Mahatma Gandhi: A Life in the service of Humanity |

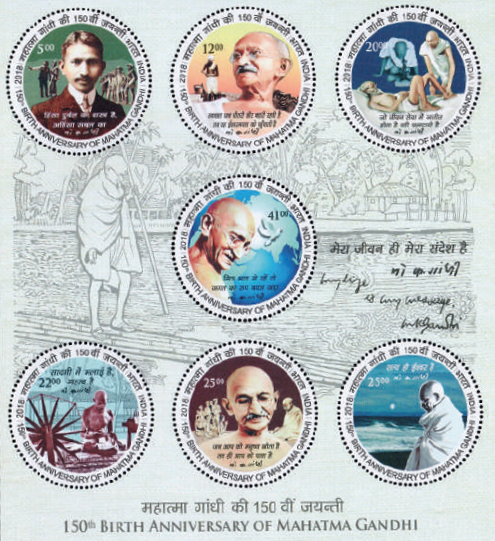

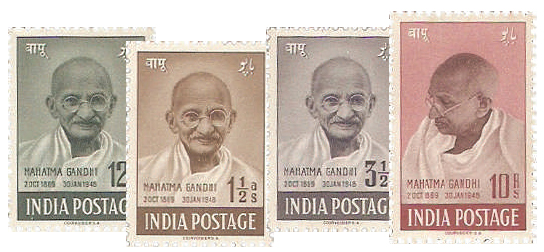

Pradip Jain FRPSL* This October will mark the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian lawyer turned social activist who championed the cause of liberty and freedom through the means of non-violence. Pradip Jain looks back on the life of a man who, through the practice of satyagraha or non-violent resistance, would lead India into independence and be named Bapu - the Father of the Nation. The year 2019 marks the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi (1869−1948), the civil rights activist who led India into independence and set an example for others to walk on the path of non-violence and passive resistance to reach their ends. Postal administrations from all over the world are honouring this great personality, revered in India as Bapu - the Father of the nation, by issuing commemorative postage stamps to celebrate the anniversary. A man of enormous courage, principle, faith and determination, Mahatma Gandhi became one of the most important and recognisable figure of the 20th century, thanks to his peaceful yet powerful philosophy of ahimsa (non-violence). Today, when violence is spreading in the name of religion, caste and community, Gandhi's ideology of non-violence has probably never been more relevant. The importance of Gandhi's ideology of non-violence has been celebrated by numerous institutions, not least the United Nation, which represents more than 200 countries of the world. In 2007, the UN declared 2 October, Gandhi's birthday, to be observed as International Day of Non-violence. The UN issued its first commemorative cachet for the day in 2007 and its first stamp in 2009 - featuring non-other than Gandhi himself. Since then many other countries have joined hands to honour this day. Early LifeMohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in the small coastal town of Porbandar in the erstwhile state of Gujrat, India. His father, Karamchand, was deewan (prime minister) of Porbandar and his mother, Putlibai, was a religious woman who was well informed with matters of state. At the age of seven, the family moved to Rajkot where Mohandas completed his primary and high school education. As was then normal in Indian society, in 1882, at the age of 13, Mohandas entered into an arranged marriage with Kasturba, who was of the same age. For both of them, marriage was nothing more than wearing new clothes, a round of feasts and a strange new companion. This long-lasting relationship only ended with the death of Kasturba in 1944. Gandhi was deeply influenced with the doctrines of Jainism, in particular the teachings of Lord Mahavir (599−527 BC), the last spiritual teacher of the Jain religion. Gandhi was to follow these beliefs throughout his life. Shrimad Rajchandra, a jain scholar, became both Gandhi's mentor and refuge in times of crisis. Gandhi the barristerAfter completing high school, Gandhi moved to England to study law. During his time in London, he adhered to western culture of lifestyle, such as English food and clothing, and other mannerisms. After his graduation, he returned to India and started a practice in Bombay, but this was not very successful. In 1893, he sailed to South Africa in response to an offer from an Indian firm, Dada Abdullah & Co., to work as their legal advisor. This was to be the turning point in Gandhi's life and the start of his transformation from Mohandas to Mahatma (Great Soul). Although only contracted to work for one year in South Africa, Gandhi would spend the next 21 years in the country, fighting for the civil rights of Africans and Asians. Life in South AfricaGandhi had a difficult start to his life in South Africa. Within two days of arriving he was chastised in a Durban court for his refusal to remove his turban and was ordered to leave the building. When he complained about his treatment to the local press, a newspaper story referred to him as 'an unwelcome visitor'. Just a week later, in June 1893, while on his way to Pretoria from Johannesburg for a court case, Gandhi was forcibly removed from a first-class coach for being a coloured passenger. After objecting, he was thrown off the train at Pietermaritzburg, Natal, where he spent the night in a cold waiting room. This incident was to change the course of Gandhi's life. From that moment, he vowed to fight against racial oppression. The fight beginsIn April 1894, after concluding his work for Dada Abdullah, Gandhi planned to return to India. However, during his farewell party he read about a new law that would deprive Asians of representation in the legislature. The party quickly turned into a working committee and Gandhi decided to extend his stay in South Africa in order to fight against this law alongside other local Indians. In a petition drive led by Gandhi, over 10,000 signatures were collected in a fortnight. Gandhi took his grievances to Lord Ripon, secretary of state for the colonies, who had the bill temporarily set aside. Unfortunately, this was only a short deferment and the law was later passed. Determined to keep up the fight, in September 1894 Gandhi applied for permission to practice law in the Natal Supreme Court. The Natal Law Society objected his application based on his race and colour, but his application was later accepted by the chief justice. Later that year, Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress to carry on the work against discriminatory legislation. In this period, Gandhi worked hard on behalf of Indian settlers, many of whom were illiterate and knew little about the few rights they had. He battled for labour rights and immigration issues for indentured workers across South Africa, organising walkouts and strikes in mines. By now, Gandhi had become a renowned Indian figure in South Africa. Military serviceDuring the Second Boer War (1899−1902), Gandhi organised and led the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. He served in Estcourt from 19 December 1899 until the Indian Ambulance Corps was disbanded on 28 January 1900, following the arrival of the British Red Cross. For his service Gandhi was awarded the Queen's South Africa campaign medal. Later in 1900, Gandhi temporarily returned to India to take care of his family. While there, in 1901 he attended the session of the Indian National Congress to highlight the plight of Indian people in South Africa. He returned to Natal in 1903 where he established the weekly newspaper, the Indian Opinion. The publication was an important tool for the political movement led by Gandhi and the Natal Indian Congress to fight racial discrimination and win civil rights for the Indian immigrant community in South Africa. In 1904 Gandhi founded the Phoenix communal settlement near Durban and the publishing office was relocated there. Insistence of truthIn 1907, Gandhi led a passive resistance movement against the compulsory registration of Indians in Transvaal. This was the beginning of satyagraha (insistence of truth), which took the form of peaceful protest through civil resistance. Gandhi travelled over large parts of Africa, gathering Asians for satyagraha. Those who took part in the protests were prepared to go to prison rather than to submit to unjust laws. Gandhi himself was imprisoned several times for his part in the protests. Gandhi's main antagonist in South Africa was General Smuts, Transvaal's colonial secretary. Gandhi was imprisoned three times by Smuts, but did not abandon his principles. The continued protests forced Smuts to set up a commission to investigate Indian grievances. This would ultimately lead to the passing of the Indian Relief Act and in 1914 Gandhi suspended his passive resistance movement. This major victory paved the way for Gandhi to return to India. Whilst a prisoner in a Johannesburg jail, Gandhi had made a pair of sandals with his own hands. He gifted those sandals to Smuts before sailing to India. Smuts admitted on an occasion - 'I have worn these sandals for many a summer, even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man'. Return to IndiaGandhi finally returned to India in 1915. Initially he stayed at Kochrab Ashram, which belonged to Jivanlal Desai, a fellow barrister and friend. Initially, he refrained from politics, taking a vow of silence while taking time to understand the present India. By now, Gandhi started living a life as an ascetic. He spent his time taking daily prayer and reading books. He was deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau's Civil Disobedience, an argument for disobedience to an unjust estate. He also exchanged letters with the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy and was greatly influenced by his book The Kingdom of God is Within You and his essay Christianity and Patriotism. Tolstoy's ideal of 'simplicity of life and purity of purpose' reflected Gandhi's own personal philosophies. Gandhi eventually joined the Indian National Congress and in 1916, during the foundation stone laying ceremony of the Benares Hindu University, he gave his first public address in India. During his speech to the gathered students and dignitaries, which included the British Viceroy, he expressed his grief as being compelled to address the crowd in a foreign language. The Champaran SatyagrahaIn the 1916 session of Congress, Gandhi met with Raj Kumar Shukla, a representative of farmers from Champaran in Bihar. Shukla asked Gandhi to visit the region to see the plight of the indigo planters there. On arrival, Gandhi witnessed the misery of the local indigo planters who were forced to cultivate the poisonous crop with little or no payment - effectively being forced into suicide. He immediately began to gather people to fight against the horrid conditions he witnessed. However, in an attempt to put an end to his interference, Gandhi was served with a notice from the British district magistrate ordering him to leave the town by the first available train. Gandhi refused and was arrested. However, he was released and the case was withdrawn two days later. This was the first small victory, but much more had to be done. Realising that a lack of education was one of the main reasons why the landowners were able to repress the farmers, Gandhi decided to stay in Champaran and, along with his wife, set up the region's first free schools. Using the same practice of satyagraha, which had been successful in South Africa, Gandhi organised protests and strikes against the landlords, who, with the guidance of the British government, signed an agreement granting more compensation and control for the farmers. The Champaran satyagraha was the first civil disobedience movement launched by Mahatma Gandhi in India and is considered to be a vital event in the history of India's freedom struggle. Gandhi's victory in Champaran made him popular all across India. By 1920 Gandhi's faith in the British colonial government was diminishing and he was swept to the forefront of Indian politics. He became president of the Indian National Congress and transformed it into a powerful political tool in the struggle for independence. His vision of an India free from British imperial rule caught the imagination of the people. Gandhi and the spinning wheelGandhi strictly opposed any form of violence against the British, even when severely opposed. He regularly wrote articles and messages about social change in his famous newspapers Young India, which he started in 1919, and the Harijan, which he first published in 1933. In his articles, Mahatma Gandhi often used the charkha (spinning wheel) as a symbol of non-violence and self-reliance: 'I would make the spinning wheel the foundation on which to build a sound village life. I would make the wheel the centre round which all other activities will revolve,' he said. The charkha was to become synonymous with Gandhi and a symbol of India's independence movement. The Great SoulBy now Gandhi had been transformed into Mahatma (Great Soul), a title conferred upon him by Indian noble laureate Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore later wrote of the occasion, 'At Gandhi's call, India blossomed forth to new greatness and he will always be remembered as one who made his life a lesson for all ages to come'. Gandhi and the untouchablesGandhi fought for the rights of all people and had great sympathy with the untouchables - people considered to be at the bottom of the discriminatory caste system that was prevalent at the time. Gandhi would often stay in the untouchables colony in Delhi, looking after their welfare and education. According to Gandhi, 'Untouchability and division of society on the basis of caste and creed is tantamount to moral violence'. Boycott British GoodsIn 1921, Gandhi, now on the forefront of the Indian Independence movement, launched a campaign calling for the boycott of all British goods. The campaign aimed to curb the economic control and exploitation of Indian masses and artisans at the hands of the British. Various patriotic labels and hand-stamps reading, 'Boycott British Goods' or 'Boycott Foreign Goods' were produced to publicise the civil disobedience movement. The protests quickly extended beyond a simple boycott and British goods were set on fire by the masses in support of the campaign. This caused panic amongst the officials in the British Government due to huge economic losses, which led to the issue of an ordinance that prohibited the use of the labels on mails and the spreading of propaganda. As a result of the ban, the labels are rarely found on Indian mail. In 1930 Gandhi embarked on his historic Salt March - a 240-mile march from Sabarmati to the town of Dandi in protest of the salt tax imposed on Indian people. Thousands of people joined the satyagraha and mass civil disobedience spread throughout India as millions broke the salt laws by making salt or buying illegal salt. The march was one of the most significant events in the annals of the civil disobedient movement. In reaction, the British government arrested over 60,000 people, including Gandhi, who was sent to Yerwada prison in Poona. Negotiation for freedomAfter the Salt March, the British government started to negotiate with the Indian National Congress. Gandhi was released from prison and invited to attend the second Round Table Conferences held in London in 1931. However, the two sides failed to reach an agreement on independence. In 1942, at the height of World War II, Gandhi and the Indian Congress launched the, with its slogan 'Do or Die'. This was a mass civil disobedience movement designed to force the British to grant independence. At the end of the war, the British Government, realising that India was now ungovernable, finally accepted its independence. India became free at the stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947 and Britain prepared to leave India. Gandhi succeeded in laying the foundation of modern independent India through his ideology and preaching of non-violence, equality and liberty for all which became the bedrock of the Indian Constitution and guiding light for the largest democracy of the world. From this moment, Gandhi became known as Bapu - the Father of the Nation. However, the resulting partition of India and the formation of Pakistan divided the 5000-year-old civilisation on a scale never thought possible by Gandhi, who always advocated for secularism and harmony. Communal violence spread between Hindus and Muslims, Sikhs and Muslims. In an attempt to stop the violence, Gandhi began to fast, which weakened him almost to the point of death. The postal department issued a slogan cancellation asking people for 'Communal Harmony' in order to save Gandhi. AssassinationOn 30 January 1948, as he was making his way to evening prayer, Gandhi was assassinated. His last words were 'Hey, Ram' (Oh, God). To commemorate the first death anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, on 30 January 1949 all postal items sent in India were impressed with a postmark bearing the slogan 'May God Grant sense to everyone'. Gandhi on stamps The first stamps to depict Gandhi was a set of four values issued by India on the first anniversary of independence in 1948. Mahatma Gandhi has been depicted on a vast number of stamps from a huge number of countries. India was the first country to pay tribute to him with a stamp issue. In 1948, on the first anniversary of independence, it issued a set of four stamps using the word 'BAPU' in Urdu script. In 1961, the US was the first foreign country to issue a commemorative stamp for Mahatma, honoured him with the title 'Champion of Liberty'. Later, Mahatma Gandhi became the first foreign personality to be featured on a British commemorative stamp. This was a 1s.6d. value issued in in 1969 marking his birth centenary and honoured Gandhi's dedication to bringing about India's independence through non-violence. The honour of designing this stamp was bestowed upon an Indian designer, Biman Mallick. Following in his footstepsMahatma Gandhi set an example of non-violent protest as a means to achieve freedom from oppression and unjust rule. Walking on his footsteps were Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, etc. who worked tirelessly for civil liberty, equality and rights of the deprived. A collective effort by these individuals have set a benchmark for others to follow. For his lifelong work, Mahatma Gandhi was adjudged to be India's Man of the Millennium in 2001. In true sense, 'His life was his Message'. Courtesy: Gibbons Stamp Monthly, October 2019 * Pradip Jain is a well-known Gandhi collector, internationally known for Gandhi collectible and author of 'Mahatma Gandhi on stamp' hand book. | Email: philapradip@gmail.com |