The Satyagrahi in South Africa |

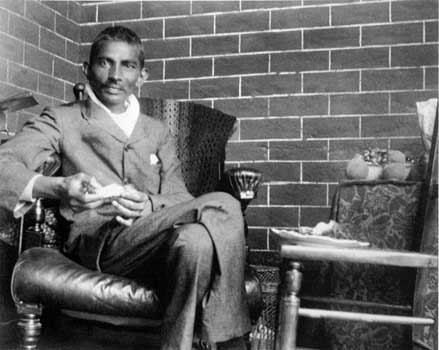

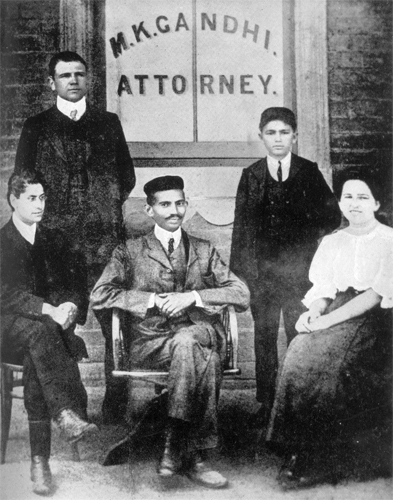

- Nechama Brodle The Man who became the Mahatma In January1908, Gandhi, along with thousands of Hindus and Muslims, gathered to burn the registration papers that the government required all "Asiatics" to possess. Gandhi was arrested, but released from prison when General Jan Smuts promised to repeal the laws if all Asiatics first complied with voluntary registration. In February, Gandhi was assaulted by a former client who felt he had betrayed the cause. In this photograph. Gandhi is convalescing at the house of his close associate Reverend JJ Doke after the attack. Hundred years is a long time, particularly in a town only a little older than a century itself. The road to Tolstoy Farm, Mahatma Gandhi's penultimate residence in South Africa, is no longer marked, if indeed it ever was. To get there I have to head south along Lenasia Drive and then follow a set of rather cryptic directions provided by an urban geographer and a sociologist. The farm was founded in 1910, the same year Count Leo Tolstoy would die. Gandhi was a great fan of the Russian writer and the two had exchanged several rather beautiful letters, rich with ideas and encouragement. During Gandhi's time, Tolstoy Farm was home to a thousand fruit trees, and up to 50 adults with half as many children. An arrangement of corrugated iron sheds served as living quarters, a school and a workshop. Tolstoy Farm was a communal settlement, providing a place of retreat for Gandhi, and offering sanctuary to the satyagrahis and their families. The land had been given by Gandhi's dearest friend, the architect Hermann Kallenbach, who ran a carpentry school on the premises. Some years after Gandhi's final departure from South Africa in 1914, Kallenbach built a permanent structure on the farm, the remains of which are all that can be seen today. Like the building, the fruit trees are long gone. The only regular visitors are the cows that come to graze on the surrounding grass. Although Gandhi spent nearly 20 years of his life in South Africa - much of this time in Johannesburg - reconstructing the landscape of his time there, is no easy task; many structures have been demolished; others, like the farm, have been abandoned and neglected. Even those that do remain, seem, for the most part, to be largely forgotten. It is possible, of course, to retrace what writer Lucille Davie has described as Gandhi's "gentle footstep", but it is a pilgrimage that requires equal parts of commitment, curiosity and imagination. Gandhi would have first encountered Johannesburg by train in June of 1893 - the same journey that would transform his life's path. While en route from Durban, to represent his employer at a case in the capital of Pretoria, Gandhi was evicted from the "whites only" first-class section and forced to spend a night at the station in Pietermaritzburg. Rather than deter Gandhi, this incident, his first encounter with such state-sanctioned racism, seemed to galvanise the young lawyer, initiating him into the "full experience of the condition of Indians in South Africa". Nine years later, after the end of the South African War and a spell in India, Gandhi settled in Johannesburg, and set up a small law office on Rissik Street near the High Court. When the courts were relocated and the buildings demolished, in the 1940s, the surrounding land was redeveloped into a bus terminus. In 1999, the area was renamed Gandhi Square. A 2.5m bronze sculpture of Gandhi, in his lawyer's gown, now stands there. In typical Joburg fashion, it is installed with a motion-sensitive alarm, to deter thieves from any attempts to hawk such a valuable piece of the city's heritage. In 1904, Gandhi moved from the small space behind his offices into a house in the eastern Johannesburg suburb of Troyeville, where he shared a house with his wife Kasturba and their family; and with Gandhi's law associate Henry Polak and his wife Millie, a pair of vegetarians (which was how Polak and Gandhi first met) and radical thinkers. Two houses on Albermarie Street - one at number 11, the other at number 19 - bear identical blue plaques marking them as national monuments. Both are known as "the Gandhi House". Only one of these claims is correct, but it's never really been proven which house has the advantage over the other. And so the buildings quietly share the honour. "It's not really that important whether he lived in this house or not, or a few houses up the road," says architect Michael Hart, who lives in at number 19 and carefully and lovingly restored the house over 20 years ago. "What's interesting for me is that he lived in this street. He would have walked past these houses, visited the people in them, seen the same views. The mythology and intrigue around Gandhi is much more valuable - it tells us about old Johannesburg, about the personalities that made a mark. For me, as an architect who is interested in heritage, what we do is document and preserve interesting facts for the next generation so those histories aren't lost." West of the city centre, in the suburb of Newtown (which Gandhi would originally have known as the racially mixed area of Brickfields, before authorities intervened and invented a case of bubonic plague, subsequently burning the entire settlement down and building a white suburb in its place - Johannesburg's first example of urban "renewal") there are two dissonant dedications to Gandhi's years in Joburg. The first is a narratively comprehensive but otherwise one-dimensional exhibition at the city's official - and sadly neglected-museum, Museum Africa (121 Bree Street). The second is tucked away on Jenning Street, opposite the entrance to the Hamidia Mosque. Here one can find a small monument in the shape of a cauldron (which bears resemblance to an outsized cooking pot or potjie), topped with a sheet of metal bearing the word "TRUTH". It is a necessary token but, perhaps, inadequate to the task at hand, for it was here, in the courtyard facing the mosque, that Gandhi led one of the most important early actions of defiance.  Here, Gandhi is seen outside his office in 1906. Seated to his right, is his secretary Sonja Schlesin and on the left, his colleague, the Jewish radical lawyer Henry Polak. In August 1908, Gandhi, together with a crowd of several thousand Hindus and Muslims, gathered to burn the registration papers that the government required all "Asiatics" to possess, and without which they would face expulsion from the Transvaal - a forerunner of the racist dompas or pass-book system the apartheid regime would later enforce. "The problem is that this contribution to the peace of the world is slowly being forgotten," says Chotubhai Makkan who, at 91 years of age, bears the unique distinction of having witnessed both the Dandi Salt March in 1930 - when he was six years old, before moving to South Africa - and the signing of the historic Freedom Charter in Johannesburg, in 1955. "Our youngsters are not interested," Chotubhai tells me. "They don't follow up on history," he says, adding that, at times, it is as if history is no longer taught or explained in schools. "Even my autobiography," he says, "I can only give it to persons aged 60 years and over, who knew the situation previously. If I give it to a youngster, he will say: who is that?" Surprisingly, it is another relatively unassuming house that may provide the most tangible real world connection with Gandhi's life in South Africa. Before the creation of Tolstoy Farm, Gandhi and Kallenbach lived together in a farm-like house (designed by Kallenbach) known as the The Kraal (a kraal is a cattle enclosure), at 15 Pine Road. Until 2009, "The Kraal" remained as a private residence. When the owners decided to relocate, the property was put up for sale. A news report sparked a bidding war - with the government of India reportedly losing out to the eventual winner, French Travel Company Voyageurs du Monde, who then restored it into what is now a museum and guesthouse. Renamed Satyagraha House, the boutique venue - somewhat ironically, described as decorated in a style of "Gandhi chic" (its rooms adhere to clean and minimalist principles) - does, nevertheless, open a rare window of imagination onto the intersection of the man and the Mahatma. "I hadn't really followed a lot of Gandhi's life," says journalist Verashni Hutchinson, who recently visited Satyagraha House, "and I wanted to go to a place that symbolised him. Gandhi has a complicated history in South Africa, and his legacy in South Africa has become more so because of his attitude towards Africans. But I was struck by how peaceful it was and heartened that a space had been created to honour him in a beautiful way I kept thinking what conversations they must have had, sitting there," she says. "I could picture Gandhi sleeping. It was so great to be able to walk where Gandhi had walkedand then, later the same day, to visit Gandhi Square and walk from there to Mandela's former law offices, to walk where Mandela had walked." Source: Reproducted from BRUNCH, Hindustan Times, Sept. 28, 2014 Nechama Brodie is a South African journalist and researcher, and spends her time collecting stories in Johannesburg and Cape Town. She is the author of The Joburg Book (Pan Macmillan). | Email: brunchletters@hindustantimes.com |