HAM SOK-HON: The Korean Gandhi |

- Prof Dr Ram Ponnu*"I am a man who has been 'kicked' by God, just as a boy kicks a ball in the direction he wants it to go. I have been driven and led by Him." - Ham Sok-hon

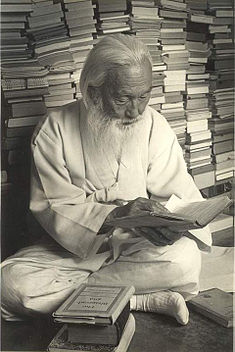

Ham Sok-hon (courtesy: Wikipedia) Ham Sok-hon (13 March 1901 – 4 February 1989) was a civil rights activist when Korea was ruled by dictatorial regimes. He was a notable figure in the Religious Society of Friends (Quaker) movement in Korea, who was influenced by Mahatma Gandhi. His commitment to non-violence earned him the name, ‘the Gandhi of Korea.’ He sought to affirm the identity of Koreans at a time when Korea had fallen prey to Japanese imperialism. Ham believed that discovering one’s identity, especially as a colonised nation, was extremely important as it also determined one’s destiny. Without knowing who you are, it is complicated to know what to do. However, as a maverick thinker,1 he tried his best to merge diverse religions and ideologies. He was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by American Quaker Friends in 1979 and 1985. Although he passed away nearly three decades ago, his legacy still inspires a considerable number of civil rights activists and liberal thinkers in Korea today. Early LifeHam was born to a rural herbal doctor in a small fishing village in P’yongyang province in the extreme northwest corner of North Korea on 13 March 1901. He was brought up as a Presbyterian Christian. In his childhood, Korea was a state of political and economic bankruptcy. The Korean society was filled with ignorance, superstition and corruption, and the people abandoned themselves to despair. With the advent of Christianity in his village, he had the opportunity to study New Education from early childhood. He joined a missionary school of Deok-il Elementary School. Ham Sok-hon said: ‘If we had not received such Christian education in the critical period of national destruction, the conscience of our society surely would have collapsed’.2 During his middle school days he participated in the March 1st Movement, literally meaning "Three-One Movement"3. and he was forced to stop his studies and returned to his native village. In 1921 he joined Osan School to continue his studies. There he learned the teachings of Lao-tzu. In 1923 he left for Tokyo to pursue his higher education. He entered a period of great agony due to a great earthquake in Japan and the subsequent massacre of the Korean people. In 1924 he joined the College of Education. There his class-mate Kim Kyo-shin introduced him to a Bible study group, led by the famous Uchimura Kanzō. From this time he began to attend his Non-church Movement, an indigenous Japanese Christian movement which was founded by Uchimura Kanzō in 1901. Its unique feature was its complete lack of form and ritual, its simplicity of worship, and its emphasis on strict orthodox faith stressing atonement through the Cross and on Bible study.4 Plea for the revival of rural societyUpon graduation from the College of Education, he returned to Korea and became a history teacher at Osan School for ten years. Frustrated by the impossibility of teaching what he described as ‘a series of humiliations, disasters and failures’, he developed the idea of ‘history as suffering’ and tried to interpret all events of Korean history in its light. When characterising his nation and people in his book Queen of suffering: A Spiritual History of Korea, Ham writes: ‘This land, this people, events big and small, its politics and religion, its arts and thought all that is Korean bespeaks suffering. It is a fact, however shameful and painful’.5 He always thought of education, faith and rural society as being inextricably related. He was convinced that the salvation of Korea lay in the revival of rural society through faith-centred education. In retelling the history of Korea from this perspective, Ham identifies Korea’s spiritual fate to be suffering, and its calling to be to show the world how to bear that suffering, “without grumbling, without evading, and with determination and seriousness”. This is what will help lead the world to salvation.6 ImprisonmentJapan’s policy in the period 1936-37 became more and crueller, and they vowed to remove all traces of national consciousness from the Korean people. As the school administration intended to compromise with the Japanese policy, he was not allowed to teach, so he left Osan School in the spring of 1938. However, he remained in Osan city as a farmer and taught students through their Sunday meeting for two years. He adopted the traditional Korean dress. In 1940 on hearing a Danish model folk school operated in the outskirts of the P’yongyang, he departed for P’yongyang. However, when he arrived there, the founder of the school was arrested on suspicion of having participated in the independence movement. Ham was also arrested and taken to prison on the same allegation. After one year imprisonment, he was released from prison in 1941, but in 1942 he was once again arrested and imprisoned on charges of anti-Japanese activity through his writings in magazine Bible Korea.7 He was freed from prison a year later. During the Second World War, when, as Ham wrote, “Anyone suspected of having the least bit of nationalistic thought, or liberal thought was arrested on any number of flimsy pretexts and placed in prison to rot ”, he was imprisoned for a year in 1940 and again in 1942. Korea gained its independence from Japan in 1945, but within a month of liberation, the country was occupied by the Soviet Union in the North and the US in the South. Now, as a Christian activist who refused to cooperate with the Soviet military government, Ham once again found himself in prison.8 In prison, he studied the Buddhist Scriptures and read more of Lao-tzu and Chaung-tzu. When he began to read Chaung-tzu, he felt his shell cracking off, bit by bit. He thought genuinely about historical Jesus, eternal life, heaven, salvation, and so on. He declared: The idea of being a heretic or an authentic is an old idea. Where is the road in the air? Go endlessly; endlessly climb up the road. As long as you are a relative being, you are going to go your way, which is just one of the infinite ways. I am only going to go my way. I am not qualified to define it. There is no heresy. Only those who claim to be heresy are heresy.9 He reached the conviction that all religions are one. Because of his view on Korean history, he was imprisoned and suffered much at the hands of the Japanese colonial regime. Ham viewed prison as the University of Life. Sitting in the middle of this cell called Korea or home, and watching the flow of history, his thoughts centred on the following: This flow of history does not stop merely with the changes of national boundaries. It is the beginning of a world revolution in which the structures of human society are changing. The world must become one nation. The view of the state must be revised. The age of the Great Powers has passed. The view of the world is changing, and religion also will change. Will, not it takes on a form quite different from that of the present? The fundamental truth of religion cannot change, but every age demands a new expression of that which is eternal. Every age possesses its keyword. What is the world of the age to come? Who will accept it? Are we not crying for a new Renaissance which can usher in a new period of religious reformation? If so, then there must be a new interpretation of the past. There must be renewed research into the classics. Moreover, since the Western classics have been “used up”, we are forced to examine more closely our Eastern classics. A renewed appreciation of the East will furnish the key to the revitalisation of the stagnated Western culture.10 Although Korea regained its independence in 1945, sadly Ham encountered another oppressive regime of the Soviets. Since he was a Christian activist and took a non-cooperative stance against the communisation policy in the North, he was imprisoned by the Soviet military government. So although Korea was “liberated,” still Ham was imprisoned and beaten, this time by the communists as a Korean patriot.11 The Soviet military government in the North tried to force Ham to be a spy for them, and he escaped to the South in March 1947. However, as he also criticised the corrupt and dictatorial regimes of Syngman Rhee, Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan successively, Ham was again repeatedly persecuted, tortured and imprisoned by the South Korean regimes. He called prison his ‘university’ because he learned so much there.12 In 1947, he fled to South Korea, where over the next forty years he persistently criticised a series of corrupt and dictatorial regimes there. He was impressed by their pacifism, egalitarianism and their active participation in questions of social justice. At the time, however, Ham was still involved with the Non-Church Movement.13 Queen of Suffering: a spiritual history of KoreaHam’s books, starting with the controversial Korean History in 1948, and the later Queen of Suffering: A Spiritual History of Korea are still recognised as among the most notable books in Korea. Ham Sok-Han repeatedly suffered imprisonment and carried out hunger strikes, first under the Japanese occupation of Korea in the 1920s, then under the communists in North Korea and finally under a series of corrupt dictatorships in South Korea. The book Queen of Suffering: a spiritual history of Korea led to his being imprisoned by the Japanese for ‘harbouring dangerous ideas’. It called for Koreans to find a spiritual identity but rejected the path of violence. It closed with the line: “Put your sword down and think hard.”14 He was also a poet and wrote about 120 poems such as “Song of the West Wind” written in 1983. Nonviolence and pacifismAlthough Ham lived under oppressive regimes throughout his entire life, he always stressed the importance of nonviolence and pacifism. At the same time, he eagerly promoted democracy and the freedom of the press, while he heavily criticised the obedient, passive and fatalistic attitude of the people. Perhaps his fundamental thinking can be summarised as “malice toward none” with a strong sense of justice.15 Like Gandhi, to whom he was often compared, Ham believed that sometimes the roads to freedom and love are so blocked by the evil that force may ultimately be necessary to clear them. However, he always considered it last rather than a first resort. “We should keep to the principle of nonviolence”, he said, “but not leave the people who are struggling. We should try to keep with them and to educate them. In the struggle, there are several degrees or states – the best one you should choose the second best or third best one. If you feel that is impossible to follow the best one you should choose the second best or the third one. To keep silent and remain unmoved is much worse than to choose the second or even third state. Still, we must always urge the people to use the best method”.16 Ssial-nongjangHam encouraged peace and democracy and promoted non-violence movement known as “seed idea” (ssi-al sasang), consistently present in his famous books “Korean History Seen through a Will” published in 1948, “Human Revolution” in 1961, “History and People” in 1964, "Queen of Suffering: a spiritual history of Korea" edited in 1985.17 Ham had been an admirer of Gandhi for a long time, having read his Young India while still at Osan school. However, after his death in 1948, I became a more ardent follower, reading more of his books and even forming a small study group. Eventually, some friends suggested establishing a community similar to Gandhi's ashram, and as the land was made readily available in 1957, he opened a farm in the small town of Ch’onan, about thirty miles south of Seoul, on land contributed by a benefactor, where they could live together with selected young persons. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s Tolstoy farm in South Africa, he made Ssial-Songjiang, a collective farm where young farmers studied and worked with him.18 The farm was named Sial which in Korean can mean not only ‘seed’ but also ‘people’ or ‘nation’. Ham Sok Hon has been called the Gandhi of Korea because he articulated a spiritual vision for Korea, not unlike Gandhi, articulated a spiritual vision for independent India. Whereas Gandhi’s vision originated in his understanding of Hindu thought, however, Ham Sok Hon had originated in his understanding of Christianity (and later Buddhism, Confucianism and shamanism).19 When, in the beginning, his friends urged him to serve as the leader of the community, he refused not out of humbleness but because he did not feel that he had the necessary qualifications to direct such a community. However, under pressure, he finally accepted the position, and this was the beginning of his wrongdoing.20 From this time, his situation changed drastically. His friends all avoided him. In this period of agony, when he longed for a friend, the Quakers appeared before him. QuakerHam was formally a Quaker, a non-sectarian Christian denomination. Ham regarded the least form of religious institutionalisation as the best religion. He was especially impressed by the Quakers’ pacifism, egalitarianism, community spirit (group mysticism), and active participation in here-and-now social affairs rather than longing for a “heaven or Kingdom of God” in the afterlife.21 Having learned of Quakers at Osan School, Ham was fascinated by George Fox. During World War II, he was impressed with a large number of Quakers who were conscientious objectors, for he rejected violence absolutely: “Real victory can only be gained by love”. His first direct contact with the Friends was in the 1950s when he met Quakers doing relief work after the Korean War. He began attending the meeting for worship in Seoul and eventually became a member. As Quakers tried to merge and keep a balance between science and religion, rationalism and mysticism, Ham also had such a tendency. Later he spent time at Pendle Hill and Woodbrooke and attended several Friends’ conferences.22 He wrote some 20 books, of which Queen of Suffering: A Spiritual History of Korea and Kicked by God have been translated into English. American Quakers nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 and 1985, making him the first Korean to be nominated. Ham himself felt that he was unworthy. Nonetheless, his life as a Christian, particularly as a Quaker, was an attempt to find the truth within his specific historical era, an era of political oppression and religious narrow-mindedness.23 At the same time, Western Quakers firmly and steadily backed Ham’s civil rights movement when Korea was ruled by authoritarian regimes. American Quakers nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 and 1985, making him the first Korean to be nominated. Ham himself felt that he was unworthy. Nonetheless, his life as a Christian, particularly as a Quaker, was an attempt to find the truth within his specific historical era, an era of political oppression and religious narrow-mindedness. His name for himself was ‘Foolish Bird’, after the Japanese name for the Albatross, aho-dori or baka-dori (stupid bird) which cannot catch its fish but lives off scraps. Perhaps his lifestyle was the same as the albatross. Others knew him affectionately as ‘Teacher Ham’. Though his heart beheld and stayed with the blue sky or idealism, he was not able to earn even a piece of bread to eat. His daily bread was given by his friends and neighbours. In sociological terms, Ham was a marginalised individual. However, Lao-tzu, Jesus, Socrates and John the Baptist were also marginalised individuals in their time. Perhaps it was this social marginality that helped to form his unique character.24 Ham continued to speak out against dictatorship and injustice in South Korea. He carried out a hunger strike in 1965, was imprisoned in 1976 and 1979, and was placed under house arrest in 1980. South Korea finally achieved full democracy in 1987. In 1988, due to massive demonstrations and protests, General Doo-Hwan Chun reluctantly resigned from the presidency. On the eve of the International Seoul Olympiad, Sok Hon Ham rose from his hospital bed to convene the Seoul Assembly for a peaceful Olympiad. As the Head of the Seoul Peace Olympiad he represented the Korean people. This organization drew up a declaration calling for world peace which was signed by more than six hundred prominent citizens, including Nobel Peace Prize winners and world leaders. Four months later, on February 4, 1989, he finished his journey of suffering at the Seoul University hospital.25 National Cultural FigureHam’s activities were the voice of deprived Korean people when the masses had lost their rights, dignity, and a voice for themselves. When, in the minds of countless Koreans, democracy was but a dream, not a reality, Ham was the symbol of the free man and the personification of democratic ideals. It seemed to Ham that democracy was a kind of religion and that he wanted it to be in a real sense the religion of his fellow Koreans. In 2000 Korea selected Ham posthumously as a National Cultural Figure. Ham can be considered a moral hero. He was not a dexterous politician but was a moral man and eternal visionary.26 After his death, he received the “Accolade for Founding a Nation”, as a sign of recognition from the nation in 2002. He is a representative of the many people who has suffered, been tortured, imprisoned or even killed in the fight for democracy in Korea. He is a symbol of Korea's conscience throughout the era of Japanese colonialism in the Korean peninsula, communist totalitarianism in North Korea, and military dictatorship in South Korea. He was designated as a national cultural figure by the South Korean government. End Notes

* Principal (Retd.), Kamarajar Govts. Arts College, Surandai, Tirunelveli Dist. Tamil Nadu | Email: eraponnu@gmail.com |