Champaran Satyagraha: A revolution of consciousness |

- By Rajdeep Pathak*The legacy calls us to act with the same courage, humility, and resolve that defined Gandhi’s first Satyagraha

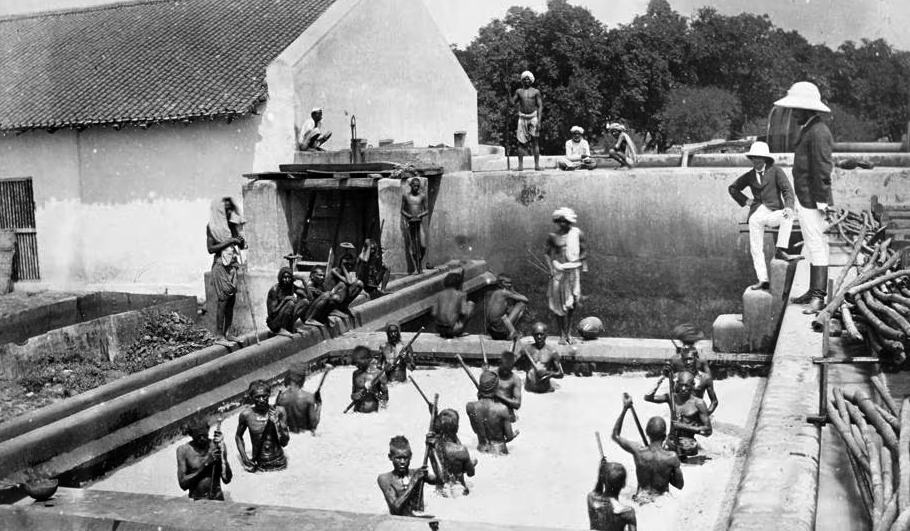

On April 17, 1917, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi set foot in Champaran, Bihar, responding to the desperate appeals of local indigo farmers – specifically Rajkumar Shukla – subjected to harsh colonial exploitation. This moment would mark Gandhi’s first major civil disobedience movement in India — after his successful sojourn in South Africa, where he launched the Satyagraha movement on September 11, 1906 – and a watershed in the nation’s freedom struggle. It was not just a political mobilisation, but a moral and social awakening that would shape India’s destiny. The Champaran Satyagraha that unfolded on April 17, 1917, elevated Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to the political arena of British-dominated India, where Gandhi initiated a forceful non-violent campaign of non-cooperation against injustices. During his 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi had somewhat mastered this art. At the heart of the crisis (in Champaran) was the Tinkathia system, which compelled tenants to grow indigo on three out of every 20 kathas of their land, regardless of soil quality or market viability. This coercive practice was enforced by British planters through manipulative lease agreements with local zamindars, plunging the farmers into cycles of debt and deprivation. Even when synthetic dyes replaced natural indigo in European markets, the system continued solely to serve the exploiters’ profits. This rigid structure contributed to food scarcity and soil degradation, and deepened agrarian distress. Finally, succumbing to the unyielding persuasion of Pt. Rajkumar Shukla, when Mahatma Gandhi arrived in the Motihari District of Champaran, he received a grand welcome to his surprise from the locals, who felt that a messiah had landed on the soil of Bihar for its redemption from the British atrocities. Gandhi did not commence his campaign with fiery speeches or grand proclamations. Instead, he chose to listen. Sitting under trees with farmers, he patiently recorded over 8,000 testimonies, carefully documenting their hardships. He understood that illiteracy and ignorance were instruments of oppression. In response, he initiated community education programmes in villages such as Barharwa Lakhansen, Bhitiharwa, and Madhuban. He also urged his wife, Kasturba Gandhi, to join this mission by imparting lessons on basic health, education and hygiene, which she willingly did and became quite popular amongst the local female folks. The basic motive behind this was to impart literacy, hygiene and vocational skills, combining practical knowledge with the Gandhian ideal of self-reliance. A team of volunteers and educators emerged alongside him – Babu Rajendra Prasad, Acharya JB Kripalani, Acharya Narendra Dev, Gaya Babu, Babu Brajkishore, and many others. They worked tirelessly to spread awareness, organise community efforts, and offer support to the oppressed, besides documenting the agrarian crisis the indigo farmers faced. Kasturba Gandhi’s pivotal role and her efforts sowed seeds of grassroots empowerment. Gandhi, in turn, gave voice to those long silenced by fear and poverty. Women’s participation, often underemphasised in historical narratives, was crucial to the movement’s success. Kasturba Gandhi led by example, and local women began to share their lived realities, forming a collective narrative of resilience. Their involvement defied social conventions and revealed the deep inclusivity of Gandhi’s mission. The psychological transformation that took place in Champaran was perhaps the most profound. Gandhi’s non-violent defiance of the British order to leave the district sent ripples across the colonial administration. For the farmers, it was the first time someone of stature had refused to bow before imperial authority on their behalf. This shift – from fear to self-belief – was a monumental turning point in the Indian psyche. Environmental degradation caused by indigo cultivation was also central to the crisis. Forced monoculture had depleted the soil and undermined food security. Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy for diversified farming practices and local autonomy indirectly promoted sustainable agriculture – long before the term became fashionable in development discourse. Rather than advocating vengeance, Mahatma Gandhi sought justice through reconciliation. When the British government formed a commission to investigate the peasants’ grievances, Gandhi was invited to join it. His presence ensured fair representation of the farmers’ voices. Eventually, the committee recommended the abolition of the Tinkathia system and a partial refund of the illegal dues extracted. The ‘Champaran Agrarian Act of 1917’, which followed, became a landmark in colonial legal reform. Intellectuals and leaders across India took notice. Rabindranath Tagore hailed Mahatma Gandhi’s moral courage. Jawaharlal Nehru saw in Champaran the power of mobilised masses. For Dr Rajendra Prasad, who went on to become Independent India’s first President, it was a training ground in ‘servant leadership’. Historian Bipan Chandra later observed that Champaran redefined the nature of Indian nationalism – from elite dialogue to people’s participation. Champaran was thus more than a protest – it was a revolution of consciousness. It demonstrated that civil resistance rooted in truth and compassion could dismantle entrenched systems of oppression. It linked agrarian justice, education, women’s rights, environmental sustainability, and political autonomy in a way that no earlier movement had done. Today, Champaran remains a luminous chapter in India’s history, a living testimony to the strength of collective action guided by moral clarity. As we commemorate the 108th anniversary of this powerful non-violent satyagraha of compassion and empathy led by Mahatma Gandhi, it is imperative to point out how Mahatma Gandhi had, for the first time, fought on issues of ‘identity’ and ‘human rights’ in the Indian soil after his 21 years in South Africa As we navigate modern challenges — agrarian distress, ecological imbalance, and social inequality — Champaran’s legacy calls us to act with the same courage, humility, and resolve that defined Gandhi’s first Satyagraha – the power of non-violence. Courtesy: This article was originally published in Meghalaya Monitor, dated 19.04.2025. * The author is Programme Executive at Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti, New Delhi, India. |