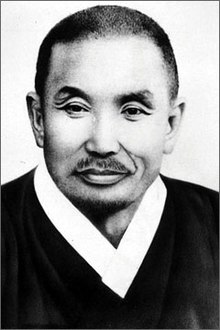

Cho Man-sik - Korean GandhiFollower of Gandhian ideologies of Ahimsa and Swadeshi |

- By Ram PonnuCho Man-sik, a national peaceful activist during the Korean independence movement, was known as the Gandhi of Korea. He was inspired by Gandhian principle of non-violence and swadeshi and followed him as the model for his independence movement. He played a prominent part in the self-strengthening movement and anti-Japanese movement in Korea. He was the most revered and established political leader within the northern region of the Korean peninsula. He served time in prison for leading the independence movement in Pyongyang during the March 1st Independence Movement. He was a passionate Christian too. Cho was ostensibly an independence activist who began his work before there was a North or a South Korea. Early Life

Cho Man-sik was born as the son of a medium owner-cultivator, Cho Kyung-hak and Kim Kyung-kun in a relatively poor and strongly Christian village in Gangseo, South Pyeongan Province, in what is now North Korea on 1 February 1883. In his early life, Cho was somewhat of a roustabout, drinking and fighting. In 1904 he gave up that life and went to a mission school. He was raised and educated in a traditional Confucian style but later converted to Protestantism and became an elder.1 In June 1908 Cho moved to Japan to study law in Tokyo at Meiji University and graduated in 1913. Similar to Gandhi, Cho Man Sik travelled to a different country to study law. While Gandhi travelled to London, Britain to study law, Cho Man-sik travelled to Tokyo, Japan to study law. It was while studying in Japan that Cho Man-sik read about, and was impressed by, the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi about non-violent resistance to colonial oppression. Although a skilled fighter in his youth, Cho Man-sik has oft been likened to Gandhi for his unwavering commitment to non-violence during his both principled and strategic resistance to Japanese imperialism. Cho later used the ideologies of non-violence and swadeshi of Gandhi to resist the Japanese colonial rule over Korea. He was well read, is reported to be an admirer of Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (another famous proponent of non-violence) and esteemed Jesus Christ as his master. Upon returning to Korea, he became involved in teaching, which he was as an important way of strengthening the national character and ultimately preparing the nation for throwing off the yoke of Japanese rule. Cho started his teaching career at Osan School, later becoming its principal. During this time he lived in the school dormitory, got up and exercised with the students and even cleaned the facilities, as well as teaching them Bible, English and law. During this time, Cho Man-sik was instrumental in several organizations promoting the establishment of schools and universities, as well as raising people’s awareness of Korean independence.2 Cho stood at the forefront of the formidable battle for Korean dignity and self-determination. Non-violenceBefore Cho believed in Jesus he was a fighter and drunkard; however after he came to know God he was totally transformed, avoiding sinful places and entertainments. He chose the difficult way of the cross. He did not condemn others but instead obeyed what God asked him to do.3 The Korean peninsula was “annexed” to imperial Japan in 1910 and, despite much armed resistance, Koreans experienced a decade of minimal rights under a brutal colonial regime. He paved the way for the proclamation of the Declaration of Independence by the Korean Youth Independence Corps in Tokyo on Feb. 8, 1919, and played a crucial role in behind-the-scenes preparations relevant to the March First Movement, for which he was imprisoned by the Japanese colonial administration.4 Cho Man-sik was forced to resign as school principal due to his involvement in the nation-wide March First Movement.5 The name refers to an event that occurred on March 1, 1919, hence the movement's name, literally meaning "Three-One Movement" or "March First Movement" in Korean. It was the first nationwide nationalist movement in Korea. It is also called Samil Independence Movement, series of demonstrations for Korean national independence from Japan that began on March 1, 1919, in the Korean capital city of Seoul and soon spread throughout the country. Before the Japanese finally suppressed the movement 12 months later, approximately 2,000,000 Koreans had participated in the more than 1,500 demonstrations. About 7,000 people were killed by the Japanese police and soldiers, and 16,000 were wounded; 715 private houses, 47 churches, and 2 school buildings were destroyed by fire. Approximately 46,000 people were arrested, of whom some 10,000 were tried and convicted. March First Movement6 for which he had been imprisoned for ten months, along with tens of thousands of other Koreans. After his release, he dedicated himself to non-violent resistance to the Japanese occupation. Cho’s strong nonviolence resistance was what gained respect even from critics. Cho became well-known in Pyongyang, North Korea because of his popular method of resistance, non-violence. Cho has adopted Gandhi’s belief of nonviolent resistance to fight against the Japanese colonial rule over Korea.7 Cho and Gandhi have many similarities and differences that set them apart. Korean Products Promotion SocietyThe Korean economy was a colonial economy: its determining features were controlled by and for the Japanese while Koreans supplied relatively under-paid services and labour. Without political powers, the Koreans could do little about inequities or the export of food and new materials to Japan. But one avenue did appear to be open in Cho Man-sik's view: Koreans could refuse to spend the wealth that remained to them on imported daily necessities and instead patronize such goods as Koreans produced or were able to produce.8 The Koreans admired Gandhi for his sagacity in pointing out the way towards the eternal welfare and happiness of the Indian people and emphasised the ‘necessity of devising a means of self-production’ in Korea as well.9 Cho and Gandhi held similar views, and Cho was influenced through many of Gandhi’s actions. Gandhi’s idea of self-reliance sparked Cho’s idea of establishing the Korean Products Promotion Society. In July 1922, Cho recruited support from among Christian youth and from colleagues Han Kuin-jo, Kim Kwang-su and O Yun-son, proclaimed the formation of the Society and established its headquarters in the P'yongyang Y.M.C.A. offices. The society encouraged the use of native products. It was the largest and most explicit example of this nationalism and as such engendered considerable thought and debate among the Koreans. Cho described its purpose: ‘The present indigence among Koreans is due to mindless contempt of and failure to cherish their own goods. So without realizing it, Koreans are suffering under foreign economic invasion. Beginning with trivial daily merchandise, Japan's capitalistic economic invasion has now ravished our very centre. The way to block this invasion is to increase production of native foods and to develop and raise products to a high level of excellence. These goods must constantly be patronized in order to promote further production’.10 As all types of people from regional personalities to failed examinees and distressed labourers made their pilgrimage to visit Cho, he became something of a symbol of ‘new Korea.' In his blending of traditional commoner's values with the practical elements of the Western religious and scientific outlook, Cho Man-sik was representative of a new approach to Korean national problems which had its roots in the first generation of Christian nationalism of the 1890s. In particular, Cho's practice of influencing the nation through personal moral example rather than political or social authority gained popular support. Cho advocated the Buy Korean Products Movement and the establishment of nationwide consumer co-operatives. Cho intended the Society to be a national movement supported by all religious organizations and social groups, particularly ordinary Koreans. Due to the Korean Products Promotion Society, his strong non-violent resistance, and leading by example rather than political or social authority, Cho gained respect even from critics, and earned him the title “Gandhi of Korea” because of his insistence on a nonviolent path to Korean independence and promotion of native economic production- both inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s nationalist movement in India.11 He led the movement for economic nationalism urging people to buy Korean rather than imported goods. He advocated the people, ‘Sticking to Korean-made products will save the nation’s economy’. Like Gandhi, Cho started to promote the manufacturing of one’s own products rather than purchasing Japanese products. Swadeshi brought together women, children, and people of no status to spin cloth together. Lee Chong-sik observes as follows: In the years ahead the ideas and ideals of Gandhi gained so much momentum in Korea that many organizations emphasising self-production mushroomed and Matsumori Matsumara, Head of the Bureau of Industry of the Korean Governor-General, reported that many Japanese felt forced to close their businesses and farms because of the anti-Japanese sentiments.12 While Gandhi wore pieces of clothing, Cho gave up the western clothing and wore the Korean traditional dress, the hanbok, for his whole life, emphasized that using Korean made products are the short-cut to loving the country.13 Even Cho’s name cards were printed on homemade paper as ‘a symbol of his patronage of Korean products’. He led social movements by organizing the Association to Promote the Use of Joseon Products. He lived like a peasant. One of Cho’s famous quotes during the times of Japan’s colonization was addressed to Koreans who were in favour of better quality imported goods than their home goods. Kenneth Wells says that Cho’s living quarters in Pyongyang were “like a peasant‘s for frugality,” as recalled by an acquaintance. He was respected even by those who disagreed with him due to his “practice of influencing the nation through personal moral example,” fusing “traditional commoner’s values with the practical elements of the Western religious and scientific outlook.”14 One main difference between Gandhi and Cho was that Cho was Presbyterian while Gandhi was Hindu. While Gandhi is well-known to many, Cho remains well-known to mostly the Christian community where he served as a Presbyterian elder. Another difference between both renowned figures was that Cho was less mentioned than other independence activists during his time, while Gandhi was heavily garnering people’s attention. During the Japanese colonization, Koreans respected An Chang Ho or Kim Gu more, both who were activists using violent measures. Cho also became involved in the Korean language press, spending a year as the chief executive at the Chosun Ilbo newspaper, then in dire straits.15 Democratic Party of KoreaOn 3 November 1945, Cho formed his own political party, called the Chosun Democratic Party to represent Koreans in Pyongyang and the north seeking an independent Korea under a democratic system, sought since the beginning of the 20th Century. At the beginning it was intended to turn into an authentic political organization of the nationalist right with the aim to bring about a democratic society after Japanese occupation.it had a strong membership of 5,00,000.16 The Soviets however, did not approve of the Democratic Party of Korea and thus under socialist pressure, Choi Yong-kun was elected the first deputy chairman of the party. Choi Yong-kun was a guerrilla soldier who served in the 88th brigade of the Soviet Union, and was a friend of Kim Il-sung. The party was therefore influenced by Soviet ideals from the beginning. He established the Christian party and after Korea’s liberation from Japan, Russia realized he was so popular that it would have been virtually impossible not to have him lead the government of the five provinces that would soon constitute North Korea. ImprisonmentThe Moscow Conference of 1945 between the victorious Allies discussed the statehood of Korea, proposing a four-power trusteeship for a period of five years, after which Korea would become an independent state. For Cho, this would result in excessive foreign, and particularly communist, influence over his country, and he refused to co-operate. On 1 January 1946, Andrey Alekseyevich Romanenko, a Soviet leader, met with Cho and tried to persuade him to sign support of the trusteeship. Cho however, refused to sign support. After Soviet leaders realized that they could not persuade Cho to endorse Soviet trusteeship, they lost all remaining hope of Cho becoming a prominent North Korean leader reflecting Soviet ideals. On 5 January 1946, Cho was arrested for opposing Soviet policies, and a purge of the Chosun Democratic Party soon followed, making it a leaderless entity following the regime’s orders by Soviet Red Army soldiers and detained in P’yongyang's Koryo Hotel. By the end of 1946, the Soviet authorities and their Korean Communist clients had eliminated practically all possible political and religious opposition. Suppression of the Presbyterian and Methodist churches founded by American Christians followed.17 For some time he was kept under comfortable conditions at the Koryo Hotel, from which position he continued to vocally oppose the communists. He stood in the 1948 vice-presidency election, but by then the Communist influence in the country's affairs was too strong, and he was unsuccessful, receiving only 10 votes from the National Assembly. Cho was later transferred to a prison in Pyongyang, where confirmed reports of him end. He was murdered in obscurity amidst the fog of war; nevertheless, his life and legacy continue to speak volumes to Korea‘s increasingly perilous state of affairs.18 He is generally believed to have been executed along with other political prisoners during the early days of the Korean War, possibly in October 1950. Cho Man-sik is remembered primarily for the work he did in two phases of his life: the struggle against Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) and the battle against Korea’s division and for freedom from Soviet-backed Communist rule (1945-50). His spirit for independence was so strong that he left a will, saying, “When I die, please draw two eyes on my grave stone. I am determined to see Japan collapse even after my death.” He is praised for living only for the independence of Korea and for the people of Korea. He received absolute love and respect from colleagues in both North Koreans and Vietnam, and members of the communist party also thought highly of Cho’s personality.19 Cho was a great man who sacrificed his life for his people as he trusted and followed the way of Christ. Cho had led nationalist activism in Korea for over three decades, influenced by Gandhian principles of non-violent resistance and economic self-sufficiency. References:

Ram Ponnu Principal (Retd.), Kamarajar Govts. Arts College, Surandai, Tirunelveli Dist., Tamil Nadu. Email: eraponnu@gmail.com. |