My Magical School |

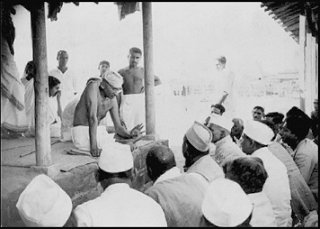

Dr. Abhay Bang

As a child I went to an amazing school. Today, I feel helpless and sad for I'm unable to offer such an education to my son - Anand. "Our childhood was so different. Things have changed beyond recognition," old timers often moan and groan about the past. Still, my heart is heavy. You may ask what was so different about my school? Until standard ninth I studied in a school which followed the tenets of Nai Taleem (Basic Education) as enunciated by Gandhiji. Out of these I actually spent four years in the Nai Taleem School located in the Sevagram Ashram in Wardha. Education should not be confined within the four walls of the classroom mugging up boring subjects away from Mother Nature. Gandhiji's Nai Taleem strongly believed that children learnt best by doing socially useful work in the lap of nature. This is how children's minds would develop and they would imbibe a variety of useful skills. To implement such a system of education, Rabindranath Tagore at the behest of Gandhiji sent two brilliant teachers to Sevagram. Mr. Aryanakam came all the way from Sri Lanka and Mrs. Asha Devi from Bengal. This duo combined Gandhi's educational methodology with Tagore's love for nature and the arts. My parents were involved with this educational experiment right from its onset. The school tried out many novel experiments in education. Here, I will attempt to recall some of them. Introduction to AnimalsToday there is a great deal of talk about conserving nature and wildlife. But 27 years back this subject was not so much in vogue. Our Marathi teacher Mr. Patil used to conduct his classes sitting on the branch of a jackfruit tree. He used to regale us with stories from the jungle. He also told us tales about his experiences as a shikari. Once by mistake he shot a pregnant she deer. Later, he simply couldn't bear to see the anguish in her eyes. This hurt him so deeply that he abandoned the gun for good. Later he only shot animals with his camera. Photographing wild animals became his passion and often he spent nights sitting alone on a machaan atop a tree to take a good shot. The stories he told us showed his deep love and compassion for animals. Listening to his stories was like going into a trance. It seemed as if we ourselves were trudging the jungle trail. Mr. Patil was a wordsmith and could paint the picture of the jungle in words. His stories made a deep impact on me and I soon started loving the jungle and its wildlife. Nowadays chapter on animals in Marathi text books usually begins with a drab sentence, 'Animals are living beings too." Will such inane words ever succeed in firing the children's imagination and inspire them? The Gadchiroli District of Maharashtra in India is still verdant green with thick jungles. But even here the school curriculum seems totally disconnected with the jungle and its wildlife. Festival of SaintsWe did not have to swallow the couplets of Saint Tukaram like a bitter pill. Every monsoon our school hosted a festival of saints. We would write essays, draw pictures, build murals and enact short plays depicting the inspiring events of the lives of saints. Not just a few, but each and every single child participated in this event. For a full fortnight there were festivities in the school. Here I learnt to recite one couplet by Saint Tukaram in three different ways. During the festival different holy songs were sung. It's in one of these musical choirs that I first learnt to sing raag "Bhairavi". We learnt many important lessons in a festive atmosphere of play. These included the sermons of saints, their history and their contributions to philosophy. There was however, one important difference. All these we learnt in a very playful manner without tags of 'language', 'music' or 'philosophy' attached to them. After many years when I visited a Government School I saw the same couplet by Saint Tukaram in a fat dreary Marathi textbook titled "Kavya Kusumanjali". Saint Tukaram himself would have felt pained seeing it. How I learnt Botany?In most schools botany is taught through textbooks with good photographs or line drawings or with live specimens stowed away in jars. Children try hard to mug-up difficult to pronounce botanical names of various species of plants and the different varieties of their leaves and roots. After the exams they soon forget all this jargon. There were a lot of gardens and fields near our school which boasted a vast variety of plant life. The best part was that our teachers regularly took us for field visits and excursions. On these outing we would closely observe plants. Our first introduction to any plant was by its common name so that we become "friends" with it. Later we observed their leaves, flowers and fruits more closely. In the end we would pluck fruits and berries and eat them. (Later in America I also ate and tasted "specimens" in class as an integral part of learning. But in America there was also a strong tradition of eating chocolates and drinking coke in the class). While eating jujube berries and mangos we would discuss similarities in these fruits. On seeing a drupe (fleshy fruit with a single hard stone inside) we would note its characteristics. Our daily wanderings in the gardens and fields brought us very close to nature and this helped us understand the fine nuances of botany. The tall theories and intricate principles of botany lay scattered in front of us in all their pristine glory. Our teachers inspired us to touch them, feel them and inspect them minutely. That's why big words like 'palmate, divergent and reticulate' never ever foxed me. The reason was simple. The Papaya leaf which these high sounding words described was right there in front of me. For the seventh class exam our teacher asked us to prepare a scientific album (herbarium) of various leaves and flowers. For this we scoured all the local gardens and neighborhood fields. Even twenty-five years later I starkly remember every single location and hideout where 'palmate, divergent and reticulate' leaves could be found. It still seems to me that those Papaya trees are standing right in front of my eyes. This had amazing consequences. During my college days I did not have to struggle at all to learn botany. In the final year, I stood first in botany in the entire college. When my professor praised me, I uttered these words silently, "Sir, I did not learn botany in college. I learnt it long back in my Sevagram School." Mathematics which is related to real life"There is a water tank with two taps. One taps fills the tank, the other drains it out. How long will it take to fill up the tank?" Our books on mathematics are replete with such senseless questions. The moot question is, "Is there any link between mathematics and real life experiences?" Any clever person will get rid of the problem by closing the lower tap! I will give an example how I learnt the concept of volume in my school. It was mandatory for us to do constructive work for three hours every day. This was an integral part of our education. This was part of Gandhiji's philosophy of "Bread Labor" where you labored to grow your own food. It was also part of Vinoba Bhave's vision of gaining various skills by doing socially productive work. For this I had to go and work in the cowshed for a couple of days. A new cowshed was then under construction. My teacher gave me the job of solving a specific practical problem. "Find the amount of water which a cow drinks in a day. How much water will be needed for all the cows in the cowshed? Then construct a water tank with the capacity to satiate the thirst of all the cows. Find out how many bricks will be required to construct such a tank? Then go and buy that number of bricks." For over a week I grappled with this mathematical problem. There were numerous tanks with varying sizes. How to measure their volume? What was the relationship between the volume and the outer surface area of a tank? I actually constructed a water tank and in the process learnt a great deal of real life mathematics. Learning through CookingHere is another example of learning good science by engaging in useful social work. In our school the students had to take turns to cook. Everyday a hundred people ate in the school mess. The responsibility of cooking was handed by turn to a group of eight people. The expenditure per head per month was announced in advance. The food had to be tasty, nutritious and the expenses had to be within the stipulated budget. Balancing these disparate acts was indeed a very tough task! Potatoes were the cheapest but they mainly contained starch and had to be discarded on nutritional grounds. By using the minimal quantity of oil stipulated by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) we would have exhausted our entire budget on oil itself! None of us had the experience of a good housewife. So we would struggle between food-value and money-value to try and strike a good balance. Many times our food plan and menu turned out to be utterly useless. It was just not possible to cook it. We often miscalculated the time it would take lentils to cook. Then at night while washing a mountain of dishes we felt like wounded soldiers! Also the next day's cooked stared squarely in our face. But in the process of cooking for the community we learnt three very important lessons. These were elements of a nutritious and balanced diet, economics, and the art of cooking. I still remember that coriander green leaves have 10600 units of vitamin A. In just a few days I learnt many valuable lessons working in the community kitchen. Unfortunately, I did not learn any such valuable lessons in the entire decade I spent at the medical college. Experiments in AgricultureWhile in school, each child was allocated a small patch of land to grow vegetables. We had to plough, weed, water and grow stuff on our own. There would often be a long line of students at the well wanting to draw water to irrigate their crops. So, many children had to water their fields only at night. At night the wail of the jackals would frighten the children no end. But still they would gather courage to go and water their fields in the dead of night. By growing our own fruits and vegetables we leant the science of agronomy. Before applying any fertilizers we had to study their chemical compositions and for this we often went and had long chats with experienced farmers in our area. These included Mukteshwar Bhai who studied advanced paddy cultivation in Japan and Prem Bhai - a pioneer in cultivating grapes. Mr. Haveli's farm was just a stone's throw away. He had spent several years in Israel learning advanced agriculture. Often Mr. Anna Bhai Sahasrabuddhey would drop by and enlighten us on emerging techniques and economics of agriculture. In such a dynamic atmosphere we learnt a great deal about agriculture. There was a healthy competition amongst the students. We would vie with each to maximum the yield in our vegetable patch. To increase yields we would add a lot of fertilizers to our crops which essentially meant pouring bucketsful to cow urine. By adopting this novel technique I grew a brinjal with an astounding weight of 1.75-Kg. When I went to sell this super-sized brinjal in the Wardha market no one touched it with a long pole thinking it had some weird disease! Education for LifeThe Nai Taleem methodology is often accused of too much emphasis on manual labor, which becomes detrimental while acquiring knowledge. When Basic Education was introduced in the Madras Province people said, "A lot of time is wasted on manual labor, and so our children are lagging behind in their studies." Because of such accusations the then chief minister of Madras Rajaji had to resign. But what was the truth? People, who think children's minds should be cluttered with unrelated facts so that they could regurgitate them out in exams, must have certainly found some substance in this allegation. This group believed that if a child cannot list four different ways of making Sulfuric Acid then his knowledge base was weak. But how will this bunch of facts help a ninth grade child. They are totally unrelated to his life. The Nai Taleem students were found better than other children in every field of science which had a direct bearing with real life. But how did they fare in history, geography, political science and general knowledge when compared to the others? I never learnt geography at school in any formal way. Sevagram was full of visitors who came from many lands. I used to hear to their stories and from this I learnt a great deal about many countries. I was fond of collecting postage stamps and this gave me interesting information about different countries. I read many travelogues of foreign lands which gave me a good "feel" for these countries. This is how I learnt geography. In the ninth grade I read Sharatchand's "Pather Daavi" and Jhaverchand Meghani's novel "Prabhu Padhare". The graphic descriptions of these novels later inspired me to travel to Burma. For me the subject of geography was totally alive and kicking and not drab and boring. Our teachers taught us political science and general knowledge in a unique way. Every evening they would read us out important news items and interesting events from the newspapers. Later they would explain us the history and politics behind those events. One important new item at that time was America's retaliation to the weapons sent to Cuba by Russia. Then Second World War had broken out and the whole world was divided into two - capitalist and socialist camps. Our teachers would explain to us the reasons of mutual distrust between America and Russia and also the significance of the Cuban Revolution. Why Switzerland is called Helvetia? This question confronted me while collecting postal stamps. I read a number of books to find the answer and in the process I learnt a great deal about this beautiful country. New MethodologyOur school was the creative laboratory where several novel experiments were undertaken to implement Gandhiji's vision of education and Tagore's love for the arts. I will illustrate them with a few examples. Apart from the written exams we were also tested in our abilities to cook, write and playact, give lectures to a large audience and write articles. The novelty of the experiment was the flexibility inside the classroom. Every class has some clever and some not so clever students. Children did not have to appear for the same standard examination. This meant that in one single year I could simultaneously pass seventh grade English, ninth grade Mathematics and tenth grade Marathi. Inculcation of good values was an integral part of this education. As part of our daily school activities we lived these values and imbibed respect for manual labor, self-reliance, equality and working for the common good. Apart from these humane values, students also took part in struggles waged in the country for social transformation. For a few days the school was shut and all the students went away to far flung villages in Bihar to take part in the Bhoodan Movement. Whenever I recount these experiences of my old school people invariably ask, "Is that school still running? We too would like to send our children there." I would like to share one last detail about my school. Gandhiji's vision of village industries did not find favor with the Indian government. Soon small scale village industries couldn't compete and lost out to big conglomerates. Because my school had no government recognition it couldn't last long. In the absence of any recognition, the children's future hung in uncertainty. So, parents withdrew their children from the school. Many parents who actively participated in the Bhoodan Movement had admitted their children to this school. Later, they also withdrew their children. Our government and society both, failed to appreciate the value of this unique school. Under such hostile circumstances no island of change can survive for long. The harsh and barren social terrain outside the school, gobbled it up. Finally, the Bhoodan Movement also withered away. Deep rooted selfishness in society and the race to compete finally rang a death knell of this creative endeavor. I have a deep desire to send my son to such a school. But where is that magic school? |