Confronting Empire |

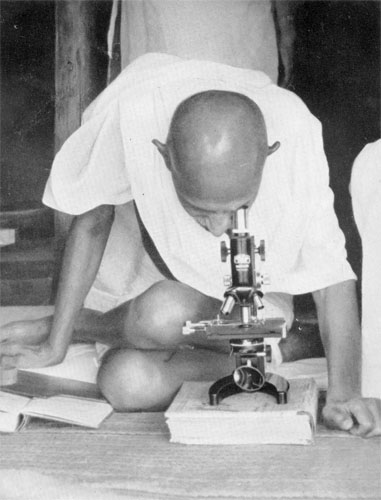

- By Daniel C. Taylor, Carl E. Taylor, Jesse O. TaylorBecome the change you wish to see. Around the world, a variety of forces impinge on communities’ ability to determine their futures. Some of these forces will not compromise, blatantly seeking to plunder resources, exploit people, and rely on obfuscating paperwork or even brutality to advance their self-serving agendas. They intend to take advantage of communities, and have no intention to change. Continuing with the functional nomenclature of SEED-SCALE, these forces can be grouped under the concept of “empire.” Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have argued that such forces include not only military or political infringement by governments in the manner of classical imperialism, but also encroachment by corporations and international bodies, and also development agencies that allegedly avow community empowerment.1 Communities are often rendered complicit in their exploitation, going along because of a variety of compensations. In situations of complicity, little can be done. But at other times communities want to break away, they want to confront. How can they? While SEED-SCALE is primarily a means of seeking social evolution rather than revolution, its principles, and more generally the larger idea of growing empowerment, can be used to confront the oppression and malfeasance of empires. In this context, the example of Mahatma Gandhi continues to be relevant.2 Gandhi’s lesson is often viewed only as an achievement of political independence, but we want to focus not on the end he achieved but the method he used to get there: empowerment. Unlike the freedom movements before him, such as the American, French, Haitian, and Soviet revolutions, Gandhi did not fight the Top-down, but in his use of nonviolence he most certainly used force — the force of human energy. Gandhi used philosophical values that enabled people to take ownership of their future, a process that began with the smallest of actions in people’s own lives. Instead of discarding the Outside-in of British media and religion, he was selective, turning a segment of Britain’s media and religion to his purpose. Building from the energy of individual action, he drew together the collective energies of India to overthrow the imperial yoke. In all, his purpose was swaraj — self-rule. Our family was privileged to be in India during much of the time Gandhi was developing his movement, and to have direct contact with him. As the years have passed since, we keep going back to lessons learned from his movement. The innovations he brought forward become only more timely. And, his innovations of process represent the best means for confronting the new empire that is upon us. Mahatma Gandhi coined the word swaraj (literally “self-rule,” but he translated it as “self-control,” and sometimes “a morality based in truth”) to describe ownership by people in determining their future. To understand the term swaraj in a purely political context impoverishes the concept. Gandhi was in South Africa at the time, and the idea of people rising up for independence through nonviolent action that would later become synonymous with his name was not his initial purpose. His idea was that a small group of people could control their destiny by taking control of the basic functions of life. Colonialism was a condition of loss of control for the Indian community; so, too, were racism, poverty, illiteracy, and illness. It was these issues of holistic advancement that concerned him above and beyond political independence. He wanted to reconfigure an idealized village. Idealized village life became his life organizing social frame, for at the village level colonialism could be confronted, but so could many more oppressions. Later in India as his independence movement started to mature, he held to the belief that political freedom means little when broader well-being does not follow (a point that recent history as borne out in Pyrrhic elections and anticolonial revolutionaries turned repressive autocrats). Good governance begins in (and must be held accountable to) practices that improve lives at the local level. In the beginning, Gandhi simply wanted to improve lives on a marginal piece of land in South Africa. What would grow into a freedom movement for one-fifth of humanity, and inspire many other freedom movements of the twentieth century, began as an intentional community for a few. Years later, in India, when the movement had begun to expand from a community of intellectuals and activists to national scale, Gandhi added a term, gram swaraj: community self-rule (or community-based freedom).3 Gram swaraj generates internal, community-wide, sustaining energy; it remains village focused and promotes a village based on idealized principles. It contains self-correcting direction because it is inspired and regulated by what Gandhi termed “experimenting with truth.” He argued that what brings change to people’s lives comes not from the marketplace or armies, nor from religion or political process, but from the knowledge of reality: truth. For Gandhi, truth must be internalized and adhered to so that it continually corrects action.4 Growing understanding from experimentation thus redefines society from the small to all. (This is much the same process we term Self-Evaluation for Effective Decision Making, SEED.) As revealed in the title of his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth5 freedom grown in this manner is never totally achieved but is always made greater by the truth-centered quest. As John Chathanatt notes, “Like Plato, Gandhi considered the search for Truth to be more important than Truth as such.”6 Gandhi was a thinker of process.  Figure 10.1. Gandhi constantly experimented and searched for truth — and his methods

often caught his associates off-guard. The spinning wheel visibly conveyed this message: freedom through the work of village hands. Each individual turning his or her wheel gave evidence of self-potential. The act of spinning used resources grown in that place (swadeshi, self-sufficiency), locally grown cotton, locally grown wood that made the wheels. What is important is not the practicality of spinning, but the practice of it, as an emblematic action with direct consequences in people’s lives. When people wore khadi (homespun) cloth, they embodied proof that they could take the fabric of life into their own hands (in his words, “become the change you wish to see”). As Gandhi said to news reporters who puzzled over why this man leading a national freedom movement spoke to them from behind a spinning wheel and why he wore homespun clothes, “The song of our spinning wheels is the song of freedom — the freedoms we are making in our own lives.”7 The British Raj relied heavily on pageantry and spectacle to dramatize its power, from crisply ironed whites and pith helmets to the grade parades of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, from elephant-back tiger hunts modeled on their Moghul predecessors to Gothic architecture modeled on their own imperial capitol.8 Gandhi was a master of counter-spectacles: from the Salt March, to his numerous hunger strikes, and always back to the spinning wheel — homespun, home-woven, how stark the difference with the pagents of empire. Gandhi was perhaps the first great practitioner of today’s political “photo-op.” Indeed it was arguably the spectacle of nonviolence that made it such an effective political force as is palpable in contemporary media accounts: In eighteen years of reporting in twenty two countries, during which I have witness innumerable civil disturbances, riots, street fights, and rebellions, I have never witnessed such a harrowing scenes as at Dharsana . . . the sight of men advancing coldly and deliberately and submitting to beating without attempting defense. Sometimes the scenes were so painful that I had to turn away momentarily. . . they were so thoroughly imbued with Gandhi’s non-violence creed, and the leaders constantly stood in front of the ranks imploring them to remember that Gandhi’s soul was with them. . . . hundreds of blows inflicted by the police, but saw not a single blow returned by the volunteers . . . [or] even raise his arm to deflect the blows from lathis. There were no outcries from beaten swarajist, only groans after they had submitted to their beating.9 This is power, visible human power, which commands the gaze precisely through being nearly unwatchable. In the above account part of what is so unsettling is how the swarajis subvert the pomp and circumstance of military parades, with their flags, banners, and aestheticization of weaponry as a means to forget the realities of violence.10 Nothing renders the painful reality of violence more starkly than this spectacle of its deliberate refusal. Gandhi well understood the importance of such scenes. For instance, he encouraged people to wear clean white clothes so the dirt and blood of beatings would show on photographs all over the world, mobilizing widespread support though his appeal to the gazes of those distant from the struggle. None of these examples are only symbols or purely aesthetic, however. Instead, Gandhi’s actions present a seamless fusion of the symbolic and the literal so that attempting to disentangle those dynamics becomes an exercise in futility, much the way that Gandhi argued for the inextricability of the body and ethics or political and personal freedom. Nowhere is this more evident than in the product of the villagers’ spinning: khadi. Done collectively, the production of homespun khadi showed that India could weave the warp and woof of a new life, threads of local resources from one direction, massive energy of the people from the other. Khadi was their flag long before it was woven into the official banner of the independent nation.11 Wearing this flag of self-reliance as they marched in clothes harvested from their lands and created by their hands, the people were pointing toward a future of their own making. They were marching against empire. Britain had established itself in India first as an economic force, a charter by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600 for the East India Company. It was only when rebellion rose in 1857 that the Crown took explicit political and military governing control. Where the British Empire’s purpose was to feed the growth of the world’s first industrial economy. Gandhi’s purpose was to feed the growth of his country’s capacity. The industrial age factory was a powerful symbol of modernity 100 years ago. In manifest contrast to the power emblemized in belching factories in which human beings become hands attending to vast machines, nonviolent protestors wearing khadi gave proof of the home-grown strength of a turning wheel on a mud floor, evidence of new processes of production from millions of people and tens of thousands of villages. Swaraj of communal making strengthened India with tightly wound new fiber that Gandhi hoped would lead beyond deep forces of oppression: caste, poverty, ignorance, fear of leprosy, and gender discrimination. Today, as military powers send soldiers to distant lands and call them “liberators,” as corporations are freed to plunder the Earth for raw materials and circle the globe for cheap labor, the question must be asked (even if it cannot be answered): what freedom is this? While unseating oppressive regimes and providing jobs do enable freedoms, targeting freedom in the manner pursued by peace-making forces and corporations misses the central tenet that guided Gandhi: truth is in the never-ending journey, and it grows from fealty to principles. Freedom is not given.12 The genuine freedom opened by empowerment grows when people come together to rule themselves, working for mutual benefit. However it is approached, freedom is made by people. Gandhi often reminded his followers that people often find themselves in bondage because they have allowed it to be imposed upon them. This is not to blame the victims for their own oppression, but rather to emphasize that people always have the option to stand up as individuals and join together as communities. Doing so not only liberates those who do, but also creates a momentum that can reach all. It is the way of universal freedom: “If we are to make progress, we must not repeat history but make new history. We must add to the inheritance left by our ancestors.”13 Nothing better illustrates Gandhi’s method of working as an individual within the environment at hand to enable the strength of many than his use of fasting. Self-denial to the point of death for the well-being of others created untenable resonance within British Christian ethics, implicitly evoking to the model of Jesus dying for sinners. It appealed also to the British notion of selfless honor in willingness to die for one’s country, especially in the two decades following the carnage of World War I where the populace hungered for some justification for purposeless death and had begun to question the mythology of empire. And for the people of India, fasting was an act they could relate to, tied as it was to a condition skirted by many every day. Fasting is anchored deep in the Hindu religion: an act of purification, and purification of India was Gandhi’s ultimate objective. In India, announcement of a Gandhian fast was like a bomb, news of which flew across the land even when telegraph lines were denied, communicating a simple message that brought people together: our “great soul” risks his life for us; we must join in solidarity with him.14 Sadly, the momentum Gandhi had started retreated to distant ashrams (study centers) when he was assassinated on January 30, 1948. That week the Mahatma had stepped out in solidarity with the Muslims with whom Hindus and Sikhs had been fighting in the Partition riots. In his talk at evening prayers he had asked others to share their thoughts for how to advance gram swaraj for the poor, the sick, and the marginalized. It was already then obvious to him that what was coming was a new empire, a new Indian elite in control of the levers of production. What was coming was a planned, Top-down economy allegedly in the interests of the people, but, as the next forty years of economic failures would show (the economic model changed in the 1990s), it used economic centralization to augment central political control.15 In Gandhi’s view, the journey for real freedom only began with political independence. His quest was for a freedom that transcended politics, a quest that remains to be achieved. After independence the government that unfolded adopted forms and processes that mirrored the British model, but identification with the people remained symbolic: leaders might wear khadi, but they did not actually spin the thread to make it. They had mistaken khadi for cloth.16 The will of the people was solicited every five years at elections; for the rest of the time, bureaucracy ran the country in the name of the people. Important questions lie here unanswered. How much can a leader achieve against deep social defects, for example Gandhi’s failure to adequately address the caste system? Gandhi is today frequently blamed because he did not “solve” the caste problem. Undeniably he could have done more, but such blaming of earlier leadership also implicates the followers for not carrying on the quest. Continuing social reform comes from on-going action. One generation’s unsuccessful attempt does not relieve the next from trying again. Those who are oppressed by millennia-old discrimination (as the outcastes, dalits, “those who are Untouchable,” continue to be) are apt to blame attempts that do not reach them.17 Gandhi while leading a freedom movement was also holding it together (he failed to hold the Muslims inside it). Could he have held the higher castes in if he had worked harder to lift up the lower castes? The answer is not known. But what is known is that today the opportunity exists to push on. Today, the reality of India is that a new empire is in place, one of continued oppression for the poor, lower castes, women, and tribals. While India now has a surging economy that has transformed life for the upper and middle classes and achieved world-class status in medicine and technology, the country remains home to the diseases of pneumonia, malaria, tuberculosis, dysentery, and leprosy that Gandhi so worried about. The first disease killed his wife; the last afflicted a man living in a hut close to his. Seven hundred million in India are indeed better off, but 300 million still live on the margins, and for them conditions get worse.18 This entrenched exclusion would bother Gandhi. A movement in which enough prosper to lift the overall average, while the abyss of inequity separating 300 million grows ever wider, and is held in place by the violence of political leaders and the police, is a world of empire and legitimized violence. Words of equity go forward, selective statistics that describe progress mount, but persistent inequity rots the foundation of India’s alleged progress; it creates a state not of civilization but of empire. And this rot is endorsed by the international agencies whose mission is to alleviate poverty, illness, and discrimination. How much does the Washington Consensus of today (implemented by people who visit the villages in the day only to return to five-star hotels at night) differ from the crowning of Queen Victoria Empress of India (she never set foot on the subcontinent), or the days when Gandhi saw the mills of England, as the symbol of exploitation? Decisions made in air-conditioned boardrooms have life-or-death consequences in villages the deciders will never see. The promises of aid agencies fade like the dust behind a Land Cruiser speeding back to the capital Gandhi had his faults, but he put the emphasis on the resource that the people had: their energy. As Amartya Sen, whose early research described the potential of equity, argues in his book Development as Freedom, the energy of people has the potential to set them free, expanding capabilities, and giving them the way to choose how to live. Our family went to India a century ago. John and Beth Taylor (Carl’s parents) lived a traveling life through what was then jungle, as medical missionaries. In those days, the family would spend a week in one village, administering medical care, then camp was broken, oxcarts loaded, and off they would go to another cluster of villages. Six to eight weeks later, the oxcarts trundled back to the earlier villages. As the years passed, the mode of transport changed as the oxcart was discarded for Model-T Ford, then a World War II surplus Jeep, but the mode of giving services did not. As John and Beth returned to villages, they brought healing, yet the maladies they treated remained. The deeper realization began to grow that helping people does not help them change the circumstances of their lives. On contrary, it can cause people to wait in villages becoming dependent on such assistance, continuing much as they had been, and taking away their empowerment. In 1947, John and Beth were with Gandhi following the Panipat massacre. After that terrible bloodshed, looking across the crowd in which Hindus had surrounded the Muslims, massacring the fringe and terrifying the rest, Gandhi turned to John and asked if he should start a fast. John’s answer was, “They have suffered enough. Let the Muslims (and Hindus) go their separate ways.” Gandhi did not go on a fast. He had already decided half a year earlier that, in the larger context of creating peace, he must let India and Pakistan, Hindus and Muslims, go their separate ways. What was instructive about this exchange for John was that he could see Gandhi searching, not to relieve the suffering in front of him (as John and Beth, the doctors, had been trying to do), but to find a way by which people who had just been killing each other would reach out to each other, strengthening their relationships in order to create a larger collective context. “We who seek justice will have to do justice for others,” Gandhi had once said, recognizing that the larger context that must replace empire is one of justice.  Figure 10.2. Dr. Beth Taylor caring for refugee patients during the 1947 riots that accompanied the Partition of India and Pakistan. (Photo credit: Henry Ferger) Today in India, the process has advanced of engaging the marginalized. It advanced because people who were marginalized kept pushing for justice. Opportunity for all is codified in the constitution; Babasahib Ambedkar, the leader of the dalits during Gandhi’s time, saw to that. But after the constitution was written, implementation did not follow. High castes and the wealthy remain in power, hiding behind the words, still discriminating in their actions against dalits, women, and those of tribal heritage. But across the half century, using their toe-hold in the constitution and using the ethical framework Gandhi inspired that undergirds modern India, those on the margins kept confronting the new empire, in communities displaced by large dam projects, forcible slum-clearance initiatives, or the struggle for justice such as in Bhopal mentioned in Chapter One.19A In this context, the Gandhian movement of empowerment grew. In 1992 the 73rd amendment to India’s Constitution came into being: panchayati raj (rule by community). 19 One-third of representation in elected bodies is now guaranteed to women, low castes, and tribal peoples. Local governance can now control twenty-three different aspects of budget management. States that have sincerely implemented this amendment (for example, Andhra, Kerala, and Rajasthan) are showing progress. Getting there took four decades after Gandhi’s death and the sympathy generated by the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, Nehru’s grandson, to generate the political pressure to pass the 73rd amendment, but it passed — and that pressure would not have grown if people had not kept pushing.20 A fact omitted in most histories of Gandhi is that after independence he did not want the Congress Party to continue as a political party. He wanted Congress to keep pushing toward sarvodaya (literally translates as “the rise of all,” development of the whole individual as well as community), with political parties being separate. His hope was that the Congress Party would depart politics to focus on the higher goal of social mobilization, and would become a check on government and turn its advocacy for freedom from poverty, caste, ignorance, and discrimination in the new India.21 But Nehru and the others did not go along; they argued if one party stayed in control, there would be constancy in leadership, fitting with their vision of a centrally planned modern state. Whether or not Gandhi’s solutions as he envisioned them are practical for today’s world is not the point. (Indeed, some of them hardly seemed practical in his day.) We bring his mode of social change forward to show that effective solutions against empire come out of never-ending process on evolvinging priorities: people gathering together, fashioning lives in communities, and growing change to scale across a subcontinent. Effective process comes from using procedures as guides for what to do next. A constantly adapting plan defined by time and circumstance enabled Gandhi to stay ahead of the British, who wanted to make their engagement with him into a life-and-death confrontation, a force whom he defied by advocating life for all and that there is “no wealth but life” — a philosophy drawn directly from John Ruskin.22 Gandhi’s complex world was as entangled as any today: confrontations of Hindu and Muslim, caste and outcaste, possible seceding states like Hyderabad and Kashmir, intractable diseases whose true remedies lie not in infections cured with medicines but in social dynamics such as poverty and ignorance. In the years before August 15, 1947, Pax Britannica kept rioters off the streets with the threat of repressive military force. In that era, when Gandhi had needed to find the next step, he retired to his ashram. But as Partition exploded, with the spiraling rise of deaths of three million and the relocation of twenty million people underway, Gandhi had been able to mitigate the violence in Bengal, in part through his fast. His principle-based method had a problem, though. Nonviolent resistance, like violence, requires a foe. With the British quitting India, that principle became almost useless. What was there to non-violently push against? The industries of India were not the foe. Nonviolent action could not be turned against leaders who had just inspired them. As a stand-alone principle, nonviolence was incomplete; like all principles in a complex system it requires other, balancing principles so the process is continually refined so as to be always advancing. There was potential in sarvodaya, but it was not brought forward. Indeed it was undermined, for in the India of 1948 already the socialist-leaning modernization policies of the Nehru government were referring to the people of India as “poor, ill, uneducated, needing services,” a diminishing approach that does not build empowerment. The people of India were no longer being viewed as strong, despite the fact that they had just thrown out the greatest empire the world had then seen. Instead of building from that and coupling it to “experiments for truth” and emphasizing behavior changes (like spinning khadi ) that could be engaged by all, India focused on building its change on scarcities and technologies. The country started down an aid-receiving path that would make the country for the next half-century the largest aid recipient in world history (combining multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental loans and grants). A platform that was in-place of self-reliance was ignored. Dependency was begun. India in 1948 had an alternative base; here it is stated in the context of SEED-SCALE’s four principles.

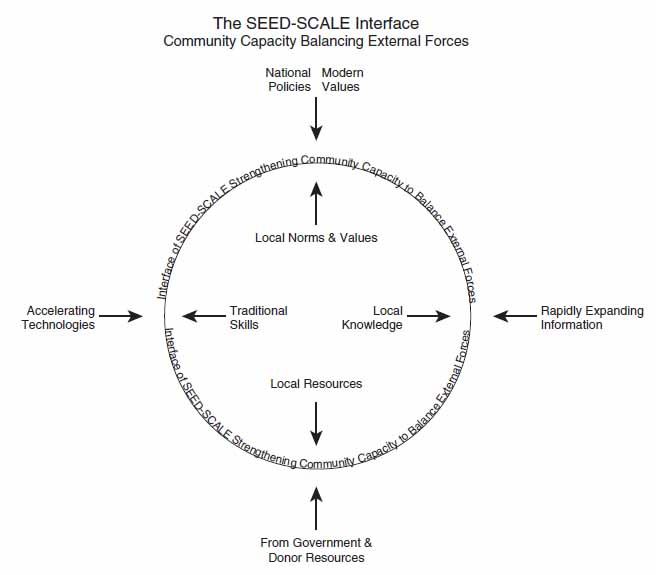

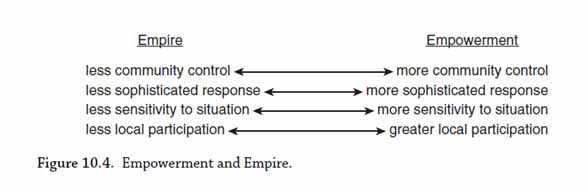

We need an understanding of independence that frees people to determine ways in which they want to live, finding opportunities that fi t their aspirations and allow them to act. Furthermore, new networks of communication allow communities to connect with others. Around the world consciousness grows that such holistic freedom is possible. To grow a nation, locally appropriate solutions must be always evolving. These will come not just by mobilizing the energies of people. In an interlinked socio-econo-biosphere we must also mobilize the economy. In India today, economic growth without engagement of the people, while it produces great wealth, continues to primarily benefit those who already have money and leaves 300 million in absolute poverty and creates a new empire only a level of abstraction removed from colonial empires that saw as legitimate the exploitation of Africa, Asia, and the Americas so long as wealth was growing in the home country. Where the empire Gandhi confronted legitimized racism, this new empire legitimizes poverty, perpetuating a population segment in absolute poverty of the same numerical size as it was a half century ago. Just as America believed for two-thirds of a century that by legitimizing slavery in its constitution it could deny justice, India perpetuates the myth, also for two-thirds of a century, that it has combined Gandhian values with economic growth, a point shown when one hears of the “Gandhian solution.” This cruel joke, or its parallels, is heard often when giving a bribe, for the Mahatma’s image is printed on all rupee notes: “just give a few Gandhis.” Those who placed Gandhi’s picture on the rupee notes may have thought they were honoring the man, but they clearly had forgotten his understanding, emblazoned in a quote hanging on the wall of his simple ashram room: “There is no wealth but life.” Gandhi’s mode of leadership stood in stark contrast to others on the world stage. He was actively working from 1893 to 1948, a time when other major world leaders included Tsar Nicholas II, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Th eodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Kaiser Wilhelm, Adolf Hitler, Chiang Kai-Shek, Mao Zedong, Queen Victoria, and Winston Churchill. Each came to leadership with some version of the premise that the leaders held their positions by strength, and that it was through the exercise of that strength that they could be effective. What sets Gandhi apart is not simply his espousal of nonviolence, but his understanding that power lies in aggregating the individual act. The others above all mobilized their forces and sent them to war. Gandhi mobilized perhaps even more powerful forces and sent them to define a new way forward: as he so wonderfully said, “There go my followers, I’d better hurry and catch up.” What he had to catch up to was one of strongest positive feedback loops of all time. The money he used was modest and the technology minimal. (The wooden spinning wheel could easily have been made more efficient with bearings and better design, but then it could not be made in the villages.) The feedback loop gathered people from all castes, religions, and walks of life, building a tornado that spiraled across the Indian subcontinent, rising in spindrifts of human energy from the villages. Hundreds of satyagrahis (those who followed Gandhi’s path of nonviolence) added their energies, and soon they became tens of thousands. As the whirlwind swept from Gandhi’s Sevagram ashram headquarters, across the Deccan plateau and the Rajasthan desert, tens of millions soon were spinning across the Punjab plains, then the Bengal delta. Against global pressures, both economic and military, seeking to break the principles and instigate even one of these groups into violence, against eff orts to bribe or entice away sectors, against daily realities of poverty and starvation pressing on people to attend to immediate needs, against a host of forces of energy-dissipation, Gandhi grew the whirlwind, teaching it how to grow itself. He drew in the energy of others. He led by example. This was a self-learning, self-assembling system, and that feature allowed it to unravel the complex systems of British politics, economics, and power. Gandhi did not have the plan at the beginning; he evolved it along the way, as to become hundreds of millions participating were also learning. Growing this force was possible because the means were the end; then through the means the end came. Could an organized command-and-control model have brought together such force? A command-control mode would have splintered, or it would have succeeded through a bloodbath.23 Ultimately, Gandhi lost the movement’s focus. Even if he had not been assassinated, he would likely have been marginalized from the political process in a year or two, probably returning to his ashram. But, as a continuing message, the achievements of this man prove it is possible to grow a system of adaptive change using little more than the energies of people applied to grow using process. Rima’s movement of women and men on the Bameng Ridge is tiny, the example in Palin that was ten times larger, are also clusters of such energies that move toward the holistic rise of all ( sarvodaya ). People’s energies and economics now work together, and while people in these examples too often act selfishly, theirs is a process of learning by people, not one of giving to them. A similar lesson comes from the rough-and-tumble settlement of Kabul; they do not know where they are going, but they are learning how as they go. The same is true for the communities at the base of Mount Everest, and they do so within the confines of Communist Party rule. Collectively, what the examples in this book present is an opportunity for all to join. The political framework is not what is important, nor the starting levels of poverty or strife. The question that starts the process is whether we are going to be controlled by empire or whether we are going to mobilize to meet the challenges of our unstable planet.  Figure 10.3. External and internal forces. It is not really a choice. The feedback loop of growing human energies must integrate with the feedback loop of economic growth that has dominated development thinking for so long. The latter we cannot (and do not want to) wish away with, but we must recognize that economic growth is an approximation of the real dynamics underway, rather than an end it itself. The graphic below (Figure 10.3) points to the balances needed: accelerating technologies with traditional skills; local resources with donor resources; indigenous knowledge with new knowledge in the Information Age; and old social norms with the new policy, values, and globalization environment. A constructive dialectic among these nurtures the balance and grows gram swaraj, or community empowerment. “Empire” and “Empowerment” are not either/or states to choose between. It is more accurate to present them as ends along a continuum, where a variety of dynamics tug and pull communities toward these ends. The concern should not be location on the continuum but where the whole continuum is going: toward empire or toward empowerment. In this tug and pull, as local control, response sophistication, locale sensitivity, and people’s participation increase, the energy within the system, empowerment, rises. Higher empowerment has higher human energy. For empowerment to rise, each new achievement is assessed in relation to past performance and collective experience, there by feeding the feedback loop. Communities set the standards for themselves. The process being measured differs from those in an empire, where human energy is constrained because the measures of change are of products that by their nature are available to only a few. When measures of change are exclusionary, the society takes on those characteristics as well. The following pairings (Figure 10.4 ) outline the tug and pull:  A spinning wheel going around suggests same-cycle repetition, but in fact the wheel pulls out a constantly changing cluster of strands, ordering what had been a confused clump. Each handful straightens a complex tangle; as fingers feed in fibers in the circling process, and from that adapting of earlier confusion grows a thread entwined with others comes forth the clothes of life. The iterative process does not repeat but reshapes new life off the wheel of change. In his teaching at evening prayers, Gandhi was explicit in saying how learning to spin was at first clumsy, but with iteration upon iteration, the threads would grow long and strong. It is important to realize that the continuum for one society does not transfer to others. Societies are not ahead or behind one another, for they do not develop along a single line called “development.” Each society moves on its own continuing line, having achieved its place at any particular time by doing the best it could, sometimes against nearly insurmountable obstacles. Through the particularities of each of our lives, as Gandhi said when explaining how the way forward was found, perhaps remembering an African proverb he may have heard decades before, “We make our path by walking it.”24 How to walk forward together? (The White Mountain Apache, when we were teaching them SEED-SCALE, translated the idea “as our community walking forward together.”) No community is “developed,” all are developing; and the cohesion comes through walking forward together on separate journeys along mutually supportive paths running in myriad directions. It is here that the arrow of time in not allowing movement backward, moves us always forward, but are we going forward with constantly improving process? Effective, progress is evaluated against itself, then movement retargeted. As aspirations evolve, so must actions. This adaptation, as it builds capacity within local context, is what drives that community’s direction from the “empire” side of control to empowered local energies. Einstein’s equation E = MC 2 offers an apt means to describe the powerful growth of these energies: human energy equals what matters taken to an exponential scale. While the socio-econo-biosphere may be complicated, what matters is not complicated: to people it is whether their lives are getting better, and that matters a lot. Massive energy can be generated when people produce a little that matters to them. Other people then rush to join in. It is the direction unfolding that matters, and whether that matters to the larger whole. When people see direction as going their way, they press on. The communities in Arunachal Pradesh, Afghanistan, Tibet/China, and New York City, are each in very different conditions, but all are gathering their energies, investing what they possess. What they share is that process. To guide action into the future, it is useful to return to an injunction from Gandhi, lokniti , “people-centered polity.” (Lok means “people,” niti means “ethics/policy guideline.”) Lokniti offered participatory governance based on ethics. The Outside-in and Top-down were partners to serve the people. While Gandhi’s insight on this was great, his specifics were impractical. Khadi cloth is comfortable in the hot Indian climate, but it is not particularly durable. His health ideas, grounded in philosophical traditions rather than science, were not a reliable way to wellness. Nonetheless, despite a near absence of utility, lokniti and satyagraha (“truth force”) brought control into people’s hands, and that is the starting point. A spinning wheel, the great Salt March to the Sea, people sitting down before the police: collectively these actions grounded in ethics changed their conditions of their lives. In lokniti applied at national scale, the answer is not deregulation. Going local does not mean letting go, in the manner of Ronald Reagan or Margaret Thatcher, by taking away the appropriate role for the Top-down in creating an enabling environment and structures to protect equity. Government regulations are one of the comparatively few ways the will of the people can challenge empire that without such checking will happily run roughshod over communities. The great insight of Gandhi (and of Deng Xiaoping, as described in the previous chapter with promoting local economic experimentation in the special zones) was to move the locus of action to the people, allowing them to grow solutions that take advantage of their specific position within the constantly changing socio-econo-biosphere. Moving the focus to process rather than politics will be hard for many to absorb, but actually this recognition opens a wonderful range of opportunities in a world of rising dogma. We live now on an interconnected planet where every community connects to global systems. As communities have the potential learn from one another, capacity and options advance; the learning occurs through feedback loops. This is a larger frame of the community growth process of increasing returns described by economist Brian Arthur, drawing on complexity theory.25 Positive feedback loops are like investing money and getting interest that continues to compound. Moreover, since nested beside and inside one process are multiple feedback loops, returns not only come to the individual worker but accrue to all. As the spinning wheel is emblematic of Gandhi’s process, so the computer might be for today’s social change. But unlike the spinning wheel that served as a symbol for simple village life, the modern machine reflects the multitasking complex modern world. Before computers, machines worked separately: the adding machine, typewriter, slide projector, mailbox, appointment book, clock, and reference library. But when a shared operating system was provided, one machine could engage many functions simultaneously, and each in much more complex ways: spreadsheet analysis, word processing, PowerPoint, email, scheduling, and information access through search engines. Furthermore, a multitasking machine enabled the great, interconnected hive-mind that is the Internet. Through this metaphor we can conceive the needed simultaneous multiple functions at community level. Where before it was believed that community processes had to be separated (health, education, income generation, food production, and security through separated services), using an integrated system that works upwards from the bottom (as the examples in this book indicate), communities can gather all functions into synergy and more effectively engage the Top-down services. This is not a revolution of the community taking over, but growing of partnership through engaging the base of community resources. The currency used in this social operating system is human energy, and directing output is the workplan. And if workplans are written with open code, others can rewrite them to fi t their needs. Additionally, as with cloud computing where the operating system moves outside the machine to a shared but nebulous global service even greater integration becomes possible while retaining local specificity and keeping effective interdependent globalization. Similarly, Gandhi’s understanding of spectacle and the power of communication networks is relevant for the new era. As the revolutions of the “Arab Spring” showed, new technologies provide a way for communities to coalesce in cyberspace only to burst forth with material force into the streets as images are uploaded to distribute evidence of action or atrocities. Pacé Naomi Klein, logos and brands are not merely tools of corporate power but also avenues for resistance because a brand is something that a company must defend, and thus becomes something to which they may be held accountable.26A Greenwashing (and related issues pertaining to social justice) is a genuine problem, but it is also evidence of companies’ need to protect their public image. Just as Gandhi’s appeal to the eyes of the world to witness the lathis (sticks) bloodying bodies in white khadi , today’s communities can appeal to a global gaze starting through billions of screens to assert their presence on the world stage. In today’s age of information overload, pummeling people with falsehoods, facts, and trivia, experiments with truth are perhaps even more needed than in Gandhi’s time. Equally essential is to recognize that there are different truths and they must live together. Truth, as used by Gandhi in his iterative experimental searching, was not usually black or white, truth or falsehood, but a process to work out nuance amid the flood of facts. In this quest for discernment, a distinguishing line needs to be drawn between zeal and the mobilization achieved by empowerment. Zeal zeros in from fundamentalisms to exclusiveness. Empowerment opens up space to engage the energies of all. In such searching, insights from Gandhi’s lifetime of prayer, fasting, jail sentences, speeches, unending spinning, and odd dietary practices do not represent the logical method. But at the center of this process, amid swirls of compromise and expediency, was his compulsion to avoid violence. Nonviolence could easily be misunderstood as passive, but it was anything but inaction. However within his use of nonviolence can be seen an important behavioral feature often overlooked: the imperative of listening (whereas in violence it is hard to listen). There was something about the openness created by his espousal of nonviolence that led people to talk to Gandhi: British colonials, rajas, tycoons, reporters, and most important, the destitute. In listening to their confusion he gave back principles, with the result that relationships were strengthened. Nonviolence, while zealous in its application also created openness to the positions of others. Many people have tried to return to Gandhi’s vision of nonviolence. This great man used that tool and achieved a success from it that is so captivating it is easy to become focused on him and the tool and to miss the meaning of the process he was walking toward. He was a Mahatma (great soul), but, like every human who lacks infallible divine insight, what he saw (and what we all must learn) is the pre-eminence of process: learning from experimenting with truth. The integrity of experimenting with truth is today particularly valid, and we now know more clearly how to engage that. It allows us to constantly update process to the new age, the resulting evidence (not the past) becomes determinative; it portrays what is true in what context, a dynamic of balance, where when one principle acts, others are also acting, correcting potential errors produced by the first. In that journey, Gandhi brought one further important trait: perseverance. Going forward together, experimenting, learning how to learn in complex systems, we gather further understanding about process. The knowledge we have now of the process is more than enough to work with, a process vastly more sophisticated than what Gandhi brought from South Africa that set one-fifth of humanity free. It worked then at a moment of history when humanity waited on the cusp of economic growth. Process is what social development is, and it allows seeds of human energy to achieve global change. The process of people getting to work toward all their aspirations creates the wealth of life. It is time to gather our energies collectively and get to work. Here again comes that phrase of Bapu’s: 26 “There go my followers. I’d better hurry and catch up.” Courtesy: Empowerment on an Unstable Planet: From Seeds of Human Energy to a Scale of Global Change, "Confronting Empire" Chapter 10. Daniel C. Taylor, Carl E. Taylor, Jesse O. Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012) | Email: daniel@future.edu |