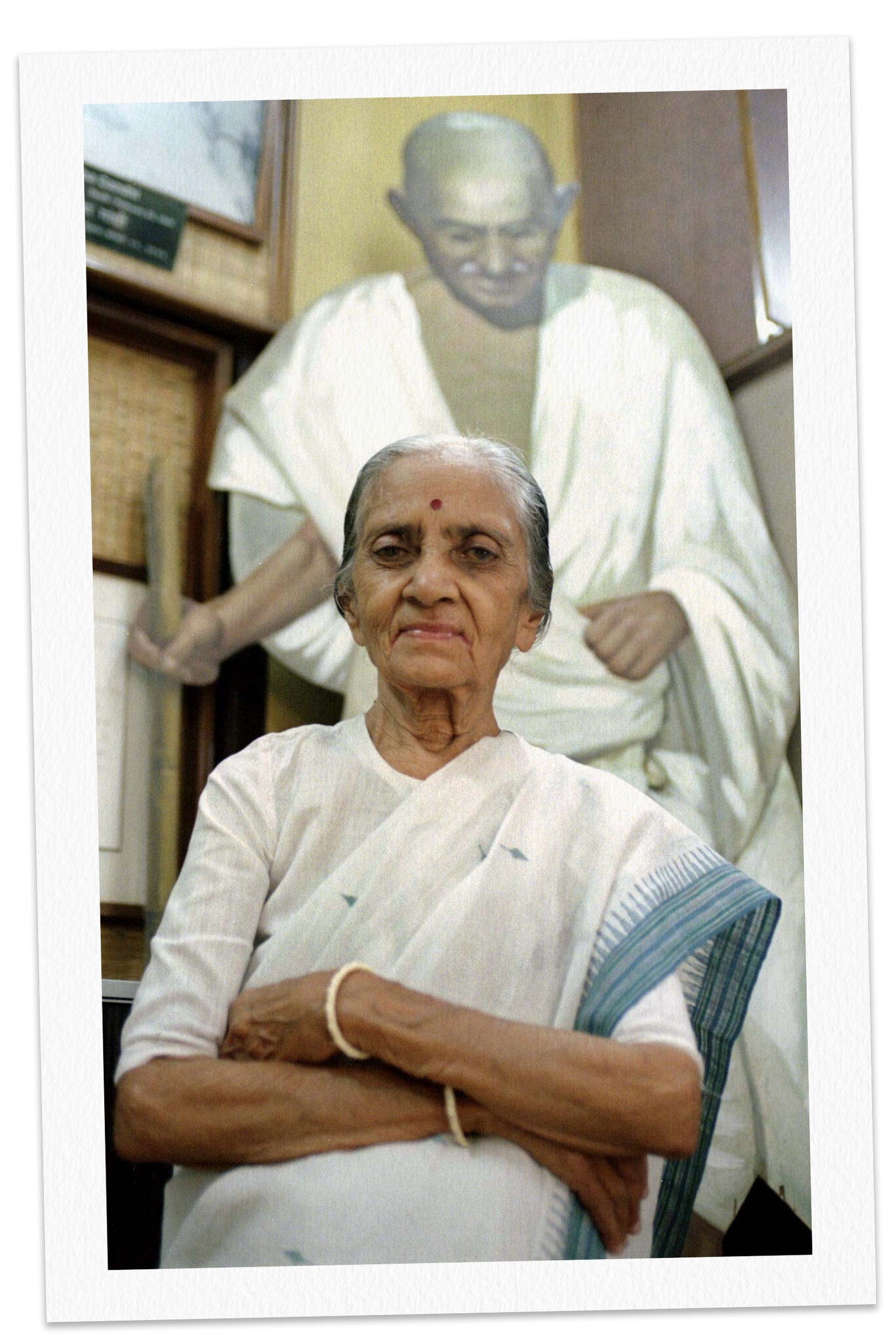

Usha Mehta, Freedom Fighter against British Rule in IndiaAt 22, she helped establish the underground station Congress Radio, which amplified Mahatma Gandhi's message of rebellion. |

- By Geneva Abdul When Mahatma Gandhi gave his famous "Do or Die" speech on August 8, 1942, galvanizing Indians to demand the end of British rule, Usha Mehta heeded the call. With the help of other activists, Mehta, who was 22 at the time, secured a ghost transmitter and started an underground radio station to amplify Gandhi's message. "When the press is gagged and all news banned, a transmitter certainly helps a good deal in furnishing the public with the facts of the happenings and in spreading the message of rebellion," Mehta recalled in a 1969 interview. Gandhi had called for the start of a mass civil disobedience movement, the Quit India campaign, but he was quickly arrested by the British, as were the Congress leaders who were supporting him. On August 14, Mehta and her colleagues, broadcasting from a secret location, went live. "This is Congress Radio calling on 42.34 meters from somewhere in India," she said from behind the microphone, referring to their wavelength. Mehta and others relayed news, patriotic speeches and appeals directed at the people she called "workers in the struggle" — students, lawyers and police officers. She passed along information from the All India Congress Committee and delivered messages from across the country. The broadcasts were originally once a day but quickly transitioned to twice a day: once in the morning and once in the evening, in both English and Hindustani. Mehta, who at the time was a political science student at Wilson College in Bombay (now Mumbai), said she had read about how radio stations aided movements in the past. The broadcasts, she realized, could reach beyond India to gain the attention of other countries. "Our perusal of the history of the past campaigns had convinced us that a transmitter of our own was perhaps one of the most important requirements for the success of the movement," she said in 1969. Mehta and her collaborators broke the news of a Japanese air raid on a British armory at Chittagong, a port city that is now part of Bangladesh. They also reported on the Jamshedpur Strike, as labor workers from the Tata Iron and Steel Company, the largest integrated steel mill in the British Empire, went on strike for 13 days in support of the Quit India movement and demanded that a national government be formed. And they told the nation about the deadly riots in Ashti and Chimur, as the police opened fire on people protesting the arrests of Congress leaders. As the military was sent in to thwart the uprising, accounts of atrocities against the villagers surfaced. "When the newspapers dared not touch upon these subjects under the prevailing conditions, it was only the Congress Radio which could defy the orders and tell the people what actually was happening," Mehta said. Mehta and her colleagues were regularly chased by a police van, forcing them to shift from place to place to hide their location. To avoid further risk, they had a recording station separate from the broadcast station and for a period aired messages across two transmitters. "So far we were conducting movements, but now we are conducting a revolution," Ram Manohar Lohia, a founder of the Congress Socialist Party, said in one broadcast, adding, "Our hatred is for an administration which seeks to perpetuate human injustice." After the official All India Radio — which other activists referred to as "Anti-India Radio" — jammed their broadcasts, Mehta and her crew persistently tried to retaliate. But their luck fell short on November 12, 1942, when they were caught after a technician betrayed them by revealing their location. "When finally the government traced them down, the police were knocking on the door where they were running this underground radio," her nephew Ketan Mehta, a prominent Bollywood filmmaker, said in a video call from Mumbai. "And she asked all the others to leave, but she continued to broadcast until they broke down the door." More than 50 officers stormed through the three bolted doors. Mehta and another activist were arrested; two others were caught in the following days. After a prolonged investigation, time in solitary confinement and a five-week trial, Mehta was jailed until March 1946. "I came back from jail a happy and, to an extent, a proud person, because I had the satisfaction of carrying out Bapu's message, ‘Do or die,'" she said, using a term of respect for Gandhi that means "father," "and of having contributed my humble might to the cause of freedom." Usha Mehta was born on March 25, 1920, in Saras, a village in the western state of Gujarat, to Gheliben Mehta, a homemaker, and Hariprasad Mehta, a district-level judge under the British Raj. Throughout her upbringing, members of Usha's family were involved in India's independence struggle. After her father retired in 1930, the family relocated to Bombay. To her father's displeasure, Mehta later joined the movement, distributing bulletins and selling salt in small packets as part of Gandhi's "salt march" to protest a colonial law allowing the government to regulate and monopolize salt. Mehta never married or had children. When India finally achieved independence in 1947, the British drew a dividing line that became the border between India and Pakistan, sending the region into chaos that resulted in mass bloodshed as more than 10 million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs sought to find their place in what would become history's largest migration. Mehta was torn. "In a way I was very happy, but sad at the same time because of partition," she was quoted as saying in the book "Freedom Fighters Remember" (1997). "It was an independent India but a divided India." Later in life Mehta wrote the script for a documentary on Gandhi that was produced by one of her colleagues at the radio station. She earned a Ph.D. in Gandhian thought at the University of Bombay, where she taught political science and ran the politics department. She also taught at Wilson College for 30 years. She was president of the Gandhi Peace Foundation and in 1998 received one of India's highest civilian honors, the Padma Vibhushan. She lived a simple, even frugal life. She rode the bus instead of driving a car and dressed in khadis, a handwoven garment that became a symbol of defiance in Gandhi's time. She often subsisted on only tea and bread. She woke at 4 a.m. each day and worked late into the evening. She died on Aug. 11, 2000. She was 80. One morning shortly after Congress Radio's first broadcast in 1942, Mehta's uncle brought her a note from Ram Manohar Lohia, the Congress Socialist Party founder. "I do not know you personally," the note read, "but I admire your courage and enthusiasm and your desire to contribute your might to the sacrificial fire that has been lit by Mahatma Gandhi." Courtesy: The New York Times, dt. 13.05.2021. |