Gandhi’s Childhood Memoir Reframes Education as ResistanceThe translator's introduction keeps the book in perspective regarding its contemporary relevance. Ashwinkumar frames this memoir as a counter-narrative to the dominant ideological ambience, particularly the portrayal of Gujarat as a symbol of sectarianism. |

- Daanish Bin Nabi

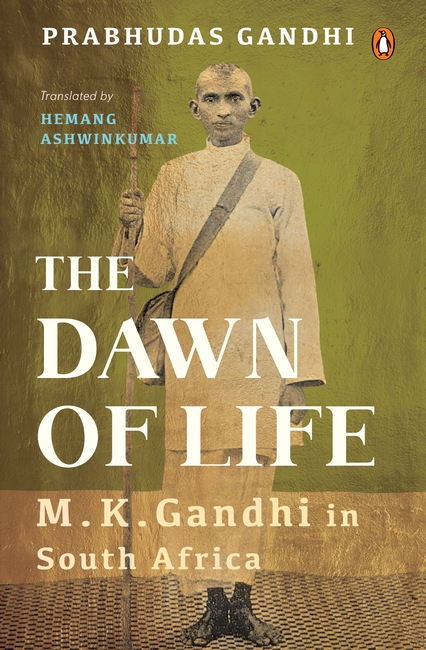

In a literary and historical landscape dominated by big stories and monumental biographies, Prabhudas Gandhi's The Dawn of Life (Penguin Books) is a rare and intimate memoir, reclaiming the personal as political. Translated for the first time into English by Hemang Ashwinkumar and published by Penguin Random House India, this work is not a reminiscence of childhood but an important archival document that captures the formative years of Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy and praxis in South Africa. Originally written in Gujarati and serialized in the handwritten ashram journal Madhpudo in 1923, the memoir offers a textured, first-hand account of life at Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm—spaces that served as laboratories for Gandhi’s experiments in truth, non-violence, and self-reliance. The translator's introduction keeps the book in perspective regarding its contemporary relevance. Ashwinkumar frames this memoir as a counter-narrative to the dominant ideological ambience, particularly the portrayal of Gujarat as a symbol of sectarianism. He says that ashrams, which Gandhi established in South Africa, were crucibles of an alternative vision-one rooted in ahimsa, self-discipline, and spiritual resilience. These were not abstract ideals but lived practices, tested and refined in the daily rhythms of communal life. Thus, the memoir is a valuable archive about the making of the Mahatma, not through hagiography but through the eyes of a child who lived with him. Prabhudas Gandhi, the son of Chhaganlal Gandhi and grandnephew of Mahatma Gandhi, was less than twelve years old during the events he recounts. Yet his observations are anything but juvenile. His prose, laced with humour and humility, captures the texture of ashram life with remarkable clarity. Whether describing the rigors of toilet cleaning, the debates on diet and celibacy, or the rhythms of gardening and manual labor, Prabhudas offers a vivid portrait of a world where the personal was inseparable from the political. His recollections are not only rich in detail but also steeped in the ethical and philosophical undercurrents that defined Gandhian thought. One of the high points of the memoir is its focus on kelavani, or education, which would later be crystallized by Gandhi as Nai Talim in 1937. Ashwinkumar, a teacher himself, calls attention to this feature with particular poignancy in view of how education today is under assault by predictable forces of historiographical revisionism and the suppression of critical thought. By contrast, the ashram schools at Phoenix and Tolstoy Farm were sites of a radical pedagogy: student-centered learning, dignity of physical labor, multilingualism, and an all-round development of body, mind, and spirit. Prabhudas’s reminiscences—the teachers coming with mud-splattered heels and perspiration-drenched shirts—underline the egalitarianism of these institutions. There were no examinations, no rankings, and no fear of failure. Instead, the objective was to create satyagrahis, persons capable of love, resistance, and moral courage. It also comprises rare insights into the life of Maganlal Gandhi, one of the most important associates of the Gandhian movement whose contributions have often been relegated to oblivion. Prabhudas in his writing records the fiery temperament of Maganlal, his struggles with self-control, and his commitment to ideals propagated by Gandhi. The portraits are detailed with affection and honesty, unencumbered with the burden of myth-making. Similarly, the account of Ramdas Gandhi during a prison fast at the age of sixteen is an ideal example of the transformative power of Gandhian education: Ramdas does not force others to join him, yet goes on fast himself, vividly upholding the principle of veerata-bravery rooted in truth. The strength of the memoir lies in how it weaves together the philosophical and the mundane. Discussions of satyagraha, nature cure, and spiritual discipline sit alongside tales of childhood mischief, communal meals, and the challenges of ashram chores. This interplay lends the narrative a rare authenticity. Prabhudas does not shy away from disagreeing with Gandhi on issues such as dietetics or nature cure, and such moments of dissent are treated not as acts of rebellion but as integral to the spirit of inquiry that the ashram fostered. The preface by Prabhudas himself tells the story of how the memoir came to be written. Finding himself short of material for Madhpudo one day, he decided to write about his days in Phoenix Ashram, confident that any story that featured Bapuji would interest the readers. He was right-the serialized pieces were read and passed on by many, and eventually, what Prabhudas calls the Phoenix Purana came into being. So, along with denying any pretensions to autobiography, Prabhudas' intention is to present a simple child's recollection, though here also, he asserts that these are 'experiences' he went through. Yet, it is precisely this modesty that gives power to the memoir. The child's-eye view captures nuances that formal histories often miss-the texture of daily life, the emotional cadences of relationships, the ways in which ideology is lived and internalized. Ashwinkumar's translation is faithful and lyrical, capturing the warmth, wit, and philosophical depth of the original. His introduction places the memoir in the context of broader debates about education, memory, and national identity, and makes a strong case for its continuing relevance. He recounts a telling anecdote from his own classroom in Gujarat, where law students defended the 2020 lockdown, having no idea about its human cost. In response, he invoked the story of Prabhudas Gandhi—a boy who fought alongside his uncle for the rights of indentured labourers in South Africa. The students, unable to read Gujarati, were cut off from this legacy. Thanks to this translation, that gap has now been bridged. The Dawn of Life is more than a memoir; it constitutes a testament to the power of lived experience, ethical education, and moral imagination. In an age that suffers from historical amnesia and ideological distortion, this book acts both as a corrective and a call to conscience. It reminds us that the making of the Mahatma was not a lonely journey but a collective experiment-one that unfolded in the dusty courtyards of ashrams, in the laughter of children, and in the quiet resolve of those who chose truth over comfort. For anyone trying to reach the roots of Gandhian thought, or simply to recapture the moral clarity of a bygone era, the work entitled The Dawn of Life is essential. Courtesy: Brighter Kashmir, dated 4th November, 2025. * Daanish Bin Nabi, Email: daanishinterview@gmail.com |