Dadabhai Naoroji: When the Subaltern Spoke |

- By Anil Nauriya* In September 2025 it will be 200 years since the birth of Dadabhai Naoroji (1825–1917). He was not only a founder and thrice President of the Indian National Congress (INC) (at Calcutta in 1886, Lahore in 1893 and again at Calcutta in 1906), but also the first to refer in a Presidential address (of 1906) to Swaraj (self-government) as the aim and objective of the INC (Deva, 1949: 22). Naoroji had been the first Indian to be elected to the British Parliament in 1892 and had used his mathematical skills and aptitude to scrutinise the economic relations between India and Britain and to examine the causes of India’s poverty. The economic understanding of this articulate subaltern who gave voice also to the subalterns of the Empire, influenced India’s freedom movement. A biographer of Joseph Baptista, leading light of India’s Home Rule movement, acknowledged, ‘The analysis made by Dadabhai Naoroji as also his criticism of the systematic colonial exploitation of India were widely followed by progressive circles’.1 Naoroji’s work inspired India’s freedom fighters including M. K. Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Lajpat Rai and others (Rai, 1967: xxxiii, 195). Naoroji’s 'drain theory' emerged from his examination of the relation between India as a colony and Britain as the ruling power. He was prompted by the rural crisis in Orissa (now Odisha) in the mid-1860s to scrutinise the British administration’s revenue policies, and to attribute to these the continuing and aggravated prevalence of poverty. He was the progenitor of poverty studies in India. The socialist movement in post-independence India too owes Naoroji an obvious debt as the searchlight which it focussed in the 1960s on Indian poverty was rooted partly in the Naoroji tradition that also inspired the objectives of the—now abolished—Planning Commission. Naoroji’s study of India’s economic exploitation by the alien administration of a colonial power has its relevance also in the context of India’s place in the contemporary global financial system. India is still seen largely as a market to be exploited and the tendency of economic governance in recent years has also been to dilute whatever autonomous capacities were built up in the form of a strong public sector.

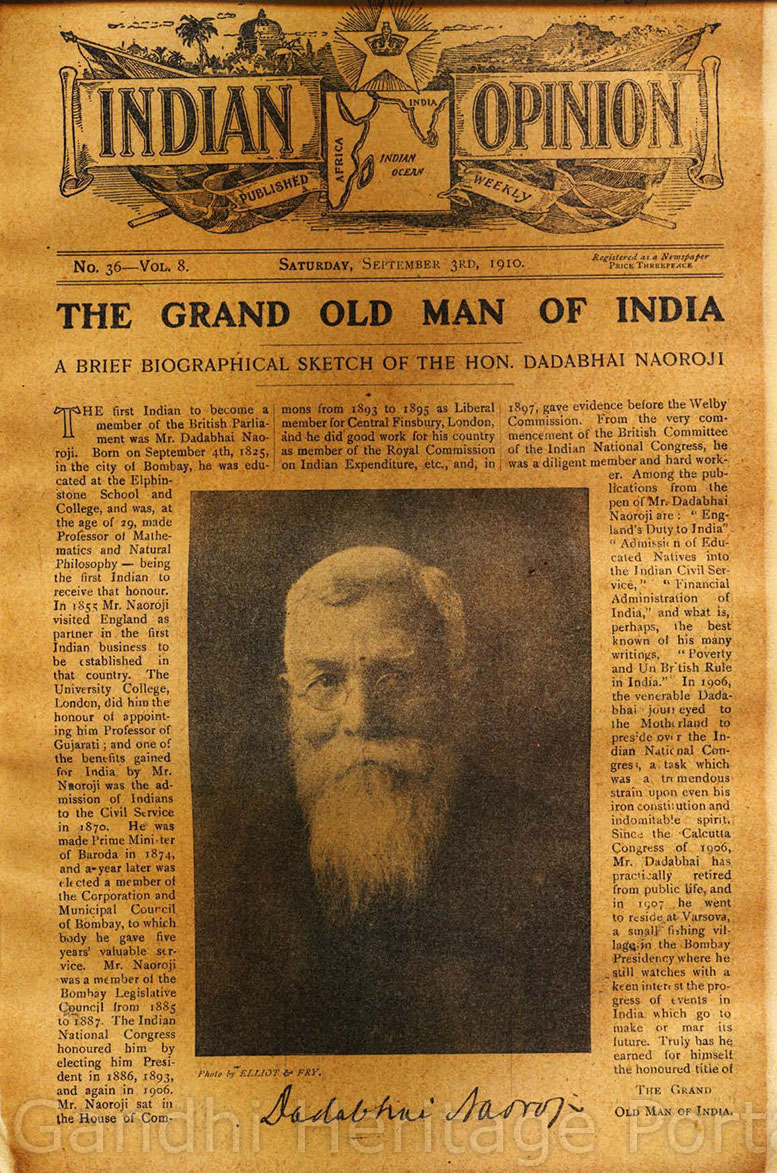

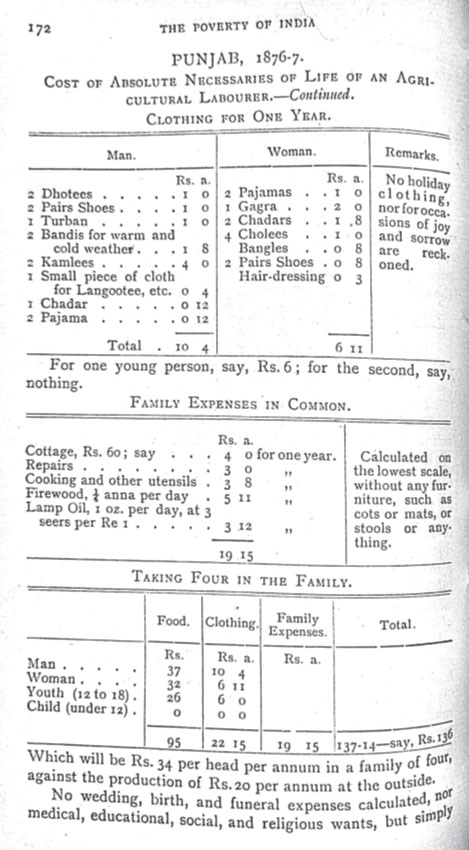

Front page of M.K. Gandhi’s journal in South Africa, Indian Opinion, dated 3 September 1910, the eve of Dadabhai Naoroji’s birthday The personal achievements and public contributions of the Grand Old Man of India extend from his becoming the first Indian Professor (Mathematics and Natural Philosophy) at the Elphinstone institution in Bombay, to helping pioneer female education, to his efforts for social and political reform and to his relentless academic pursuits, even in England, along with the commercial engagements that had taken him there for the first time in 1855. This was in addition to his institution-building efforts both in India and in England, his public, political and electoral campaigns, his academic exercises and his journalistic ventures. There was an underlying unity between all of Naoroji’s activities—the cause of oppressed peoples. It is useful to remember that Naoroji had guided M. K. Gandhi in the latter’s South African years. On 5 July 1894, the not-yet-25-year-old Gandhi had written to Naoroji from Durban: I am yet inexperienced and young and, therefore, quite liable to make mistakes. The responsibility undertaken is quite out of proportion to my ability....You will, therefore, oblige me very greatly if you will kindly direct and guide me and make necessary suggestions which shall be received as from a father to his child.2 Fifteen years later, when some commentators were apt to make light of Naoroji’s contribution, M. K. Gandhi, still in South Africa, reprimanded them thus in his work Hind Swaraj (1909), translated as Indian Home Rule (1910): I must tell you, with all gentleness, that it must be a matter of shame for us that you should speak about that great man in terms of disrespect. Just look at his work. He has dedicated his life to the service of India. We have learned what we know from him. It was the respected Dadabhai who taught us that the English had sucked our life-blood....What does it matter that, today, his trust is still in the English nation? Is Dadabhai less to be honoured because, in the exuberance of youth, we are prepared to go a step further? Are we, on that account, wiser than he? It is a mark of wisdom not to kick away the very step from which we have risen higher. The removal of a step from a staircase brings down the whole of it....He would always command my respect. Such is the case with the Grand Old Man of India. We must admit that he is the author of nationalism.3 In 1849 the 24-year-old Naoroji was associated, along with a dozen Elphinstonians, in the establishing of six schools for girls. The network behind this would evolve into and coalesce in the Bombay Association; it was in a speech at the inauguration of this Association in August 1852 that Naoroji had attributed the impoverishment of peasants to ‘bad administration’ or faulty governance (Patel, 2020: 61). It is the connection between these features that Naoroji would relentlessly pursue during the rest of his career. A little earlier, in 1851, Naoroji had co-founded the Rast Goftar (The Truth-Teller), a Gujarati journal devoted to social reform. Although it was focussed especially on the Parsi community, Naoroji ‘made a declaration pledging his paper to the service of all Indians irrespective of caste or creed’ (Natarajan, 1955: 60). Naoroji’s economic and political ideas evolved rapidly as he began documenting the relation between Indian poverty and British rule. Nearly a million people, being a third of Orissa’s population, perished in the famine of 1866 (Dutt, 1900: 8–9). This crisis quickened Naoroji’s critique of the economic drain from India (Naoroji, 1901: 33–45). He analysed price data for several crops from various places across India and wage data including wages of women labourers and boys in certain regions (ibid.: 62–85). He linked the fragility of rural existence to the burden of excessive taxation and that taxation itself as only one of the many modes of colonial extraction from India which ‘are fast bleeding the masses to death’ (ibid.: ix–x). The distinction that Naoroji made between British colonial extraction and preceding ruling dispensations seeped deep into Indian political understanding (Sharma, 1982: 340–69). Examining data minutely, he sought correctives. Making a comparison of statistics on sugar production per acre in Delhi and Punjab, he cast doubt on the credibility of data which showed the sugar yield in Delhi to be higher than in the more fertile Ludhiana area (Patel, 2020: 58). It is to the Select Committee on Indian Finance that Naoroji made the submission in 1873 that would later become known as Poverty of India (1878). Naoroji also had a stint in the princely state of Baroda in 1874 when he was Dewan or Prime Minister. Naoroji was a very independent-minded member of the Bombay Municipality (1873–1876).4 By the early 1880s even British officialdom had substantially conceded the correctness of Naoroji’s estimate of per capita annual income in India; he had computed it as Rs 20 while the Finance Member, Sir E. Baring (later Lord Cromer) in his budget speech of 1882 put it at Rs 27 (Naoroji, 1901: 243; Joshi, 1890, 757–58). Though Naoroji’s methods of estimation are said to have been ‘rough’, it is generally conceded that his interprovincial rankings were valid even in the 1930s (Goldsmith, 1983: 7 and 7n). On pauperisation, Naoroji had already shown in an earlier study in 1880 (later reprinted in Poverty and Un-British Rule in India) that the basic necessaries for even an agricultural labourer in Punjab, for which statistics could be put together (see Figure 2), would cost far more than the per head per annum income conceded by the government (1901: 172–73). In 1885–86 Naoroji was appointed a Member of the Legislative Council of Bombay. Founding of the INCAt a meeting held on the retirement of Lord Ripon as Viceroy in 1884, the year before the founding of the INC, Naoroji spoke of self-government and self-administration (Masani, 1939: 219–20). On the political front efforts were afoot in Bengal, Bombay, Madras and elsewhere for the establishment of a national organisation. Bengal had been making its advances towards political organisation with Surendranath Banerjea and others taking the initiative to establish an Indian Association in 1876 (Sitaramayya, 1935: 14). The Madras picture is presented by Annie Besant in her work, How India Wrought for Freedom (1915). This work, dedicated to the ‘Motherland’ and to its ‘noble son’ Dadabhai Naoroji, refers to his presence among a group of 17 persons who gathered at Dewan Bahadur Raghunath Rao’s Madras residence in December 1884. It is at this meeting, according to Besant, that a plan to call a national convention was set in motion (1915: 1–4).5 Various writers differ in the weight to be attached to particular meetings held prior to the actual foundation of the Congress in 1885 (see, Mehrotra, 1995: 1–16).   Table from Naoroji. 1901. Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, pp. 172–173 Naoroji’s biographer, R. P. Masani wrote about the founding of the INC: Dadabhai was one of the moving spirits. Of the founders the most conspicuous was A. O. Hume, a retired member of the Indian Civil Service but an ardent and active supporter of India’s struggle for freedom. At the first Congress, which held its sittings in Bombay in December 1885, Dadabhai took an active part. In almost all the resolutions adopted at that session one could easily discern his hand, particularly in the very first proposition, which approved of the promised committee of inquiry into the working of the Indian administration. One of the resolutions, praying for simultaneous examinations for the Indian Civil Service, was moved by him (1939: 226). Referring to those early days, Jawaharlal Nehru would write of the founders, ‘…one name towers above all others—that of Dadabhai Naoroji, who became the Grand Old Man of India, and who first used the word Swaraj for India’s goal’.6 Chimanlal Setalvad, then a law student present as a visitor on the occasion of the founding of the INC, would recall: ‘It was truly a national gathering comprising leading people from all parts of India, from the extreme north to the extreme south, and including all communities’ (1946: 274–75). A vivid account of the personalities, including Naoroji, present at the founding of the Congress is reproduced by S. R. Mehrotra in his work, The Emergence of the Indian National Congress. The account is originally by a ‘Special Correspondent’ who wrote in the Reis and Rayyet journal issue of 30 January 1886 under the penname Chiel (Mehrotra, 1971: 595–98). After the INC was founded in December 1885, Naoroji proceeded with his plan to go to England in 1886 to influence opinion there. He made his first electoral attempt to enter the British Parliament in mid-1886. This was very much in the framework of the overall policy of the INC at the time, as many of its stalwarts saw little hope of making a dent on colonial administration and policy unless an effort was made in England. Naoroji sought out socialists, Irish Home Rule activists, workers and suffragists. Naoroji returned briefly to preside over the second session of the Indian National Congress held at Calcutta in December 1886. A ‘very old man’, Jaikishan Mukerji, described as ‘blind and trembling with age’, proposed Naoroji’s name as President (Besant, 1915: 16). In the course of his presidential address Naoroji set at rest, as was then his wont, the idea that the Congress was a ‘nursery for sedition and rebellion’ (Masani, 1939: 53). While excluding social issues, he defined the Congress as a political body devoted to ‘questions in which the entire nation has a direct participation’, thus emphasizing both Indian nationhood and representation (ibid.: 253–54). A related organisation, the Indian National Social Conference, was established in the following year at the initiative of M. G. Ranade and Raghunath Rao (Prasad, 1965: 19). Naoroji himself accepted in his writings the ‘humane influence’ of Britain in such reforms as the abolition of sati and of infanticide (Naoroji, 1901: vi). Contrary to narratives that set the two organisations on mutually exclusive paths, both Naoroji and Ranade understood the symbiotic dynamic between them; it is Ranade who in his last public act unveiled a portrait of Dadabhai Naoroji at Bombay in 1900 (Kellock, 1926: 192–93). Chimanlal Setalvad refers to a deputation from the Congress, headed by Naoroji, to Lord Dufferin, the then Viceroy, to press for separation of executive and judicial functions in India, a demand whose desirability had been earlier stressed by Raja Ram Mohan Roy (Setalvad, 1946: 164–65). Naoroji also utilised his few weeks in India during the 1886–87 winter to give evidence before the Public Service Commission in Bombay.7 On civil service examinations, he raised his long-standing grievance. According to him, Any proposal to fix a portion of the service to be allotted to natives would, violate the fundamental principle of the Act of 1833 and of the Proclamation of 1858. Should, however, Government be not prepared to do full justice....Government may, for the present, provide that until further experience was obtained, a quarter or half of the successful candidates should be English.8 Naoroji objected to the requirement of temporary residence in England precedent to first competition as he considered that exclusionary of Indians at large (Masani, 1939: 255). His concerns were not confined to the civil services but extended to other fields as well; for example, he analysed the employment opportunities of those Indians who had graduated from certain engineering colleges, such as in Roorkee, to ask why the Indian intake was kept low (Naoroji, 1901: 111–14). In London, Naoroji had founded the East India Association in 1866 with membership open to all interested in India’s welfare (Masani, 1939: 100–01).He was elected to the British Parliament from Central Finsbury in 1892. Among those who worked for him in this election, apart from a number of enlightened friends of India, was the student Sachchidananda Sinha who, in 1946, would be the pro tem President of the Constituent Assembly of India (Sinha, 1976: 195). Naoroji’s membership during 1892 to 1895 had a significant impact both on England and India. An important high point of this tenure was the resolution for simultaneous civil service examinations (in India and England) that was dramatically passed in the House of Commons on 2 June 1893, taking the Gladstone government by surprise. It was Naoroji’s resolution introduced by Herbert Paul and seconded by Naoroji after considerable preparation by both. The point of simultaneous examinations was to enhance Indian recruitment in the civil service. It was to the alien nature of this service to which Naoroji had been tracing more than a ‘century of misrule in India’ (Masani, 1939: 334). The resolution placed a moral obligation upon the government and brought the question of racial nondiscrimination in governance into public focus. Naoroji’s tour of India to preside over the Indian National Congress session at Lahore in 1893–94 evoked an impressive response. The tour had taken him to Poona where he was met by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Dinshaw Wacha and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, among others (Parvate, 1959: 49–50). Later he travelled by train from Bombay, touching Surat and Baroda before reaching Ahmedabad and then through an illuminated Beawar and Ajmer in Rajasthan, and Delhi, where Naoroji was ‘...at the head of a procession of four hundred carriages...that moved down... Chandni Chowk’ (Patel, 2020: 206–13; see also Masani, 1939: 341–49); there were welcoming gatherings at Ambala, Ludhiana, Phagwara and Jalandhar, and a halt at Amritsar where Naoroji was taken to the Golden Temple, before his train finally reached Lahore which put its pluralism on display to accord him a classic welcome with a memorable four-hour-long procession that moved through various parts of the city including Anarkali Bazaar (ibid.). At Delhi there had been another unusual scene: ‘As the train bringing Mr Naoroji entered the suburbs of Delhi the mill hands of “Delhi Weaving and Spinning Mills” and of “Krishna Flour Mills” cheered lustily and gave him a hearty welcome’ (no author, 1898: 172). A warm welcome awaited Naoroji in Lahore, including by the Muslims of that city with a public address read by Moulvi Muharram Ali Chishti (ibid.: 163). At the Lahore session, the Chairman of the Reception Committee Sardar Dayal Singh Majithia welcomed the delegates. Thereafter, Ananda Charlu formally proposed and Muharram Ali seconded that Naoroji preside over the session (Besant, 1915: 162–63). In his Presidential address at Lahore, Naoroji called for direct representation in Parliament from India. He referred to calculations of Indian income and showed how even official figures substantively conceded his point about the low income in India of Rs 20 per head per annum. Naoroji referred to the margin of difference with the official figures thus: ‘However, Rs 20 or “not more than Rs 27”—how wretched is the condition of a country of such income, after a hundred years of the most costly administration, and can such a thing last?’9 Although he reiterated his faith in British fair play, he concluded, ‘Our fate and our future are in our own hands’.10 His speech led to a widespread discussion in the country. After presiding over the Lahore Congress, Naoroji moved through Kanpur, Agra, Aligarh and Allahabad before returning to Bombay. The Times of India reported on 5 January 1894: ‘At Aligarh he was warmly welcomed by Sir Syed Ahmed’ (no author, 1898: 143). Among the great achievements of Naoroji’s parliamentary and other work in England was the appointment in 1895 of the ‘Royal Commission on the Administration of the Expenditure of India’, popularly known as the Welby Commission, after its Chairman Reginald Earle Welby. The issues entrusted to this Commission went to the root of the concerns Naoroji had been raising about the economic and administrative relationship between India and Britain. Naoroji was not only a member of the Commission and the first Indian to become a member of such a commission, but also gave extensive evidence before it as a witness. Naoroji had wanted M. G. Ranade to join him in giving evidence but the latter was prevented by the Government of India for both political and technical reasons. Ranade sent Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Naoroji used the opportunity of the Commission to make sharp attacks on the government. It appears that by this time Naoroji’s activities had begun to cause considerable irritation to influential sections of the British establishment.11 The 19th century drew to a close with Dadabhai Naoroji’s submissions to the Indian Currency Committee of 1898 (also known as the Fowler Committee). This submission contained, towards the end, this comment: The only reason the Indian Government does not go into bankruptcy—bankrupt though it always is—is that it can, by its despotism, squeeze out more and more from the helpless taxpayer, without mercy or without any let or hindrance. And if at any time it feels fear at the possible exasperation of the people at the enormity, it quietly borrows and adds to the permanent burden of the people without the slightest compunction or concern. Of course, the Government of India can never become bankrupt till retribution comes and the whole ends in disaster.12 Naoroji’s relentless examination over the years of the condition of India, the causes of the poverty of its people, and the wants and means of India were brought together in the classic work Poverty and Un-British Rule in India (1901). It contains minute comparisons of wage levels, including for women and children. Its impact on the course of India’s subsequent history is manifest and incommensurable.13 Apart from the multifarious conversations on famines, poverty, national income, national accounting, Imperial charges imposed on India and the drain of its wealth, there is also Dadabhai Naoroji’s trenchant critique of the Salt tax.14 After referring to the opium trade, Naoroji wrote: In association with this trade is the stigma of the Salt-tax upon the British name. What a humiliating confession to say that, after the length of the British rule, the people are in such a wretched plight that they have nothing that Government can tax, and that Government must, therefore, tax an absolute necessary of life to an inordinate extent! (1901: 215). M.K. Gandhi, who paid close attention to all that the Grand Old Man did or wrote, would—some three decades later—choose this precise issue on which to organise a nation-wide defiance movement. Gradually but surely, Dadabhai Naoroji had come to the conclusion that robust self-government was the only remedy for the Indian predicament. He had seen that the unequal economy was inherent in a non-self-governing arrangement. Referring to workers in foreign-owned mines and plantations, Naoroji noted in a speech at Portsmouth in 1903 that they were ‘mere slaves, to slave upon their own land, and their own resources in order to give away the products to the British capitalists’.15 Amsterdam International Socialist Conference, 1904Naoroji attended and addressed the Amsterdam Socialist Congress in 1904. In a warm welcome, the President of the Conference, Henri van Kol, spoke of Naoroji’s long struggle for the ‘freedom and happiness’ of his people (Braunthal, 1966: 312). The Grand Old Man of India received a standing ovation at the conference which was also attended by Rosa Luxemburg, Jean Jaures, Karl Kautsky and Henry Hyndman. Naoroji spoke about the drain of India’s wealth and its connection with the country’s poverty. He called for self-government for India and that it be treated on par with the British self-governing colonies. The importance of this first Indian representation associated with India’s leading political movement at an International Conference of Socialists is self-evident. At this conference Naoroji defined ‘working men’ as constituting ‘the immense majority of the people of India’. The Anglo-Indian press in India was critical of Naoroji’s participation. Later, when Indian socialist and communist groups became active in the 20th century they did not hearken to this and similar insightful interventions by Naoroji on the rights of labour. But leading Indian nationalists and socialists in India continued to refer to Naoroji as an inspiration even towards the end of the 20th century. The Congress Socialist Party was born within the Indian National Congress 30 years later in 1934; yet the roots of socialist thought and the socialist movement in India go back at least to 1904 when Naoroji attended the Amsterdam International Socialist Congress. Naoroji was widely referred to both by socialists and other freedom fighters in India. Among those who influenced Madan Mohan Malaviya’s views on ‘economic and financial issues’, writes one of his intellectual biographers, were ‘specially Naoroji, Dutt and Ranade’ (Gupta, 1978: 88). Jawaharlal Nehru acknowledged in his work An Autobiography that ‘Dadabhai Naoroji’s Poverty and Un-British Rule in India and books by Romesh Dutt and William Digby and others played a revolutionary role in the development of our nationalist thought’ (1984: 426). Referring to Sakharam Ganesh Deoskar’s work Desher Katha, two scholars observe, Substantially based on the works of Digby, Naoroji and Dutt and written in elegant style, this Bengali work powerfully influenced the minds of thousands of men in the exciting Swadeshi times. It ran through the fourth edition as early as October 1907. About this work Sri Aurobindo wrote, ‘This book had an immense repercussion in Bengal, captured the mind of Young Bengal and assisted more than anything else in the preparation of the Swadeshi movement’ (Mukherjee and Mukherjee, 1958: 8). A socialist freedom fighter born in 1920 in Sialkot (now in Pakistan) recalled having read Naoroji in Urdu: The first Urdu book I completely read was by Dadabhai....It was the village economy, according to him, that was completely ruined. There was an ample record of agrarian distress and almost all the provinces were mentioned by name....Perhaps this was the reason for the rise of rural and national movements in India (Toofan, 1995: 110). At least one Marathi biography of Naoroji is known to have been available by the start of the Non-cooperation movement in 1920 (Phadke, 1920). By 1923 a Hindi language biography of Naoroji was also extant (Sharma, 1923). A Gujarati text of Naoroji’s work on the poverty of India was published by Gujarat Vidyapith under the title Hindustani Garibai (Naoroji, 1938). Romesh Chunder Dutt wrote to Naoroji on 11 July 1903: I have never lost a single chance of urging that the drain from India is the cause of her poverty....If you were right in combining the land revenue question with the drain question in 1873 I am right in doing the same in 1903 (Masani, 1939: 523–24). Naoroji’s ideas on the civil service (including the need for simultaneous examinations in India and England), the drain of resources from India and the origin and causes of India’s continued poverty were interconnected. Many of Naoroji’s African and African diaspora linkages have been traced by a recent biographer, Dinyar Patel. Some of the remarkable contacts that Naoroji made were with Ida B. Wells, Henry Sylvester Williams and W.E.B. Du Bois. It was after being moved by Ida B. Wells’ testimony on racist mob violence in the United States that Naoroji joined ‘a group of progressive MPs, journalists, and clergymen in founding an English Anti-Lynching Committee’; later, Naoroji helped Henry Sylvester Williams in the organisation of the Pan-African Congress of 1900 in London.16 The year 1906 proved to be a fateful and eventful one. W.C. Bonnerjea, the first President of the Indian National Congress, passed away in London in July 1906; Naoroji and Romesh Chunder Dutt spoke at his funeral (Gupta, 1911: 460). In August Badruddin Tyabji, the third President of the Indian National Congress, also passed away in London. In the same month, Ananda Mohan Bose, who had been Congress President in 1898, passed away in Calcutta. Naoroji presided over the meeting held in London to mourn both B. Tyabji and A. M. Bose (ibid.: 460–61). Later in the year Naoroji, ever watchful of Indian causes, accompanied M. K. Gandhi, who was visiting London from South Africa, to meetings with Lord Elgin, the Secretary for the Colonies, and John Morley, the Secretary of State for India. Calcutta Session of the INC, 1906The year 1906 drew to a close with Naoroji being accepted by both moderate and extremist sections of the Indian National Congress to preside over the Calcutta session in 1906. After Dadabhai sent his consent, Bal Gangadhar Tilak withdrew his name from the fray and endorsed Dadabhai (Parvate, 1959: 224). Naoroji’s name was formally proposed by Peary Mohan Mukerjee and seconded by Nawab Syed Muhammad (Besant, 1915: 443). ‘In 1906 at Calcutta, for the first time since Congress had been organized 21 years before, the demand for Swaraj was made in the Presidential Address by Dadabhai Naoroji’, notes Madho Prasad, an editor of M. K. Gandhi’s Collected Works (Prasad, 1965: 30). Gokhale read out the bulk of Naoroji’s address. In this address Naoroji answered the imperial critics of Indian selfgovernment: ‘We can never be fit till we actually undertake the work and the responsibility’ (Patel, 2020: 247). In this speech Naoroji made a further advance in his position by demanding reparation for ‘past sufferings’ (ibid.: 246). Chimanlal Setalvad would recall: ‘Dadabhai Naoroji was elected to preside over the session for the third time. The President, Pherozeshah (Mehta), myself, Jinnah, Dinsha Wacha and Rustom K. R. Cama were the guests of the Maharaja of Darbhanga at his Chowringhee House’ (1946: 279). Among those present at this session in various capacities were Sardar Ajit Singh, C. F. Andrews and, as volunteers, Sunder Lal and Rajendra Prasad.17 The latter’s presence meant that the Constituent Assembly of (undivided) India—to be established 40 years later—would, both through its pro tem President—Sinha, a Naoroji lieutenant referred to earlier—and its elected President have a Naoroji link, if not imprimatur. In his memoir, Sunder Lal recalls the enthusiastic participation of Bengal’s Atiqullah Khan at the 1906 Congress (Chaturvedi and Pande, 1986: 38). Andrews was impressed by the greatness of Naoroji’s vision but regretted the exclusion of social issues from the ambit of the Congress (Chaturvedi and Sykes, 1971: 50–51). Two important resolutions passed at the 1906 session related respectively to the endorsement of the boycott movement inaugurated in Bengal consequent on its partition and support for the Swadeshi movement ‘to promote the growth of indigenous industries’ by ‘giving indigenous articles preference over imported commodities, even at some sacrifice’ (Nevinson, 1975: 183). Parts of Naoroji’s Calcutta address of 1906 were printed by the African-American intellectual and campaigner W. E. B. Du Bois in his journal; Du Bois praised Naoroji’s speech as ‘worthy of men who want to be free’ (Patel, 2020: 251). Naoroji went back to England, only to return to India in 1907—this time for good. His wife Gulbai passed away in 1909.In September 1915 he agreed to become President of the Home Rule League set up by Annie Besant. By 1917 Dadabhai Naoroji had retired from public life. Visana (2022) suggests that Naoroji made a speech in the Indian Legislative Council in February 1917; this is probably an error arising from confusion with Sir Maneckji Byramjee Dadabhoy who was a member of the Council till that year.18 Dadabhai Naoroji passed away in Bombay in the evening of 30 June 1917, at a time when his disciple M. K. Gandhi was in Motihari with the peasants of Champaran. It seems in some ways appropriate that the condolence meeting Gandhi presided over was held there (Dalal, 1971: 14). Granddaughters of Dadabhai NaorojiDuring the discussion in the Constituent Assembly of India on the National Flag in July 1947, Sarojini Naidu referred, among others, to ‘the smallest community in India, the Parsi community, the community of that grand old man Dadabhai Naoroji, whose granddaughters too fought side by side with the others, suffered imprisonment and made sacrifices for the freedom of India’ (Constituent Assembly of India, 1947: 791). Naoroji’s granddaughter Perin was connected in Paris to the revolutionary Indian woman Bhikaiji Cama. During the Noncooperation Movement of the 1920s, Perin, along with Sarojini Naidu, organised the Rashtriya Stree Sabha (Nauriya, 2021: 2–3). Perin Captain became President of the Bombay Congress and was jailed in the Civil Disobedience Movement in 1930. Perin’s sister, Goshibehn too had been associated with the founding of the Rashtriya Stree Sabha and had also presided over meetings held during the Civil Disobedience movements. Khurshed Naoroji, another granddaughter of Naoroji, also left a mark on the Indian struggle, often accompanying M. K. Gandhi and his wife Kasturba on their tours across India, working in the North West Frontier Province in the 1940s and being jailed there as well as in the Bombay Presidency (Bohra, 1988: 246–48). She also worked off and on as M. K. Gandhi’s secretary.19 At some stage, 42 years after Dadabhai Naoroji’s Amsterdam address, she even threw in her lot with the Congress Socialist Party, eliciting from Gandhi an affectionate note with the response, ‘You have done well to join the C. S. P.’.20 At this time the CSP group was still part of the Indian National Congress. Another Naoroji granddaughter, Nargisbehn Captain, was also associated with the national struggle, contributing to various aspects of it including the popularization of khadi and the promotion of the Hindustani language; Perin Captain was especially active in the promotion of Hindustani. The colonial government naturally kept a wary eye on the sisters whom they believed to be in direct or indirect contact with Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s ‘Red Shirt’ organisation. Aspects of Naoroji’s life and work, including the method of painstaking fact-finding and inquiry before initiating any agitation or struggle were internalised in the struggle for independence. But this tradition probably needs further nurturing in post-independence India. After Independence the Naoroji legacy has continued to be celebrated in India, albeit in a general way and in fits and starts. The centenary of his 1892 election to the British House of Commons was observed in association with the India International Centre and Delhi’s Parsi Anjuman on 20 December 1992, inaugurated by the then Vice President of India, K. R. Narayanan. The publication marking the occasion contains a message from the then President of India, Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma. The Presidential message, significantly dated 7 December 1992, recalled that Naoroji was ‘a leading social reformer who dedicated himself to the noble ideals of secularism and human rights and was indefatigable in his efforts for the upliftment of Indian women’ (no author, 1992: n.p.). In 2000–2001 the Indian Economic Association commemorated Naoroji’s 175th birth anniversary with a volume of contributions from more than a score of scholars from across the country, specifically including at least half from southern India. The President of the Association, G. S. Bhalla, noted that Dadabhai’s economic ideas ‘seem to contradict’ the dominant contemporary thrust towards ‘globalization’ (Hajela, 2001: viii). Notes

References

Courtesy: IIC Quarterly, Summer 2025 issue, Volume 52, Number 1, India International Centre, New Delhi. |