The Salt March and Political Power |

- By Philip Watkins*AbstractThis paper explores the vision of Gandhi, one most important leaders of the 20th Century, from a theoretical perspective. According to Gandhi, rulers cannot have power without consent of their subjects. Nonviolent movements of civil disobedience, such as the famous Salt March, are manifestations of the power that can be best interpreted considering the theory of pluralistic dependency, addressing the legitimate origins of power and power contestation. Introduction

For Decades we have all come to admire historical nonviolent social movements and the leaders that led them. As Ameri-cans we too have been in struggles of in-justice and foreign control. Perhaps it is our history of being under colonial rule that has given us an especially gained lik-ing of Gandhi and his vision for an inde-pendent India, much like our vision of an independent America from British rule. Unfortunately our admiration for Gandhi does not lead us into a deeper understand-ing of his philosophy. We also have little or no idea about the methodology of non-violence that Gandhi implemented and the theories behind it. If we are to move beyond mere admiration it is very important for us to study the actual campaigns that Gandhi led. The most important campaign of non-violent civil disobedience in India was the salt march. The salt march was a monu-mental move on India’s road to Independ-ence that needs to be analyzed and com-prehended. We can also analyze the salt march through the pluralistic dependency theory to understand how and why it changed India and what ideas stand behind those changes. Leading up to our analysis of the salt march with the pluralistic dependency theory, we must follow a number of im-portant questions. How did the British gain control over India? How did Gandhi become a potent political force in India? What were the salt tax and the salt march? Where did Gandhi’s inspiration come from? British Power in India“The British have not taken India; we have given it to them,” Gandhi wrote in 1906. “They are not in India because of their strength, but because we keep them.” (Ac-kerman & Duvall, 2000, p. 68). The Brit-ish colonization of India was certainly dif-ferent from the colonization of the Ameri-cas. In fact colonization was not the first intention of the British. But, as Gandhi observed in 1906 the British were handed India by its own people. This allowed the British to claim India as their jewel to the East. Before we can go into Gandhi’s second movement of nonviolent civil dis-obedience, we must first gain an under-standing of how the British gained control over India. The British were first involved with India as traders. They came to India in the sixteenth century to set up stations of trade and military along the coast. Fur-ther inland were the Muslim Meghal em-perors who had inhabited the interior of India since the invasion of their ancestors from central Asia. The peace amongst tribes ended in the eighteenth century when they desired more power and influ-ence over the land. The fighting decreased trade and put the East India Company’s monopoly over trade with India at risk. To continue trade and protect its interest, the East India Company accumulated an army in 1765. With an army at full force the East India Company proceeded to take over Bengal, Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay. With the East India Company’s territories set in place it soon realized that governing all of India was an impossible task. In order to make governing easier the East India Company made treaties with influential Indian dynasties in exchange for military protection. British control began to take root. When the East India Company fi-nally dissolved, The British government took control over India making it an offi-cial colony. The process which the gov-ernment used to control India was identi-cal to the strategy the East India Company set forth years before. British officials would continue to give money and incen-tives to powerful Indians who would in return stay loyal to the British and con-tinue to push policies that would benefit British Interest. “The Raj” which was the name for British control over India had begun. The Rise of GandhiAs a young man Gandhi studied law in London and eventually set up a practice in Bombay. His success In Bombay was waning so he took up an offer from a businessman who sent Gandhi to South Africa to do some legal work. While in South Africa Gandhi was recognized as the only Indian lawyer in the country and he thus came to be the leader of the Indian minority in South Africa. Gandhi then dove into using civil disobedience against the unjust and discriminatory laws toward Indians in South Africa. Gandhi set up small campaigns that gave him national notoriety (Hermann & Rothermund 1998: p. 265). In 1915 Gandhi returned to India with reverence from mostly Indian nation-alists. Gandhi was unsure what it was he wanted to do in India. In fact, he had be-come very detached from India by his time spent in London and South Africa. Gandhi decided to take a one-year train tour of India to get a feel for the people and their surroundings. After the tour Gandhi was able and confident in starting small local campaigns. These small campaigns gave Gan-dhi a good following and forced the Indian Congress to take notice. Eventually Gan-dhi became involved with the Indian Con-gress and became a strong political force in their meetings. When tension grew be-tween the British and the Indian Congress, the Congress turned to Gandhi to head a new civil disobedience campaign. Gandhi knew exactly where he should focus this new campaign, the salt tax.

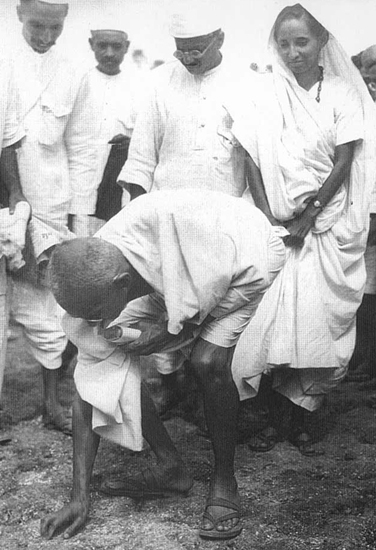

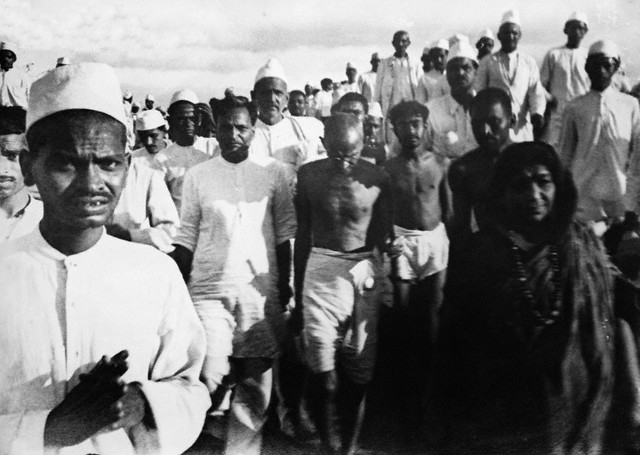

Taxes and the Salt MarchIn 1765 The East India Company set up manufacturing monopolies over salt, to-bacco, and betel nuts. The British took over these monopolies, which imposed their control over the Indian market. With the monopolies in place, the British also applied a tax on the sale of salt, tobacco, and betel nuts as well. The salt tax was especially devastating due to the fact that salt was a staple food for Indians. (Read, and Fisher, 1997). The salt tax hurt eve-ryone especially Indians from the lower class. Even the poorest laborer could not gather salt without paying exorbitant taxes. (Weber, 2002). The salt tax was blatantly inequitable and unfair for the Indian people. To start the movement Gandhi de-cided to send a letter to the Viceroy of In-dian, Lord Irwin demanding him to relin-quish the salt tax. If Irwin did not except Gandhi’s demands, then he would push the movement toward civil disobedience. Gandhi made plans to leave Ahmedabad and march for three weeks until he ended at the city of Dandi. While in Dandi, Gan-dhi and his followers were to go to the sea and collect salt In defiance of the salt tax and monopoly. Gandhi’s reasons for choosing the salt march as the first civil disobedience were strategic and well thought out. For one, he wanted to get the poor, the Mus-lims, and the Hindu’s to come together in unity to fight a common injustice that they have all dealt with. Second, the salt tax was not a large piece of revenue for the British, meaning that the British would not use an extreme amount of force against the march. This in affect would lower the level of fear amongst Indians and enable more people to participate in the cause. And thirdly the salt tax was symbolic, in that it portrayed the British unjust colonial rule over everything including the simple everyday lives of Indians. The salt march therefore would increase Indian morale and give them a sense of power and self-respect that was virtually non-existent for decades. When the plans were all set in place Gandhi took the first step on March 2nd by asking the viceroy of India, Lord Irwin, to accept the demands or face civil disobedience. Irwin would not compro-mise to the demands. Gandhi stayed true to his words and gathered seventy of his followers who were well disciplined in nonviolence and began to march toward Dandi. The marchers were greeted in each passing town and city with great cheers and excitement. In every town Gandhi would take the opportunity to speak to the people about the injustice of the salt tax and he would encourage everyone to join the marchers and boycott all British made goods. In the morning of April 6 twelve thousand marchers gathered around the shore waiting for Gandhi to give the signal to collect salt. When the marchers were ready Gandhi raised up a handful of sand signifying the end of the salt monopoly and the beginning of civil disobedience. The news spread all over the country and nearly every town especially those on the coast reported people making salt. (Ac-kerman, and Duvall, 2000, p. 87). Nationalism and the cry for inde-pendence were at an all time high during the salt march and the other actions that followed. It is true that the salt march had very little significance to the British, but it was arguably the most significant action for the Indians. The salt march was the first firm step to a paradigm change in po-litical power for the Indians. Gandhi was the catalyst to this paradigm change with his philosophy of nonviolence and social power. Gandhi’s InspirationGandhi was inspired by many different people and movements to create his politi-cal philosophy. Perhaps the most influen-tial philosopher on civil disobedience for Gandhi was Henry David Thoreau. Tho-reau had written an essay titled “Civil Disobedience” in which he explains that if the government imposes unjust laws then it is the duty of the people to “withdraw all support both in person and property” (Thoreau, 1993, p. 8) of the government and cease to abide by the laws labeled as unjust. Gandhi adopted ideas such as these in his philosophy of nonviolence. Martin Luther King, Jr. and César Chávez then adopted Gandhi’s philosophy in order to combat the injustices that they faced. There are some differences with each leader’s philosophy of nonviolence and the use of civil disobedience. But, one idea remains constant through out all movements of nonviolent civil disobedi-ence, and that is the idea of political power. The question that every social movement raises is, “who wields the po-litical power?” And the answer always remains unchanged, “The people hold the power.” The Two Theories of Political Power According to Gene SharpUltimately there are two theories of politi-cal power to choose from. The most com-mon One is the “Monolith Theory” which states, that people are dependent upon the government or ruler, which wields all po-litical power. The second is the “Plural-istic Dependency Theory” which states that the government or rulers power is de-pendent upon the people’s consent. The sources of power that a government or ruler has comes from perception of author-ity, human resources, skills and knowl-edge of cabinets or loyalists, the subjects’ absence of common goal or self worth, control of material resources, and ability to use sanctions. Sharp (1973) argues that the Monolith Theory is “factually not true” (p. 9). In order for the government or ruler to wield power they must draw it from the sources of power mentioned above. Every one of those sources is dependent upon the consent and obedience of the people. For example, sanctions, which are arguably the most devastating source of power, de-pend upon the military or police to obey the orders of the ruler or government. If the military ceases to obey, then the ruler cannot inflict power through sanctions. The amount of power a ruler may have depends on the degree of influence the ruler has over every power source. Though, every power source is ultimately external from the ruler himself. The Pluralistic Dependency The-ory is a more accurate assumption of po-litical power. If the people disregard the ruler then essentially the ruler has no one to rule leaving him or her powerless. As mentioned before a government’s power will not function without the obedience and consent of the subjects. So why is it that people obey the government or ruler even when unjust laws or actions are im-posed? There are many complex reasons for different people; here are some: habit of obedience, fear of sanctions, morally obligated to obey, incentives (self-interest), psychological or personal identi-fication with a ruler, ignorance, and lack of self respect among subjects. It is impor-tant to note that though obedience is often practiced it is not involuntary, and the whole population at any given time does not completely obey the government uni-versally. There are always people that ex-ercise disobedience more often than others. Pluralistic Dependency Theory Applied to the Salt March“Some conflicts do not yield to compro-mise and can be resolved only through struggle. Conflicts which, in one way or another, involve the fundamental princi-ples of society, of independence, of self-respect, or of people’s capacity to deter-mine their own future are such conflicts” (Sharp, 1973, p. 3) With this sort of con-flict it is inherent to have a concept of po-litical power, which in turn decides how you intend to struggle for that power. The Monolith Theory is associated with violent action because if the ruler is the only one with power then the only resolution is to kill him and his loyalists. Nonviolent ac-tion bases its concept of political power on the Pluralistic Dependency Theory, which gives people the power; they just need to learn to wield it through disobedience. For us to come up with a more in depth understanding of the salt march and civil disobedience in India we need to view the events through the lens of Gene Sharp and his Pluralistic Dependency Theory. To do this a set of questions need to be asked. One: “What sources of power did the British use to control India?” Two: “Why did the Indians obey the British?” Three: “Was there a paradigm shift relat-ing to the Pluralistic Dependency Theory among the people of India?” and four: “Was the Pluralistic Dependency Theory an appropriate assumption and way of looking at political power for Gandhi and his followers?” Sources of PowerThe British use of power and the sources that power came from was extensive. They most certainly had all sources in a firm grip to control the people of India. There are some sources that do stand out during the salt march. Not coincidentally Gandhi planned the salt march around decreasing the British control over those sources of power. The four main sources the salt march attacked were authority, subject’s lack of a common goal, material resources, and ability to use sanctions. The British use of authority was crucial for their control over the Indian people. Authority is defined as the extent that subjects believe in the superiority of the ruler. There were varying degrees of the British extent of authority for every Indian, for example the Indian Congress tried to reform the British government by sending petitions. With the actions of the Congress aside, the authority of the British was almost completely unchallenged up until the salt march. The collective Indian population gave the British a great amount of authority due to their willingness to submit their livelihoods. If anything the salt march really helped change the Indians thinking of Brit-ish authority. The salt march showed the Indians that they don’t have to submit to a law and monopoly that is unjust and det-rimental to their daily lives. Gandhi en-forced the idea that it was the nation’s duty to rise up against the salt tax and dis-obey the British authority over the manu-facturing of salt. The decrease in British authority was evident in the thousands of Indians across the nation who participated in making their own salt. India was divided on many different levels. The divisions came from the large populations of Muslims and Hindus, and the many languages and dialects that created barriers for communication across the nation. Another source of division came from the caste system, which as-signed social status of people at birth. The lowest positions on the caste system were the “untouchables” which literally were not to be touched or even looked at by people of a different caste position. These divisions were a source of power for the British. Without a unified front in India then the oppression of the British could not be attacked with much force. As men-tioned before Gandhi strategically chose the salt tax and monopoly as a cause that would unify all Indians. That is exactly what happened in the salt march. Un-touchables, Muslims, Hindus, and every-one in between marched along side each other to the sea. The salt march did not completely unify the differences among people, in fact some people were disgusted with the presence of untouchables and there was less Muslim support because Gandhi himself was a Hindu. It was not perfect, but there was still an increase in unity among all groups. The British had a large degree of control over material resources. They es-pecially had a lot of influence over the sale and manufacture of salt. The salt march deliberately ignored the British monopoly over salt. The disobedience that occurred during the salt march proved that the mo-nopoly of salt and the salt tax existed only because of the consent of the Indian peo-ple. This consent was thoroughly broken. The British had relied on sanctions if any-one decided to challenge their laws or policies. The salt march had a different affect on the British ability to cast sanctions. The salt march was an act of non-violent disobedience. This placed two dif-ficult decisions upon the British. One de-cision was that they could have imposed sanctions and arrested Gandhi and his fol-lowers, but this would have created mar-tyrs and an up roar across the nation. Or they could not impose any sanctions and allow themselves to look weak. The British chose the latter decision in the case of the salt march. In affect the salt march decreased the British control over sanctions as long as the movement remained nonviolent. Indian ObedienceAll of the reasons for obedience could apply one way or another in the case of India’s obedience to British rule. For one, the British gave powerful Indians incentives to remain loyal. But, only a few reasons for obedience relate to the salt march. The first reason was that it was simple habit to obey the salt tax. The very reason for obedience became the fact that it has always been the habit of the people. No one really questioned this habit until Gandhi showed the injustice of the tax and the need to oppose it. The salt march began the breaking of habits especially those that cause people to obey the British. Two reasons for obedience relating to the salt march are also affected by the sources of power that the British drew from. These two reasons are fear of sanc-tions, and absence of self-confidence among the subjects. The Indians obeyed because they feared the sanctions that could be imposed upon them if they disobeyed. The British always had military and police officers at hand. In the case of the salt march the fear of sanctions dropped because the British decided it would be too costly to use them. The most powerful reason for obedience is the fact that most Indians lacked a sense of self-confidence. Indians were experiencing internalized oppression at a very high degree. Their lack of self-confidence inversely related to the British authority. One of Gandhi’s main goals for the salt march was to instill some sort of self-respect in the Indian people. He believe that if the people had self respect then they would not give into the habit of obedience, fear of sanctions, and authority of the British. The salt march increased self-respect by giving people the chance to stand up for justice in the face of the unjust salt tax and monopoly. A Shift Towards The Pluralistic Dependency TheoryThe salt march directly attacked the sources of power and obedience as mentioned above. In effect the salt march was the first step toward a paradigm shift from the Monolith Theory to the Pluralistic Dependency Theory. With the movement toward Pluralistic Dependency Theory started by the salt march, Indians were able to decrease the sources of power that the British possessed and slowly come to the realization that the those sources of power were solely dependent upon the themselves obeying or disobeying. The evidence for the paradigm shift is in the fact that the Indians even followed through with participating in the salt march. If the Indians believed in the Monolith theory then the salt march would be looked upon as a useless cause. If they were to go forth with the salt march in the perspective of the Monolith theory then the people would destroy the salt factories themselves, and they would use violence as the only way to possess power. ConclusionActing out of violence to gain power for the Indians would have been a bad idea for their situation. If they used violence then there would be nothing unjustified in the British using their military to crush the protesters. The best way of looking at political power for the Indians was with the Pluralistic Dependency Theory. There wasn’t as much risk involved, as with the Monolith theory, all they had to do was withdraw support and obedience, which in affect would decrease the illusion of British power. When studying violent struggle and nonviolent struggle they appear to be very different. And they most certainly are on many levels. But, the differences of the two begin at the fundamental basis of how they view political power. It was my goal for this study of the salt march to get to the root of how they view power to make them struggle and oppose their enemy in a nonviolent way. Gene Sharp and his Pluralistic De-pendency Theory gives an explanation of how the salt march worked and what how the Indians viewed political power. The Pluralistic Dependency theory is not only relevant to the salt march, but it is also relevant to all nonviolent civil disobedient movements. Without the Pluralistic De-pendency Theory nonviolence and civil disobedience would make very little sense. References

Courtesy: Watkins, Philip (2005) The Salt March and Political Power, Culture, Society, and Praxis: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 4. * California State University, Monterey Bay |