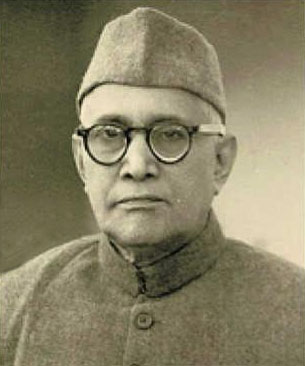

Dr Saifuddin KitchlewThe Forgotten Hero Of Jallianwala Bagh Who Fought For Unity

Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew was a barrister, educationist and a freedom fighter who was at the forefront of the protests against the Rowlatt Act in Amritsar, while devoting his life to preserving communal harmony in India. When the British passed the Rowlatt Act of 1919, Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew became the face of the protests, which saw people across faiths unite against the draconian legislation in Amritsar. In fact, through his life, he stood firmly for the principles of freedom, religious unity, non-violence and a united India undivided along communal lines. A barrister by trade, Dr Kitchlew, alongside fellow freedom fighter Dr Satya Pal, pushed for a hartal/general strike, asking people to suspend businesses and participate in non-violent Satyagraha against their colonial rulers. His appeal for defiance against the act generated real fervour amongst the people of Punjab. In a public gathering on 30 March 1919, where nearly 30,000 gathered, he said, “The message of Mahatma Gandhi has been read to you. All citizens should be prepared for resistance. This does not mean that this sacred town or country should be flooded with blood. The resistance should be a passive one. Do not use harsh words in respect of any policeman or traitor which might cause him pain or lead to the possibility of a breach of peace.” The Rowlatt Act, passed by the Imperial Legislative Council, empowered the colonial administration to censor the press at will, arrest people without warrants and detain them without evidence. During the course of protests, both Dr Kitchlew and Dr Satya Pal had fostered a spirit of religious unity among the Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs of Amritsar. There were chants of ‘Kitchlew ji ki jai’ and ‘Satyapal ji ki jai’ during an anti-government procession through the heart of Amritsar on 9 April 1919, where people from different religious communities came together to celebrate Ramnavami. In his poem ‘Khooni Vaisakhi’, Punjabi poet Nanak Singh, who witnessed these events first hand in Amritsar including the Jallianwala Bagh massacre days later, references how Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs were celebrating the same festival together, how they were drinking water out of the same cup and eating food off the same plate. He goes on to describe the funeral processions after the massacre and how Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs walked side by side. These Ramnavami celebrations showed the populace of Amritsar that if these communities were to overcome their differences, challenging British rule wouldn’t be such a daunting proposition. Witnessing the rise of communal harmony and growing disenchantment against the imposition of the Rowlatt Act compelled the British to arrest Kitchlew and Satya Pal on 10 April, sending them to Dharamshala. It was their arrest that triggered a mass gathering at Jallianwala Bagh comprising Hindu, Sikh and Muslim protestors. In a bid to “disperse” this gathering, General Reginald Dyer and his soldiers massacred hundreds of protestors on 13 April 1919, an event popularly known today as the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. Dr Kitchlew was eventually released from prison in December 1919. FZ Kitchlew, Dr Kitchlew’s grandson, writes in his book Freedom Fighter — The Story of Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, about the day his grandfather was released. “As soon as Kitchlew came out of the prison, a huge crowd gathered in Amritsar and took a historic procession through the city carrying Kitchlew on their shoulders.” Cry for freedomBorn on 15 January 1888 to a Kashmiri businessman, Azizuddin Kitchlew and his wife Dan Bibi in Amritsar, Punjab, Dr Kitchlew grew up in relative privilege. His father owned a business, which traded embroidered pashmina shawls and saffron. Studying in Cambridge University in the United Kingdom before obtaining a PhD from a German university, Dr Kitchlew returned to Amritsar after his studies to practice law. But it was during his Cambridge days that he began developing a genuine consciousness for the many issues India faced under colonial rule. He even joined the Majlis, a debating club in Cambridge, where Indian students came together to discuss the many ills of British rule. It was through this debating club where he met fellow freedom fighters and future prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. As FZ Kitchlew writes, “It was at Cambridge where certain socialistic ideas of Kitchlew were developed… He had always been fascinated by the French Revolution. He read books on these themes, which excited in him a kind of admiration for nationalism and freedom movements.” Upon his return to India, he was deeply influenced by MK Gandhi and the burgeoning freedom struggle, for which he would end up giving up his legal practice. For Communal HarmonyBesides his extensive participation in the freedom struggle, Kithchlew also played an integral role in the Khilafat Movement. Appointed as chief of the All India Khilafat Committee, he began driving home the ideal of pan-Islamism, which wanted all Muslims in India to recognise The Caliph of Turkey as their leader. But once Turkey built a government along secular lines, the movement collapsed in India, and following this, communal riots broke out all over the country. Acknowledging the fallout of the Khilafat Movement, Kitchlew once again entirely committed himself to the cause of nationalism driven by the religious utility in a time when communal disharmony was rearing its ugly head. He understood that if India were to overcome colonial rule, it could only happen if Hindus, Muslims and people of other faiths came together. But the collapse of the Khilafat Movement would fuel the Muslim League’s disenchantment with the Indian National Congress, and their desire for a partition of India along religious lines. A proponent of Poorna Swaraj, Dr Kitchlew was the chairman of the reception committee of the Indian National Congress session in Lahore, where on 26 January 1930 they declared total independence from the British (Poorna Swaraj). This declaration would later go on to lay the groundwork for the Civil Disobedience Movement and the freedom struggle moving forward. As FZ Kitchlew writes, “He was of the opinion that Indian freedom could only be attained through India’s own efforts. According to him, the history of nations that have attained their freedom tells us that self-reliance, self-sacrifice and suffering are the only roads to freedom.” And this “road to freedom” could only be achieved by one nation not divided along communal lines. This is why he was strongly opposed to Partition and felt that such a step would only harm the Muslim cause both politically and economically. He called Partition a blatant “surrender of nationalism for communalism”. Nonetheless, when communal tensions were at their peak during Partition, Dr Kitchlew would play an active role in diffusing them whenever and wherever he could. He even paid a steep price for this cause. When other Muslims left for Pakistan, he refused and decided to stay back in Amritsar. But in 1947 rioters burned down his four-storey home and the family-owned Kitchlew Hosiery Factory in the city, and he was forced to relocate his family to Delhi. A few years after Partition and Independence, he left the Indian National Congress and began developing closer ties with the Communist Party of India. He spent the last years in Delhi establishing closer ties between the Indian government and the USSR. For his efforts, the USSR presented him with the Stalin Peace Prize (subsequently called Lenin Peace Prize) in 1952, while the Government of India included him in the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial trust as well. Besides his impressive work in the Indian freedom struggle, for which he spent a cumulative 14 years in prison, he was also an educationist, playing a stellar role in the founding of the Jamia Millia Islamia University. Given his sympathies for left-wing causes, he was also among the few prominent Congressmen to issue their support for the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, an organisation founded by the legendary freedom fighter Bhagat Singh in 1926. He eventually passed away on 9 October 1963. Following his death, Nehru said, “I have lost a very dear friend who was a brave and steadfast captain in the struggle for India’s freedom.” Till his death, he remained true to his principles and committed to a united India. Courtesy: The Better India, dt. 20.10.2021 |