Mahatma Gandhi: A Lasting Legacy |

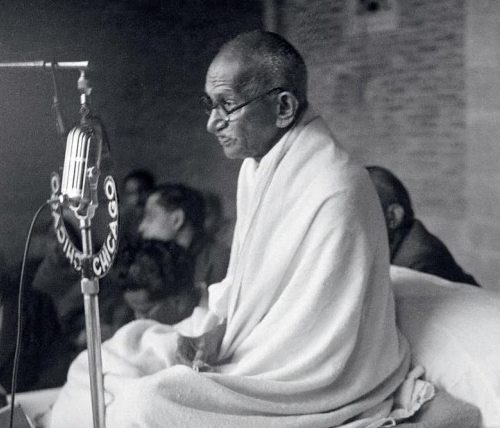

Bhikhu Parekh* Lost in thought A pensive Gandhi, in 1947. (Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy) As we celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, it is worth recalling the frequently ignored scale of his achievements. He was the first Indian to put India on a global map and the only one to be known throughout the world. He was the first Indian to make his political mark outside the country before doing so in India. He has been the greatest mass mobiliser in Indian history, having brought millions of men, and especially women, into public life. He so dominated Indian politics for a quarter of a century that anyone incurring his wrath invited political suicide. He is the only Indian, indeed world, leader to touch life at many different levels and have something to say about each of them, whether it was hygiene, sanitation, bringing up children, morality, sexuality, religion, the economy or high politics. At India's independence, for which he had striven so hard, Gandhi felt so tormented by the pervasive violence that he declined to unfurl the national flag and even to send a message. He refused to accept a political position for himself, and devoted the final two years of his life to healing the wounds of intercommunal violence. He undertook fasts even when his body could no longer tolerate them, walked alone through the thorny streets of Noakhali villages, and urged the victims to show forgiveness. Although repeatedly threatened with violence, he dismissed all offers of security, and dared, even invited, his detractors to do their worst, which one of them did. Although Gandhi had his limitations, there are several areas where he is enormously instructive and which mark him out as one of the greatest men of the 20th century. Gandhi suffered from oppression and injustice most of his adult life. In South Africa, he was thrown out of a train on a cold night for daring to travel first-class, was dragged down from a coach by a swearing conductor and only just saved by his fellow passengers, and kicked into the gutter by a sentry for daring to walk past President Kruger's house in Pretoria. In Transvaal, he was arrested for protesting against the Registration Act of 1900 and kept in a cell with common criminals who made sexual overtures and carried on indecent activities in his presence. He was stoned and kicked by a racist white mob in Durban, and escaped lynching only because of the sanctuary of a nearby police station, which he was later able to leave disguised as a policeman. Gandhi reflected deeply on these and other experi-ences and asked why oppression occurred, how, and what the role of the victim was. He concluded that the victims of oppression were never innocent. In fact, they were complicit in their own oppression. The British ruled India with the help of Indians. In the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, it was Indian soldiers who fired on their fellow Indians. Gandhi went further and argued that all power ultimately came from the victim's cooperation without which it remains hollow. Since ordinary men and women enjoyed this kind of power, what they needed for their liberation was the courage to assert it and deny their masters their cooperation. Most of them were too nervous or afraid to do this. Rebuking Indians in South Africa, Gandhi said that those who behave like worms should not blame others for trampling on them. And again, in another context, he asked Indians to learn to 'rebel against themselves'. Courage, for Gandhi, was bound up with self-respect and a great human virtue. His concern all his life was to appeal to the self-respect of the victims of injustice. As Nehru said, his greatest contribution was to remove the pall of fear that had gripped India and empower its frightened and diffident people. Another area where Gandhi had profound things to say relates to his practice of ahimsa. For him, it was wrongly understood as not causing harm. If an animal was dying of an interminable disease and had only a few hours left to live, it was an act of love to end its life with a fatal injection. It involved violence, but was not a violent act. As Gandhi once said, not 'non-violence' but 'compassion' or 'love' was the correct English translation of ahimsa. There are also several other respects in which Gandhi stretched and deepened the concept of ahimsa. In the Indian traditions, harm is defined widely to include not only physical but also psychological, moral and other forms of pida or klesa (pain). Gandhi not only accepted this broad definition, but stretched it further. In his view, one might harm or kill a man by shooting him or by denying him the basic necessities of life over a period of time. Whether one killed him 'at a stroke' or 'by inches', the result was the same, and the individual involved was guilty of violence. Insulting, demeaning or humiliating others, diminishing their self-respect, speaking harsh words, passing harsh judgements, anger and mental cruelty were also forms of harm. Gandhi's idea of ahimsa was the basis of the practice of Satyagraha, involving transforming others through one's suffering. He called it a 'surgery of the soul'. A satyagrahi took his stand on what he considered to be his true or just demand, but kept open the possibility of revising his views in the light of his struggle. He appealed to the better instincts of his opponent, activated his conscience, broadened his mind and heart, and sought his cooperation in looking for and achieving a just resolution. Although Gandhi was a deeply religious man, he could not be more different from a fanatic or a fundamentalist. This was so because he firmly believed that no religion was perfect and that it must subject itself to the test of human reason and experience. It could never be perfect because it was revealed or communicated in a particular language, at a particular point in history, and was subject to a variety of interpretations. Since this was so, every religion deserved respect. It also had much to learn from others, and should therefore approach them in a spirit of humility. Gandhi himself provided an excellent example of this by borrowing freely from other religions, especially Christianity and blending it beautifully with Hinduism. Gandhi's guiding principle was, let noble thoughts come to us from all directions. He wanted to live in a house with walls to protect him but with windows wide open to allow fresh currents of thought. In a profound sense, Gandhi is one of the first theorists and practitioners of multiculturalism or a creative dialogue between cultures. His way of understanding the nature of religion guarded against fanaticism and has great relevance to our troubled world. Gandhi's idea of political leadership is also fascinating and inspirational. As a leader of a national movement, he was extremely conscious of what was expected of a leader and what the limits of his power were. When he felt his non-cooperation movement had gone in a wrong direction and turned violent, he called it a Himalayan blunder and stopped it. It is difficult to think of any leader in history who publi-cly acknowledged his mistake and even tried to rectify it. Gandhi seems to have felt the same way about communal violence, especially between 1946 and 1948. He thought he had perhaps not paid the matter sufficient attention. As someone who tormented himself over the smallest error of judgement, Gandhi took personal responsibility for it and threw all that he had, including his life, into his fight against violence. As a leader, he also felt that he had a duty not to step too far ahead of his colleagues, let alone go against their well-considered judgement. This was one of the reasons why he did not embark on a half-promised 'fast unto death' against the partition of the country which almost all his senior colleagues had accepted. Gandhi had his fair share of limitations. As Nehru told Lord Attenborough, Gandhi was much too human to be a saint. His views on brahmacharya strain belief, and his view of sexuality as an animal passion fails to appreciate its rich moral and emotional potential. His belief in the absolute efficacy of ahimsa was naive. As Martin Buber and others pointed out, a Gandhi would have been disposed of by the Nazis long before he had taken the first step toward Satyagraha. He had a limited understanding of the nature and depth of evil and felt bewildered in its presence. Despite these and other personal and philosophical limitations, Gandhi's ideas have the capa-city to guide us. His life, which he said was his message, had a rare depth and grandeur. On his 150th birth anniversary, we should gratefully study his thought and draw inspiration from the insights we find relevant and convincing. Courtesy: India Today, dt. 07.10.2019 * Bhikhu Parekh is emeritus professor of political philosophy at the University of Hull, UK, and a member of the House of Lords. |