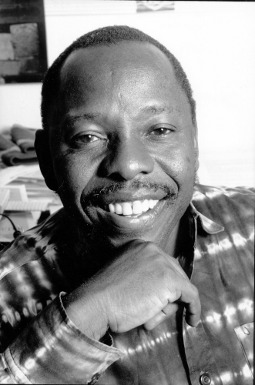

Ken Saro-Wiwa - The Nigerian Gandhi |

- By Dr Ram Ponnu

Ken Saro-Wiwa, a Nigerian patriot, an Ogoni nationalist, the father of the African environmental movement, writer, poet, essayist, playwright and TV producer, led a nonviolent campaign against the environmental degradation in the Niger Delta due to crude-oil extraction at the end of 20th century. He was the President of the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP), an organization set up to defend the environmental and human rights of the Ogoni people of the Niger Delta in Nigeria. He is popularly hailed as the Nigerian Gandhi, for he led a nonviolent campaign against the environmental degradation of the land and waters of Ogoniland by the operations of the multi-national petroleum industry, especially the Royal Dutch Shell Company. He vehemently criticized the destructive impact of the oil industry-the primary source of Nigeria’s national revenue-on the Niger delta region and demanded a greater compensatory share of oil profits for the Ogoni. He organized peaceful protests against Shell and advocated for the clean-up of the area's environment. As a result of mounting protests, Shell suspended operations in Ogoni lands in 1993. The author of children’s books, novels, plays, poetry and articles/books on political and environmental issues, Ken Saro-Wiwa produced and directed Basi and Company, a ground-breaking sitcom from 1985 to 1995 on Nigerian television, later syndicated across Africa. Early LifeKenule Saro-Wiwa was born in Bori, near Port-Harcourt, Nigeria, as the eldest son of Chief Jim Wiwa, a forest ranger who held a title in the Nigerian chieftaincy system, and his third wife, Widu, on 10 October 1941. His father's hometown was Bane, Ogoniland, whose residents speak the Khana dialect of the Ogoni language. Saro-Wiwa spent his childhood in an Anglican home and eventually proved himself an excellent student. He received primary education at a Native Authority school in Bori and then attended secondary school at Government College Umuahia. After completing secondary education, he obtained a scholarship to study English at the University of Ibadan, the first University in Nigeria. At Ibadan, he plunged into academic and cultural interests; he won departmental prizes in 1963 and 1965 and worked for a drama troupe. He briefly became a teaching assistant at the University of Lagos and later at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Saro-Wiwa was an African literature lecturer in Nsukka. When the Civil War broke out, he supported the Federal Government and had to leave the region for his hometown of Bori.1 During the Nigerian Civil War, he positioned himself as an Ogoni leader dedicated to the Federal cause. He followed his job as an administrator with an appointment as a commissioner in the old Rivers State. On his journey to Port-Harcourt, the capital city in Rivers State, he witnessed the multitudes of refugees returning to the East, a scene he described as a "sorry sight to see".2 Three days after his arrival, nearby Bonny fell to federal troops. He and his family then stayed in Bonny. He travelled back to Lagos and took a position at the University of Lagos, which did not last long, for he was called back to Bonny. In 1966, he was married to Maria Saro Wiwa. In the early 1970s, Saro-Wiwa served as the Regional Commissioner for Education in the Rivers State Cabinet but was dismissed in 1973 because he supported Ogoni's autonomy. In the late 1970s, he established many successful retail and real estate business ventures. During the 1980s, he concentrated primarily on his writing, journalism and television production. His best-known novel, Sozaboy, A Novel in Rotten English, tells the story of a naive village boy recruited to the army during the Nigerian Civil War of 1967 to 1970 and intimates the political corruption and patronage in Nigeria's military regime. Saro-Wiwa's war diaries, On a Darkling Plain, document his experience during the war. He was also a successful businessman and television producer. His satirical television series, Basi & Company, which ran for 150 episodes in the 1980s, was wildly popular, with an estimated audience of 30 million.3 In 1977, he became involved in politics, running as the candidate to represent Ogoni in the Constituent Assembly. Saro-Wiwa lost the election by a narrow margin. During this time, he had a fall-out with his friend Edwards Kobani. In 1987, he re-entered politics, appointed by the newly installed dictator Ibrahim Babangida to aid the nation's transition to democracy. But Saro-Wiwa soon resigned because he felt Babangida's plans to return to democracy were disingenuous. Saro-Wiwa's sentiments were correct, as Babangida failed to relinquish power in the coming years. In 1993, Babangida annulled Nigeria's general elections that would have transferred power to a civilian government, sparking mass civil unrest and eventually forcing him to step down at least officially that same year.4 Royal Dutch ShellAfter the Berlin Treaty of 1885, signed by the representatives of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, the United States of America, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Sweden-Norway, and Turkey (Ottoman Empire) Nigeria came under British colonial rule, but it was not until 1901 that British forces arrived in Ogoniland. The cultural differences led to resistance on the side of the Ogoni people, but as they were not strong enough to resist the British patrols, the Ogoni people were finally subjugated in 1914. The British saw Nigeria as three major ethnic groups: the Hausa-Fulani, the Yoruba and the Igbo, ignoring more than 250 smaller peoples, including the Ogoni.5 The Ogoni were regarded with contempt by all other Delta region groups and often positioned at the bottom of the social ladder. Since Royal Dutch Shell struck oil in 1958 and extracted an estimated $30 billion worth, in return, the Ogoni, a group of 550,000 farmers and fishermen inhabiting this coastal Nigeria, had received little except a ravaged environment. Fertile farmland was turned into contaminated fields from oil spills and acid rain. Uncontrolled oil spills dotted the landscape with puddles of ooze the size of football fields. Virtually all fish and wildlife have vanished. Meanwhile, out of Shell's Nigerian workforce of 5,000, less than 100 jobs went to Ogoni.6 Nigeria is infamous for oil companies’ ‘flaring’ most of the gas released during oil extraction – equivalent to 40 per cent of Africa’s annual gas consumption. Often close to villages, gas flares release poisonous chemicals such as nitrogen dioxide, benzene, toluene, xylene and dioxins. Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP)In 1990, Ken Saro-Wiwa formed the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP). This movement used non-violent means to assert the rights and recognition of the Ogoni people and their culture. Three years later, a peaceful protest mobilized 3,00,000 Ogonis. MOSOP declared that Shell was no longer welcome to operate in Ogoniland. The demonstrations by MOSOP were effective. Shell repeatedly raised concerns about Ken Saro-Wiwa and MOSOP with Nigeria’s government, framing them as a potential problem for the company that would bring negative economic impacts. In describing the effects of the environmental damages upon his people, the President of MOSOP, Dr. Garrick Barile Leton, stated in 1991: “Lands, streams and creeks are totally and continually polluted; the atmosphere is forever charged with hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide; many villages experience the infernal quaking of the wrath of gas flares that have been burning 24 hours a day for 33 years; acid rain, oil spillages and blowouts are common. Such unchecked environmental pollution and degradation result in the Ogoni no longer farming successfully. Once the food basket of the eastern Niger Delta, the Ogoni now buy food (when they can afford it); fish, once a common source of protein, is now rare. Owing to the constant and continual pollution of our streams and creeks, fish can only be caught in more profound and offshore waters for which the Ogoni are not equipped; all wildlife is dead; the ecology is changing fast. The mangrove tree, the aerial roots of which generally provide a natural and welcome habitat for many a seafood - crabs, periwinkles, mudskippers, cockles, mussels, shrimps and all - is now being gradually replaced by unknown and otherwise useless plants. The health hazards generated by an atmosphere charged with hydrocarbon vapour, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide are innumerable”.7 Ken Saro-Wiwa called it an 'ecological war' and said: “The Ogoni country has been completely destroyed... Oil blowouts, spillages, oil slicks, and general pollution accompany the search for oil... Oil companies have flared gas in Nigeria for the past thirty-three years, causing acid rain... What used to be the delta's bread basket has now become infertile. All one sees and feels around is death. Environmental degradation has been a lethal weapon in the war against the indigenous Ogoni people”.8 Ogoni Bill of RightsIn August 1990, the Chiefs and people of Ogoni in Nigeria met to sign the Ogoni Bill of Rights, one of the most important declarations to come out of Africa in recent times. By the Bill, the Ogoni people, while underlining their loyalty to the Nigerian nation, laid claim as a people to their independence, which British colonialism had first violated and then handed over to some other Nigerian ethnic groups in October 1960. The Bill of Rights presented to the Government and people of Nigeria called for political control of Ogoni affairs by Ogoni people, control and use of Ogoni economic resources for Ogoni development, adequate and direct representation as of right for Ogoni people in all Nigerian national institutions and the right to protect the Ogoni environment and ecology from further degradation. These rights, which should have reverted to the Ogoni after the termination of British rule, have been usurped in the past thirty years by the majority ethnic groups of Nigeria. They have been usurped, misused, and abused, turning Nigeria into a hell on earth for the Ogoni and similar ethnic minorities. Thirty years of Nigerian independence has done no more than outline the wretched quality of the leadership of the Nigerian majority ethnic groups and their cruelty as they have plunged the nation into ethnic strife, carnage, war, dictatorship, deterioration and the most incredible waste of national resources ever witnessed in world history, turning generations of Nigerians, born and unborn into perpetual debtors.9 The Ogoni Bill of Rights rejected once and for all this incompetent indigenous colonialism and called for a new order in Nigeria, an order in which each ethnic group would have complete responsibility for its affairs. Competition between the various peoples of Nigeria will be fair, thus ushering in a new era of peaceful co-existence, cooperation and national progress. It requested the international community to

The Ogoni Bill of Rights called for “political control of Ogoni affairs by Ogoni people, control and use of Ogoni economic resources for Ogoni development, adequate and direct representation as of right for Ogoni people in all Nigerian national institutions and the right to protect the Ogoni environment and ecology from further degradation”. The Ogoni people submitted the Ogoni Bill of Rights to the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, General Ibrahim Babangida and Armed Forces Ruling Council members on October 2, 1990. After a one-year wait, the President has been unable to grant the audience the people sought to have with him to discuss the legitimate demands of the Ogoni Bill of Rights. Their demands, as outlined in the Ogoni Bill of Rights, were fair, just and their inalienable right and in accord with civilized values worldwide. Since October 2, 1990, the Government continued to decree measures and implement policies that further marginalize the Ogoni people, denying political autonomy, their rights to natural resources, the development of languages and culture, and adequate representation of rights in all Nigerian national institutions and to the protection of their environment and ecology from further degradation.11 They were dehumanized, slowly exterminated, and driven to extinction even as their rich resources were siphoned off to the exclusive comfort and improvement of other Nigerian communities and the shareholders of multi-national oil companies. The Ogoni people authorized the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP) to represent for as long as these injustices continue, to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, the Commonwealth Secretariat, the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights, the European Community and all other international bodies which had a role to play in the preservation of their nationality. The Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria has, in utter disregard and contempt for human rights, since independence in 1960, denied political rights to self-determination, economic rights to resources, cultural rights to the development of languages and culture, and social rights to education, health and adequate housing and representation as of right in national institutions. The Federal Republic of Nigeria refused to pay us oil royalties and mining rents amounting to an estimated 20 billion US dollars for petroleum mined from our soil for over thirty-three years. It failed to protect rights as an ethnic minority of 500,000 in a nation of about 100 million people.12 The voting power and military might of the majority ethnic groups have been used remorselessly against them at every point. The multi-national oil companies, namely Shell (Dutch/British) and Chevron (American), severely and jointly devastated the environment and ecology. They flared gas in villages for 33 years, caused oil spillages, blowouts, etc., dehumanised people, and denied employment and those benefits that industrial organizations in Europe and America routinely contribute to their areas of operation. The people did not seek restitution in the courts of law when the act of appropriation of rights and resources had been institutionalised in the Constitutions of 1979 and 1989, imposed by the military regime, which did not protect minority rights or bear a resemblance to the tacit agreement made at Nigerian independence. MOSOP stands for the Ogoni people's right to choose the use of their land and its resources. They have survived being marginalized and occupied by the state into the new era of Nigeria's fragile and imperfect democracy. MOSOP remained a leading advocate for dialogue, justice and democratic, non-violent change. MOSOP strives for a future where all “stakeholders” in Ogoni's human and natural wealth can experience peace and prosperity as equal partners.13 In November 1990, Ken Saro-Wiwa wrote an article, "The coming war in the Niger Delta", to Nigeria's Sunday Times editor. It was not published. The report highlighted his campaign for environmental protection and a fair share of oil revenue for his Ogoni people and other ethnic groups of the Niger Delta. Saro-Wiwa was told that the military government had taken exception to his warning that the delta would erupt in violence if western oil companies and the state failed to meet local people's reasonable demands. Saro-Wiwa saw that authoritarian rule and domination of smaller ethnic groups by the larger ones would force the Delta people into an impossible position. He urged an immediate remedy but embraced the nonviolent tradition of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. He urged the angry young men of Mend to put down their guns and engage with the government peacefully. Yet all he received from the government and oil companies was slander, harassment and, ultimately, the most severe form of censorship: death.14 As Nigerians prepare for make-or-break elections, as oil prices continue to surge, and as the spectre of global warming hovers over us all, governments and citizens across the world should ponder the words uttered by Saro-Wiwa in his final hours: "We all stand on trial, my lord, for by our actions we have denigrated our country and jeopardized the future of our children; as we subscribe to the sub-normal and accept double standards, as we lie and cheat openly, as we protect injustice and oppression, we empty our classrooms, denigrate our hospitals, fill our stomachs with hunger and elect to make ourselves the slaves of those who ascribe to higher standards, pursue the truth, and honour justice, freedom, and hard work. I predict that scene here would be played and replayed by generations unborn. I call upon the Ogoni people, the peoples of the Niger Delta, and the oppressed ethnic minorities of Nigeria to stand up now and fight fearlessly and peacefully for their rights. History is on their side. God is on their side.”15 The hallmark of Saro-Wiwa's civil rights campaigns was non-violent and peaceful action, for which he referred to Gandhi for inspiration. He produced a film featuring scenes of gas, flaring, burning incessantly in proximity to shacks and 'primitive schools whose metal roofs have been corroded with acid rain. The film also portrayed high-pressure oil pipelines cris-crossing Ogoni farmlands and villages. Through Saro-Wiwa's non-violent approach, the attention of the United Nations was attracted to the condition in the Niger Delta, and Ogorii land in particular.16 ExecutionIn 1992, the Nigerian military government imprisoned Saro-Wiwa for several months without trial. Saro-Wiwa was Vice Chair of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) General Assembly from 1993 to 1995. UNPO is an international, nonviolent, and democratic organization (of which MOSOP is a member). Its members are indigenous peoples, minorities, and unrecognized or occupied territories. They have joined together to protect and promote their human and cultural rights, preserve their environments, and find nonviolent solutions to conflicts that affect them. On January 4, 1993, around 300,000 Ogoni people in Rivers State peacefully protested against the environmental devastation of their land caused by the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria (SPDC) subsidiary of Royal Dutch/Shell. They led a march peacefully to demand a share in oil revenues and political autonomy. MOSOP also asked the oil companies to begin environmental remediation and pay compensation for past damage. Saro-Wiwa was arrested several times in 1993 when Amnesty International adopted him as a Prisoner of Conscience and became MOSOP President. The Nigerian government arrested Saro-Wiwa at a political rally in May 1994, allegedly for being responsible for the death of four Ogoni tribal leaders. The trial was widely judged flawed and unfair, and the charges were politically motivated. ‘I and my colleagues are not the only ones on trial. Shell is here on trial… The company has, indeed, ducked this particular trial, but its day will surely come, and the lessons learnt here may prove useful to it, for there is no doubt in my mind that the ecological war that the company has waged in the [Niger] Delta will be called to question sooner than later and the crimes of that war be duly punished.’17 Evidence suggests that Shell bribed witnesses, and Shell had also been meeting secretly with the Nigerian military government. In a trial by a special tribunal that foreign human rights groups denounced, he was found guilty of alleged complicity in the murders. The Abacha regime set up the Auta Tribunal after falsely accusing Saro-Wiwa of orchestrating the death of four Ogoni elders. After prolonged abuse, torture and intimidation of Wiwa's counsel by the Abacha regime, Justice Auta pronounced Saro-Wiwa and eight Ogoni activists guilty of a crime they never committed and sentenced them to death by hanging.18 In his statement at the tribunal: “I am a man of peace, of ideas, appalled by the denigrating poverty of my people who live on a richly endowed land, distressed by the political marginalisation and economic strangulation, angered by the devastation of their land, their ultimate heritage, anxious to preserve their right to life and to a decent living, and determined to usher to this country as a whole a fair and just democratic system which protects everyone and every ethnic group and gives us all a valid claim to human civilisation, I have devoted my intellectual and material resources, my very life, to a cause in which I have total belief and from which I cannot be blackmailed or intimidated... In my innocence of the false charges I face here, in my utter conviction, I call upon the Ogoni people, the peoples of the Niger Delta, and the oppressed ethnic minorities of Nigeria to stand up now and fight fearlessly and peacefully for their rights”.19 After the trial, which international observers condemned and described as judicial murder by the then British Prime Minister. Nelson Mandela, global human rights icon and first Black President of South Africa, pleaded with Sani Abacha, former Nigerian military Head of State, to pardon Ken Saro-Wiwa. In July 1995, he led a small delegation of his Government to Nigeria to meet General Abacha, persuading him to release the political prisoners, including Ken Saro Wiwa and eight of his colleagues.20 But he was murdered during the ruthless military administration of General Sani Abacha in a prison yard in southern Nigeria on November 10, 1995, in defiance of international appeals for leniency by the military government of General Sani Abacha, on charges widely viewed as entirely politically motivated and completely unfounded. His execution by hanging, along with those of eight fellow activists, aroused international condemnation and led to calls for economic sanctions against Nigeria, which was suspended from the Commonwealth a day after the executions. His death and his character became a symbol of environmental protection and human rights. His death triggered international outrage. Shell later announced its commitment to a natural gas project worth nearly $4 billion, one of the most significant foreign investments in Nigerian history. In a 2009 settlement, Shell paid $15.5 million to one group of activists' families, including the Saro-Wiwa estate, in the United States. But again, the oil and gas conglomerate denied responsibility. This is one of a series of environmental lawsuits brought against the global energy firm. In 2011, the United Nations published a report putting the cost of cleaning the area at $1 billion (931 million euros). Removing all the damage will take 30 years. Igo Weli, the spokesperson for Shell Nigeria, explained the company's stance on the clean-up. "We are working with the government to implement measures as soon as possible. We want to help – and be part of the solution," he added. That is something many Ogoni doubt very much. The human rights agency Amnesty International accuses oil groups of not thoroughly cleaning up the environment.21 After a 13-year legal battle, in 2021, the same Dutch court ordered Shell to compensate Nigerian farmers for spills that contaminated swathes of farmland and fishing waters in the Niger Delta. The company agreed to pay more than a hundred million dollars.22 RecognitionSaro-Wiwa’s most important legacy was the push to hold corporations accountable when their operations violate local or international laws and the companies hide behind a complicit or ineffectual government.23 In 1994, MOSOP, along with founder Ken Saro-Wiwa, received the Right Livelihood Award for their exemplary courage in striving non-violently for the civil, economic and environmental rights of their people. Saro-Wiwa was nominated in 1995 but never came close to winning the Nobel prize during his lifetime. However, he won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, an annual international award for environmental activists, and the Swedish Right Livelihood Award, often called the "alternative Nobel Prize." A memorial to his actions was unveiled in London in 2006. The Association of Nigerian Authors sponsors the Ken Saro-Wiwa Prize for Prose, and he is named a Writer Hero by the My Hero Project. Amsterdam has a street named after him. To conclude, Saro-Wiwa was a world-renowned peace advocate who fought for the liberation of the Niger Delta but was cut down in his prime by the Gen. Sani Abacha military junta. The only crime Ken Saro-Wiwa and his colleagues had committed was to demand sound environmental practices and to ask for compensation for the devastation of Ogoni territories. Ken Saro-Wiwa paid for his courage with his life, but his selflessness continues to inspire. He said: "The inconveniences which I and the Ogoni suffer, the harassment, arrests, detention, even death itself are a proper price to pay for ending the nightmare of millions of people." Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life has provided a legacy of great inspiration for human rights and environmental activists worldwide. End Notes

* Formerly Principal, Kamarajar Govt. Arts College, Surandai, Tamil Nadu, India. Email: eraponnu@gmail.com |