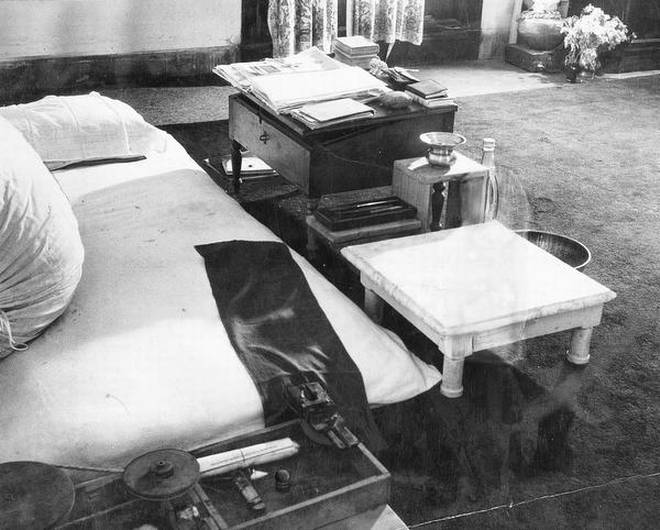

The many conversations with truth: M.K. Gandhi as a writerGandhi was one of the most prolific writers of all times. What did writing mean to him?- by N S Gundur*  Mahatma Gandhi's study room in Birla House, where he spent the last months of his life. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives If M.K. Gandhi’s writings matter to us today, the writer in him should matter more, especially for humanist scholars. He is one of the most prolific writers of all times, having provided enough material for the nearly hundred-volume Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, besides numerous rough drafts and unpublished material. How did Gandhi manage to write so much despite his hectic schedule? Since writing is a public act performed privately, what did writing mean to Gandhi — the public personality and the private self? Why did he write at all? In examining Gandhi’s writerly self, I would like to focus on two of his classics, Hind Swaraj and his autobiography,The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Gandhi’s involvement with print culture — journalism, editing, publishing, translating and authoring books - invites one more biography. His direct and simple prose devoid of artificiality was honed over the years, chiefly through his reading of the Bible and the English authors. His experience of drafting documents constantly for the Congress might have shaped his art of composition too. Besides, he was an obsessive letter-writer, penning thousands of epistles in his lifetime. No rights reservedGandhi wrote Hind Swaraj in Gujarati in 1909, aboard a steamer, when he was on the way to South Africa from England. In their critical edition of Hind Swaraj, Suresh Sharma and Tridip Suhrud reconstruct the history of its composition. The pull of writing was so overwhelming that Gandhi used his left hand when the right got tired. The journey had been preceded by an intense period of thinking, reading and discussion on the issues he dealt with in Hind Swaraj. The steamer, like prison, provided an enabling space to reflect and write. As Gandhi explains in the foreword, he wrote Hind Swaraj because he could not restrain himself after having read and pondered much. He says that the views expressed in the book are not his because they were formed after reading several books. In the appendix he gives a list of books that influenced him. Gandhi conceived of his writing as bricolage, an assemblage of different modes of thought. He weaved in the ideas of Plato, Tolstoy, Ruskin, Thoreau, Edward Carpenter, Dadabhai Naoroji, and many others, in Hind Swaraj. Thus Gandhi not only negated the idea of the author at the centre of the production of meaning, he also practised inter-textuality, predating the poststructuralist theory of the death of the author. He had a pre-modern and pre-capitalist understanding of the writing self and text — for him, they were not sites of intellectual property. He renounced the text by declaring in the title page of the first English edition of Hind Swaraj, ‘No Rights Reserved’. If Gandhi conceived of himself as a weaver of different thoughts in Hind Swaraj, he was up to a different adventure in his autobiography. The critical edition of My Experiments with Truth by Suhrud gives us several clues to what writing meant for Gandhi. According to Suhrud, Gandhi experimented with all kinds of things, including food, clothing and body. Likewise, writing for him was a field of experiments with different practices of the self. Writing, especially the autobiography, was also a matrix of self-discipline. When he found himself stalled, he framed a programme, devoting six hours a day to literary studies as part of his writing exercise. Still small voiceIf he wrote Hind Swaraj in the solitary space of the steamer, he penned most of his autobiography in the social environs of the ashram. Originally written in Gujarati, it came out in 166 instalments in Gandhi’s journal, Navajivan, between 1925 and 1929. When he began, he had no definite plan, no diary or documents on which to base the story. He says, “I write just as the Spirit moves me at the time of writing.” As if as a counterpoint to the polyphony of Hind Swaraj, it is the antarayami (a Gujarati word translated as ‘Spirit’ in English), the inner voice, that speaks in My Experiments. Gandhi was not following fashionable Western practices in writing his autobiography. For him, his life consisted of nothing but his experiments with truth and he wanted to tell that story. He made a clear distinction between atmakatha (the story of a self) and jivan vrutant (the chronicle of life). What he attempted was atmakatha — the autobiography as a space for having a conversation with oneself, a site for self-exploration. Suhrud observes that Gandhi could have written it only in Gujarati, the language in which he communicated with the self and also the language in which he heard the ‘still small voice’ speaking from within. He stopped writing it the moment he thought the latter part of his life was already in the public sphere. Writing for Gandhi was thus both a personal conversation with the self and a social act of communication with the reader outside. And it was through this ethical engagement with the self and the world that he conveyed the principles that he practised all his life. Courtesy: thehindu.com, dt. 03 October, 2020 * The writer is Chairman, Department of English Studies, Davangere University, Karnataka. |